Magazine Archive

Home -> Magazines -> Issues -> Articles in this issue -> View

Akai S900 Sampler | |

Article from Electronics & Music Maker, July 1986 | |

Akai's super-sampler carries on where their S612 left off. Paul Wiffen finds its ease of use belies its sophistication.

Akai's new S900 looks set to take 'affordable' sound-sampling into new realms of quality and sophistication. And above all, it's incredibly easy to use.

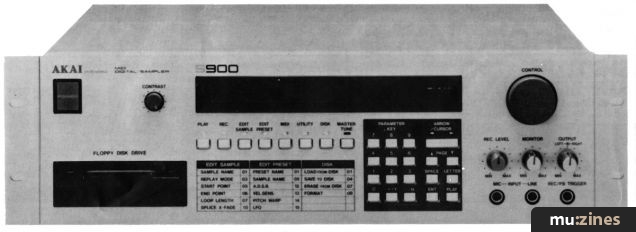

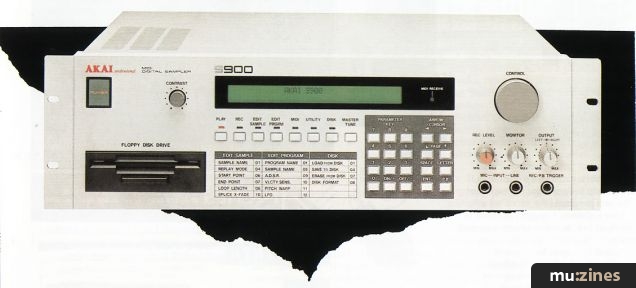

Of all the new samplers announced at January's Winter NAMM and Frankfurt shows, the Akai S900 is the first one to hit the market. The same company's S612 sampler is the basis of this new design, but a great deal of hardware expansion and software writing has taken place since the 612 appeared, and the result is a machine that continues the Akai tradition of rack-mounting modules, but adds another degree of sophistication altogether to what has gone before. The S900 samples for longer (maximum 63 seconds at low bandwidth), has a greater maximum bandwidth (16kHz), offers a wider variety of looping and editing options, and has a far more flexible MIDI implementation than its cheaper predecessor.

There are no compromises on ins and outs, with mic, line and trigger inputs, and mono, stereo and eight individual audio outputs, not to mention MIDI, RS232, and Akai's exclusive Voice Out system for external synth processing.

Perhaps most significant of all is the sheer user-friendliness of the new unit. It's the first thing that strikes you when you sit down to work with the machine. From the size and clarity of its back-lit liquid crystal display (with contrast knob to adjust for a variety of lighting conditions), to the logical ordering of the various 'screens' within each main mode, everything about the S900 underlines how easy it is to use.

As is the case with most of the new breed of 'affordable' samplers, if there's a disk in the drive when the unit is powered up, then it's automatically loaded up. Otherwise, the unit loads up a simple program called 'tone', based on a sinewave, which at least allows you to check that the unit is correctly connected. To load a disk from this situation (and at any other point in the machine's operation), you press the Disk switch. This calls up the mode in which you can access all the various disk operations, the first of which is - very conveniently - 'Load entire disk', followed by a prompt to push Ent (enter).

Provided you have a disk in the drive, it then begins to load. The LCD tells you the sample and program names as they are being loaded in, so you know what's going on. If you're loading a full disk the process takes about 40 seconds, but if the disk is only partially filled, it takes proportionately less time to load, which is a real advantage live.

Provided you have a MIDI keyboard (or guitar, or drum pad, or whatever) connected to the Akai's MIDI In, you can start playing the first program as soon as the disk has finished loading. If you switch to Play mode, the programs on that disk are listed in the display, with the currently selected one shown by a flashing cursor.

You can now select any of the available programs by pressing the appropriate number button. When you do this, the display does a kind of visual gymnastic, and the program you've selected is displayed in the centre of the screen. Presumably, this is so you can instantly see which program you are currently using. If you want to see the listing of all the programs available without actually calling them up (32 different programs are possible), then you can scroll through them all by using the rotary control knob; with a helpfulness that soon becomes par for the course, the display also tells you how to do this.

