Magazine Archive

Home -> Magazines -> Issues -> Articles in this issue -> View

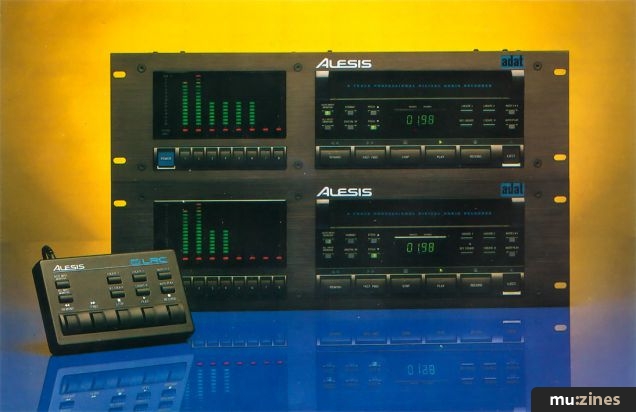

Alesis ADAT | |

8-Track Digital RecorderArticle from Recording Musician, September 1992 | |

It's finally here, it's available and it works!

It's been a long time coming, but it's finally arrived and looks set to seriously rock the home and semi-pro recording boat. Was ADAT worth the wait? David Mellor thinks so...

Once upon a time, having a home recording studio meant bouncing back and forth from one track to another on a stereo reel-to-reel tape recorder. It was a lot of fun at the time, but the generations of copying quickly built up and the quality of the end result was pretty dubious, to say the least. Now in my home studio I have a 16-track digital multitrack recorder, and I would only need to improve the standard of the acoustics and monitoring to have the technical capability to equal the sound quality achievable in the best studios in the world. Yes, this is progress, and it feels very good indeed. The 16-track digital multitrack in question comes in two boxes each the size, and something of the appearance, of a chunky VHS video recorder. In fact, the tape in each machine is a standard S-VHS tape of the type you can pick up quite easily in high street shops. Surely it can't be possible?

It's been a long wait since Alesis' first announcement of the ADAT 8-track digital multitrack recorder, but it has finally arrived and will be generally available very soon. I imagine that many are thinking "Why the delay?", and I wouldn't blame anyone for suspecting that Alesis have had difficulties in performing this not inconsiderable technical feat. These suspicions may extend to thinking that the finished model will be in some way less than perfect — an interesting proposition, rather than a practical tool for everyday use. As we shall see, the Alesis ADAT is a serious piece of equipment. Whatever delays Alesis had must have been due to their desire to make it as perfect as possible at its launch. Of course, no piece of equipment is absolutely perfect and the ADAT is no exception. There are certain points that could have been changed to improve the ease of use, but compared to the long list of problems that are inherent in analogue, these are mere trivia. Read on and learn about what is probably the most important development in cost-effective recording since Fostex introduced affordable 16-track...

First Impressions

The ADAT certainly makes quite an entrance as you carefully take it out of its packing. I have to admit, I was expecting something quite different. In my mind, Alesis are a company with great electronic and digital design capability but, since they have so far chosen to address the mass market with low-cost equipment, I had imagined that the ADAT would be fully functioning but not particularly robust. However, the ADAT is nothing like my expectations. It is admirably chunky, in a heavy-gauge steel case, and if you open it up you will see real build quality. Since affordable digital multitrack is a totally new concept, evidently Alesis want to make certain that it is taken seriously. My impressions of the look of the unit — visual design being important for ease of use — are neutral. In the lower echelons of pricing, manufacturers are sometimes reluctant to provide features like clear legending, large buttons and logical layout, for some reason I can't at all fathom. The ADAT is reasonably well designed from this point of view, but I really would have liked the Record button to be the traditional red, since even in the digital age it's the one button with which you can screw up a whole day's work. Also, my definition of the 'look' of a unit extends to the shape and feel of the controls, which should be as comfortable to operate as possible. The ADAT's transport controls are certainly large enough, but they take a lot of pressing and don't feel very positive. I didn't like the feel of the rubber buttons on the supplied LRC remote control either. These are small matters in light of the price, however.