Pushing the numbered buttons isn't the only way of selecting programs. If it's easier (let's say the S900 is out of reach), you can use MIDI program changes instead. This means you simply select the patch number on your master keyboard or controlling synth, and this tells the S900 to select the program of that number. Again, this is especially handy for live use, but what worries me slightly is that there's no way you can switch off this response to program-change commands - so you need to be careful that patch changes on your MIDI controller don't conflict with what you want the S900 to be doing.

At this point, we'd better clear up exactly what the term 'program' means in Akai's book. It refers to a complete setup of the machine, usually containing several individual samples made up into one coherent 'instrument'. It's possible to have several different programs which share the same basic samples, but which are set up differently. This is particularly useful, as programs store not only samples and their arrangement, but also several other S900 functions - including MIDI and output assignments - independently for each program.

So, with just one program-change you can alter not only the samples being played, but also the MIDI channel(s) the S900 responds to and the audio outputs from which the samples emerge. We'll look more closely at the importance of this later on. By now, though, you're probably itching to know what sampling with the S900 is actually like.

As with all the functions, user-friendliness is the watchword in the REC (sampling) mode: the S900 guides you step by step through the sampling process. It does this by means of various pages which come up on the display. Seeing as sampling will probably be new to many Akai users, the S900 talks you through various stages of the process in great detail, stepping through a series of logically arranged pages that present the guidance you need in an easily accessible way. This is achieved by two buttons whose sole function is moving backwards and forwards through the pages. The pages are all numbered, and the key ones are listed on the Akai's front panel for quick reference.

And nowhere is the suitability of the scheme more aptly demonstrated than in Record mode. The order the pages come in actually provides a beginner's guide to the sampling procedure, as it takes you through the naming, monitoring, bandwidth, length, pitching and triggering of your sample-to-be.

Particularly worthy of note, I think, is Akai's decision to avoid confusion with sample rates and kilobytes of memory. They've done this by referring to the fidelity and length of samples in terms of audio bandwidth (in hertz) and time (in milliseconds) respectively. This means you don't need to bone up on sampling theory and divide sample memory by sampling rate to know how long your sound will last. Everything is presented in terms you can understand, without reference to too much sampling jargonese or maths.

Further evidence of this is the fact that the S900 is internally configured to make velocity switching or crossfading of samples really easy to do. Before you make your sample, the machine asks you whether you want to define your imminent sample as 'loud' (played when the key is struck hard), 'soft' (used for a gentle key-strike) or 'normal' (where only one sample is to be used for both hard and gentle key-strikes).

Of all the sampling systems I've ever used (across the whole price spectrum), this is the only one I'd confidently recommend to beginners in a hurry to make their own, sophisticated samples.

Guided by this idiot-proof sample set-up sequence, what results did I manage to come up with? I started with my usual acid test. Having set the audio bandwidth to maximum (16kHz) and sample time to the longest available at this fidelity (11.878 seconds), I connected a CD player to the line input on the front and proceeded to play it some loud, nasty rock music. The display was transformed into a left-to-right level meter for setting optimum level (good to see a large hardwired pot clearly labelled Rec Level on the front of the machine), and I was able to start the sampling process by hitting any button at random. If I'd preferred, though, I could have used a footswitch or the audio level to start the sampling. In the case of the latter option, the rotary control allows you to set a triggering threshold which the audio level has to pass before recording can start.

Once it had been recorded, all I had to do to hear it played back was hit Ent (as prompted by the display). Alternatively, pressing the Play button sounds the sample for as long as you hold it down. The 12 seconds' worth of music sounded more or less indistinguishable from its CD source to my ageing ears, and certainly the equal in fidelity of any other 12-bit system I have heard. In particular, transients (quick changes in level which often prove the most difficult thing for a sampler to cope with) were very faithfully reproduced.

So in sound quality terms, the S900 should satisfy the demands not only of musicians, but of studio engineers and producers, too. It may well find itself used for the type of production work that has until now been the exclusive territory of the likes of AMS machines: sampling drum sounds, backing vocals, orchestra hits, and other sonic mainstays of modern pop and rock music.

Going from the sublime to the ridiculous, I tried the longest possible sample that could be made by using the lowest available bandwidth (3kHz). The faster your sampling rate (which governs the fidelity), the quicker the available memory is used up and the shorter your sample has to be (you don't get anything for nothing in this world).