Format

Alesis have made a very sensible decision to use an existing tape format, namely S-VHS. Tapes are easy to come by and are not likely to become outmoded for years to come. Like other rotary head digital recorders, ADAT works mechanically pretty much like a video recorder. The tape is wrapped around a head drum which carries, in this case, four heads. As the drum spins and the tape is carried past at a constant speed, the heads will trace out a pattern of diagonal tracks on the tape. This allows a very high relative speed between the head and the tape. Although it may seem like a marvellous feat to record eight tracks of digital audio onto a video tape in this way, the technology is already well established. The professional digital video format known as 'D2' records 8-bit samples onto tape at a sampling rate of 17.7MHz. Compare this to 16-bit digital audio sampled at 48kHz and work out how many digital audio tracks D2 could theoretically hold if re-designed for audio. Alesis are probably playing safe in recording just eight tracks onto S-VHS, which is a good thing, because the last thing we want is a format which is unreliable when not working at its peak fitness.

Alesis are keeping silent about the way the tracks are recorded onto tape. I would like to have been able to tell you, for instance, whether the tracks are recorded with a guard band between them, or whether the heads have different azimuth settings, as in DAT, which can cause problems due to narrow tracks being created at drop-ins. All I can say, however, is what I see with the top panel removed: the tape is wrapped approximately three quarters of the way around a drum just under 60mm in diameter, carrying four heads. There is a stationary head with two elements at the edges of the tape, which I assume are used for control tracks of some sort. The tape moves at three times the speed of a normal S-VHS recorder. The mechanism, by the way, appears very solid and well built. Compared to DAT, which most users will agree is far smaller than common sense ought to have allowed, this transport is heavy engineering. I can't give any guarantee of course, but it does certainly promise a high degree of reliability.

Setup And Recording

As I said earlier, I have the privilege of testing two ADATs, which means that my trusty Fostex E16 has been able to sit in a quiet corner for a while (I'm currently considering its future!).

One of the key features of ADAT is its inherent synchronisability (if there isn't such a word, then I've just invented it). Buy one ADAT and you have an 8-track system; buy two for 16, three for 24 and — counts up on his fingers — as many as 16 ADATs to make up a 128-track digital recorder. I wondered whether syncing ADATs would be as complex and bothersome as synchronisation usually is, but no — all I had to do was connect a 9-pin connector on one machine to a similar looking connector on the other. If I had more ADATs, I could have continued the chain. If anyone had told me that this would be all there is to it, I wouldn't have believed them, but it is and it works. In most synchronised systems, after a complex setting-up procedure, you have to worry about the slave catching up with the master all the time, and when you press the Play button you have to suffer several seconds of agony as the playback speed of the slave is slewed up and down to bring it into sync. With ADAT, you just plug in and go; the slave is virtually always in the same place as the master, so the time taken to lock up is usually three seconds or less, and the audio output from the slave is muted until lock-up is achieved. It's almost as good as having a single machine under your control. In fact, splitting the recording across two tapes can offer some advantages since you can, for instance, record as many takes of the vocal as you wish onto a third or fourth cassette before compiling them back together onto the master or slave reel.

Before making a recording it's best to format the tapes. You can record and format at the same time but I wouldn't really recommend this, except for live recording where you intend to use the whole tape in one go. Formatting is a simple operation and takes as long as the tape lasts — about 40 minutes for an S-VHS 120 cassette; you can stripe timecode at the same time, if you wish.

As far as recording and playback go, the ADAT is just like a conventional multitrack recorder, but differences arise in the wind modes. As with most rotary head recorders, there are two ways in which the tape can be fast wound. The quickest way of shifting tape (20 times play speed) is to wind it back into the cassette first, although the threading and re-threading procedure takes a little time. Alternatively, the tape can be left wrapped around the head drum so winding is slower, because the tape path is more complex (10 times play speed). The advantage of this is that winding can start immediately. I would recommend making full use of the autolocate facility, which has three memories. Since the machine knows from the current position how far it has to travel to the locate position, it will choose the most appropriate wind mode for you.