However, while the minute-plus' worth of recording I could get at this rate wouldn't win any prizes for quality, speech was still clear and comprehensible, and sound effects were recognisable if somewhat dull-sounding. Music recorded at this bandwidth was, of course, rather lacking in top end, but on reflection, the quality was little worse than that which so many of us put up with from our TVs.

The fact of the matter, though, is that you're unlikely to need the lowest bandwidth available, as the S900 has enough memory to cover the multi-sampling of most instruments quite comfortably at much higher quality.

It's also possible to adjust the audio fidelity very precisely, so you can use the exact bandwidth necessary to capture any sound and not be forced to use lower or higher fidelity simply because your machine can only manage one or two sampling rates. By offering a continuously variable sampling rate, the S900 makes the most economical use of the generous memory available, so you get the best of both worlds.

In fact, I soon discovered that 13-14kHz bandwidth was more than enough for most sounds, though there will always be more 'difficult' instruments (cymbals, high piano notes and the like) which need all the headroom they can get. My only grumble in this department is that there's no way the more experienced sampler (the user, not the instrument) can get an exact measurement of the sampling rate being used. If there was, you could match the sample frequency to a multiple of the pitch of a musical note for optimum fidelity.

Now, once you've made your sample there are all the facilities of the Edit Sample mode to play around with. Again, these are arranged in a logical order to guide you through the process of knocking your sample into shape.

The first page that comes up covers Selecting, Copying, Renaming and Deleting your sample, should any of these seem like a good idea. The second deals with how you access the sample on the keyboard (via any of the available programs).

Page 3 covers sample loudness and tuning. This enables you to match various samples to each other if they're of different levels or out of tune - vital if you want to make good multi-sampled programs of individual instruments over their full range.

Next, you can decide via Page 4 whether you want the sample to just sound once, to loop or to play backwards and forwards alternately. The first of these is the default, so a sample will play back as recorded unless you change it here. Page 5 allows you to reverse the sample so that it plays backwards. Well, it's easier than turning the tape over.

Looping is the way to extend a sample artificially, allowing the note to be played for as long as is required. But if you simply switch the loop on here, chances are you'll get a decidedly unmusical result, with clicking or gaps spoiling the sustain effect. Akai's manual quite rightly states that looping is 'an art and a science' and requires practice and skill to master. However, the S900 gives you all the help a computer can. Pages 6, 7 and 8 are where this happens.

Page 6 sets the Start Point of the sample and Page 7 deals with fixing the End Point. This allows you to specify just what section of the original recording you want to hear on playback, and is particularly handy if you were over-generous with the sampling time as a later page (9) allows you to Discard the data before Start and after End. This, in turn, means that any memory you don't need can be put back into the 'pool' of memory still available for new samples.

Loop Length is set on Page 8, and the loop uses the same End Point as the sample itself (set on the previous page). At first I was slightly worried about this, as I prefer to have independent start and end points for the loop, but I soon found myself adapting to this alternative approach. As things turned out, I discovered that ideal loops are often of virtually the same length, and that once I'd found a good loop, it was often possible to move it forwards in the sample without changing its length, thereby saving memory.

I managed to loop a lead guitar sample after only 0.3secs (when the original loop I found was around the two-second mark), all by shifting the sample End Point earlier.

On the negative side, though, it's not possible to have a sample stop looping and go through its natural release once you lift your finger off the connected keyboard. I guess each method of defining loops has its advantages, and until someone comes up with a system which combines the best of both worlds, it's a case of deciding which works best for you.

The Auto function on Page 8 offers computer assistance in fine-tuning your loops to get rid of clicking and glitching. As it seems to alter only the Loop Length rather than shifting the End Point, it can't work by finding zero crossings (ie. micro-seconds in the recording where no sound is present), and must therefore match points of equal sonic energy. Whatever the method, it worked as well as any other system I've tried, coming up with usable loops most of the time, producing the odd miracle here and there, and only occasionally failing to provide anything workable.

This, however, is the one area of sampling where you really do need visual editing for quick and completely glitch-free loops time after time. The Akai's RS232 port (which allows for faster sample transfer than MIDI can cope with) provides computer access to samples. Word has already reached us that Digidesign are at work converting their Macintosh Sound Designer package to run with the S900. We've also heard that Hybrid Arts are working on a sample editing package to run on the Atari STs, so it looks as though there'll be some choice available.

Once you've set your sample up, Page 9 allows you to Discard the portions of the sample you're not using, and also gives you the option of instantly Resampling at half bandwidth. Whilst this lowers the fidelity, it also halves the amount of memory used, which may be critical in some circumstances.

I found that, a lot of the time, you can get by with Resamples, though most musicians will no doubt prefer the higher fidelity whenever memory size allows.

The last three pages of Sample Edit mode deal with digital Splicing of samples. On the S900, this facility allows crossfade time and order to be specified or straight mixing to take place, and all this without losing your original pair of samples - just in case the splice doesn't come out as expected. However, it stands a better chance of being successful on the new Akai than on most machines, as crossfade gets around the glitching caused by matching the two adjoining levels. Quite why Akai didn't make this crossfade available for looping as well beats me, as the crossfade loops of something like the Sound Designer often allow you 'to loop the unloopable sample'.

Edit Preset is the largest of the S900's modes, with no fewer than 16 pages, most of which cope with an unlimited number of Keygroups (or keyboard splits) by giving a different display when each separate Keygroup is selected. Within this mode, you assign as many different splits as you need to spread your multisamples across the keyboard, and then edit their parameters either individually or all at once, whichever is more appropriate.

These include more complex functions like Positional and/or Velocity Crossfade and Switch (using the soft and loud samples we saw in Rec mode), and something called Warp (nothing to do with the Starship Enterprise, this - it means automatic pitch-bend, and it's great for brass), as well as more regular features like Filter (with keyboard tracking to get rid of aliasing effects), LFO (for vibrato with mod wheel or aftertouch control), ADSR (to reshape the loudness of samples) and velocity control routable to just about all of the above. And that was meant to be just a brief list...

Drawing attention to the most remarkable aspects of the Edit Preset Mode, one of these has to be the ability (unrivalled, I believe) to assign numerous samples to each note - I got as far as six and gave up trying. Then there's the fact that each area of the keyboard (essentially each sample) can be assigned not only to one of the eight mono outputs, but also to its own MIDI channel.

The only negative comment I can find to make on this aspect of the unit is that there's no separate ADSR for filtering, but then, you can always use that Voice Out socket to send samples to an Akai synth (the AX76, due out soon) for further analogue processing.

Moving to the MIDI section, we find that almost every eventuality has been covered, almost to the point of exhaustion.

Apart from the Mono Mode assignment of channels, the MIDI Mode and Base Channel are altered on Page 1. You need to turn Omni Mode off here to get the Mono Mode reception set up, of course. Page 2 allows you to specify a MIDI note number - complete with channel number and velocity level - to be sent from the MIDI Out when you hit the PB (playback) button, and also to test the S900's response to that note. Useful if you don't have your master keyboard to hand.

In contrast, Page 3 tells you the last note number received by the S900 at the MIDI In socket (again complete with channel and velocity data), regardless of whether the S900 actually played anything. This helps you decide whether your MIDI cable is at fault, or whether you're just using the wrong MIDI channel.

The last of the currently available modes (the Utilities package should arrive with the first software update) is called Disk. I've already covered the use of the conveniently-placed first page when loading a disk, and all the other disk functions are equally well positioned. You can Load and Save Samples or Programs either individually or together, and even erase on the disk itself. Whenever you insert a new disk, the S900 automatically loads the catalogue of what's on it.

Particularly praiseworthy is the way the Akai tells you the implications of your actions at every turn. For example, 'Clear disk and save entire memory' tells you that saving everything to disk will wipe out whatever was previously on that disk. Many musicians simply don't realise such hard facts of life until it's too late, and get caught out.

Continuing in this vein, even the Error Messages reassure you, rather than freak you out. No cryptic numbers or abbreviations here. All the messages are prefaced by a nice friendly 'Oops', and each one tells you exactly what's wrong and how to go about solving the problem. A good example of this is: 'Disk is write-protected. Take out of drive and close switch in bottom left-hand corner.'