ADAT In Use

The one way to find out whether a piece of equipment really works is to use it on a practical project. I spent two days using it in place of my analogue multitrack on a project which I eventually intend mastering for CD. As far as sound quality goes, I was quite happy that the ADAT was the equal of my Sony DTC1000ES DAT which, although it isn't indistinguishable from the live sound, is a million times better, in my opinion, than any analogue recorder ever made. When you're setting levels with the ADAT, you do have to bear in mind that when the meter shows red it really does mean that you have gone too far. A check with a sine wave tone produced some very interesting whooshes and wails. While I had my sine wave generator connected, I tried some drop-in tests. Yes, drop in and out are both gapless and clickless, although you will hear a click in the monitor as you do it. Crossfading at the join is very smooth and you can drop in and out undetectably almost anywhere in real music. I wondered whether repeated drop-ins at the same point would be a problem but I didn't find that it was.

Operating two machines synchronised together proved only a very slight inconvenience. Apart from the record-ready switching, everything can be controlled from the master machine or the supplied LRC remote control (and a drop-in footswitch for DIY enthusiasts). The quality of sync is absolute: I tried some things you would never do on machines synchronised using SMPTE timecode, and the result was perfect. You really can split a stereo track across two machines without any problems at all. I did find that the slave machine occasionally got confused about where it was supposed to be, which meant a delay in lock-up next time entered play, but this didn't happen often enough to be really annoying. More annoying is what can happen when using the fast cue function, on the LRC remote control, by holding Play and Wind simultaneously. If one finger happens to leave the Play button a tiny fraction sooner than the other leaves Fast Forward or Rewind, then the tape will go into wind mode proper — you think you've found the spot you want and then the tape shoots off into the distance.

The other thing I found annoying concerns the autolocation functions. There are three locate positions: 0, 1 and 2. You can cycle between 1 and 2 and also select an Autoplay function, whereby the machine goes into play mode when it reaches the locate position. I found that the response of the Cycle and Autoplay buttons could be very slow, depending on what the machine was doing at the time, and I often thought that the button hadn't registered and so pressed it again — with the end result that I cancelled the operation had selected. Alesis should find a way to make the operation, or at least the LED indication, of all of the buttons immediate so that the user receives the appropriate feedback, and knows that the ADAT will do what you have asked it to do and that it's not ignoring your demands.

Doubt No More

Cynics are bound to be thinking that there must at least be something wrong with the ADAT — apart from stiff transport controls and a couple of slow-to-react autolocate buttons — but really there isn't. Affordable digital multitrack is here and it works. OK, I did find one thing, but I doubt whether you are going to come to grief over it. A pair of ADATs have the facility to clone any or all tracks on a tape digitally onto another tape (great for backups). The clone can be given the same sync reference as the original, so if it was part of a master-slave pair and you cloned all eight tracks, it should be totally interchangeable with the original tape. In fact, the digital clone will play back approximately 20 microseconds later than the original — I spotted this accidentally and did a rule of thumb measurement on my oscilloscope. If you did, by chance, split up a stereo pair of tracks by cloning one of them and then mixed them into mono, you might notice a loss of very high frequencies, but this would be a very unlikely chain of events. With all normal copying and track bouncing operations everything else is perfect (and a 20 microsecond discrepancy is in fact within Alesis' claim of single sample synchronisation accuracy).