DATAFILE

Number of samples 32

Number of programs 32

Maximum sample rate

40kHz = 16kHz audio bandwidth, 11.878 secs max

Minimum sample rate

7.5kHz = 3kHz audio bandwidth, 63.351 secs max

Sample memory 512K

Disk Drive 3½" double-sided

Analogue control (per voice) VCA with ADSR and VCF (both with velocity control), pitch mod via wheel, LFO (with desync) or warp

Digital control (edit sample) Start and End Points, Loop Length, Backwards, Splice (with crossfade); (edit program) Positional and Velocity Crossfade/Switch

Interfacing MIDI In, Out, Thru; Voice Out (exclusive); RS232 Standard Port

MIDI Modes Omni, Poly, Mono

MIDI note range 24 to 127 (C0 to G8) with velocity and aftertouch

Display 80-character back-lit LCD

Inputs Line, Mic, Trigger

Outputs Mix, Stereo Left and Right, 8 Individual Audio Outs

Price £1699

More from Akai (UK) Ltd, (Contact Details)

While on the subject of disks, it's worth briefly mentioning the three (excluding the blank one) that S900s are being shipped with. The first of these, described as an Operation Guide, provides various standard synth waveforms sampled and looped, and then goes on to show various multi-sampling setups with velocity crossfades and the like, using sampled spoken words such as 'Soft', 'Loud' and '1-2-3' to illustrate what's happening. Complete beginners could quite easily build their programs up from some of these, while a die-hard synthesist will appreciate a few old favourites as starting points to explore the machine's post-sampling facilities.

And just in case you weren't previously aware, Akai plan to make a separate operating system available on disk which will turn the S900 into an additive synthesiser via the generation of harmonics.

The Piano disk is as good as any that the competition in this price range is supplying, but the S900 is capable of much more. As usual, a bit of detuning covers a multitude of sins, making a presentable Honky-Tonk. The Chopper Bass is better, though, with some gutsy low end in normal playing on its own in one program, and a sharp top end in the pull-offs which are neatly selected by hard key-strikes on a second program.

Like every other new sampler, though, the S900 may suffer initially from the relative scarcity of library disks available for it. Akai are doing everything they can to improve the availability of library sounds, and my advice would be not to let the current situation deter you from giving this sampler serious consideration. The future should bring the sort of library disks you're after, as well as several new software-based applications like the additive synthesiser mentioned above, and a real-time event recorder.

As far as the current sampling software goes, it's unrivalled in the areas of program setup, MIDI functions and user-friendliness. And subsequent updates (like the Utilities mode) can only make things better.

All in all, the S900 is a combination of great spec, relatively low price, and appealing ease of use. Those factors in isolation would make it worth taking a serious look at, but in combination, they form a package that is almost irresistible.

Also featuring gear in this article

Akai S900 MIDI Digital Sampler

(IT Jul 86)

Akai S900 Revisited

(SOS Oct 87)

Akai S900 Sampler - SamplerCheck

(IM Jul 86)

Bits & Pieces - How To Upgrade Your Akai S900

(SOS Dec 88)

Eat your heart out PPG! - Akai S900 Sampler

(SOS Jul 86)

Getting The Most From... Mono Mode (Part 3)

(EMM Oct 86)

Sampling An Akai - Akai S900 Sampler

(HSR Sep 86)

Browse category: Sampler > Akai

Featuring related gear

Akai S950

(HSR Mar 89)

Akai S950 Digital Sampler

(MT Jan 89)

Browse category: Sampler > Akai

Browse category: Software: Sample Editor > Drumware

Browse category: Software: Sample Editor > Steinberg

Publisher: Electronics & Music Maker - Music Maker Publications (UK), Future Publishing.

The current copyright owner/s of this content may differ from the originally published copyright notice.

More details on copyright ownership...

Review by Paul Wiffen

Previous article in this issue:

Next article in this issue:

Help Support The Things You Love

mu:zines is the result of thousands of hours of effort, and will require many thousands more going forward to reach our goals of getting all this content online.

If you value this resource, you can support this project - it really helps!

Donations for November 2025

Issues donated this month: 0

New issues that have been donated or scanned for us this month.

Funds donated this month: £0.00

All donations and support are gratefully appreciated - thank you.

Magazines Needed - Can You Help?

Do you have any of these magazine issues?

If so, and you can donate, lend or scan them to help complete our archive, please get in touch via the Contribute page - thanks!