Although I have no way of knowing for sure how well the Alesis ADAT will stand up to the rigours of studio use, I feel confident in saying that future musicians and engineers will look upon it as a milestone in audio development. It's not the first digital multitrack, and it certainly won't be the last, but it's the first one the ordinary person in the home or small studio can seriously consider owning. High-end professional digital multitrack users will also be keeping an eye on this development. It's unlikely that anyone will be throwing away their DASH or ProDigi reel-to-reel multitracks, because they are both proven formats with a very strong user base. But just as we now have an alternative to a Tascam or Fostex analogue multitrack in the small studio, ADAT is showing the Sonys, Mitsubishis, and Otaris of this world that there is another way of doing things. Well done Alesis.

Kiss Your Analogue Problems Goodbye

REEL SCRAPE

Newcomers to the recording studio find this noise intensely annoying, although many engineers seem to be able to filter it out somewhere along the connection between the ear and the brain. No matter how well aligned your machine, no matter how flat the flanges of the spool, no matter how carefully you thread the tape, that irritating rasping sound comes back again and again. If you try to correct the problem by bending the flanges of the spool you'll only make it worse, and you may be tempted to adopt the solution many continental Europeans do, which is to use spools without an upper flange. Be warned, however, that you have to use European tape if you take a screwdriver to your empty take-up spool, because the American stuff will throw its coils skywards when you fast wind.

NOISE

Think of all the trouble you take to lay a nice clean signal down onto tape, and then consider what happens when it is deposited on the rusty metal particles of the tape's magnetic coating. The result is that your lovely music plays back mixed with a random signal, which is commonly known as 'tape hiss'. Tape is a noisy medium, an order of magnitude noisier than high quality audio electronics, and tape, rather than any other component of the recording chain, has set the limit on our achievements ever since it was invented. Things have improved vastly over the years, particularly with the various forms of Dolby noise reduction, but when you hear background noise on your finished recording, you can be sure that most of it is coming from the analogue multitrack recorder. Digital recording doesn't eliminate noise; a digital multitrack recorder should really have a resolution of at least 18 bits to bring the finished mix up to full CD standard, since noise build-up is inherent in any multitrack recording process, but the 16-bit ADAT provides a very noticeable improvement on what most of us are used to.

MODULATION NOISE

Tape hiss is one kind of noise, and is due to the fact that the signal is recorded on particles of finite size. Modulation noise is something else, and is arguably more annoying — noise that rises and falls in level with the level of the signal. Modulation noise makes a recording sound 'dirty', and is particularly noticeable if you are recording without the benefit of Dolby noise reduction. If you use dbx noise reduction, this has the effect (through a different mechanism) of making the modulation noise worse. Digital recording isn't totally free of modulation noise, but at 16-bit resolution you would be quite hard pressed to hear any.

PRINT-THROUGH

You have just made a technically perfect recording of a piece of music with true beauty and meaning. You take the tape off the machine and put it carefully on the shelf ready for mixing tomorrow. Tomorrow comes and you play the tape — it isn't at all like you remember it. All the loud percussive sounds have strange echoes, not only after the initial sound but also before it. This is print-through. Particularly during the first 24 hours after a recording is made, the magnetic force of each loud sound will seep through perhaps two or three layers of tape in both directions, causing pre- and post-echoes. Other than fast winding the tape a couple of times in each direction (which doesn't make very much improvement), there is no safe cure for print-through. It has messed up your recording forever. Two methods of reducing the effects of print-through are to use noise reduction and to store the tape tail out. Although there will physically be print-through on a digital tape, it won't affect playback in the slightest. Score so far: Digital 4, Analogue 0.

HEAD ALIGNMENT

All analogue recorders are aligned so that the gaps of the record and playback heads are precisely at 90 degrees to the direction of tape travel. If this statement were true, then head alignment wouldn't be a problem. In practice recordings are made on machines with wrongly aligned heads, which then will not play correctly on a properly aligned recorder. This causes a loss of high frequencies and has a damaging effect on the stereo image.

Although the alignment of digital heads is important, a small deviation wouldn't make any difference at all to the sound, and since the head alignment isn't user adjustable, no one can get it wrong — apart from the manufacturers, who really ought to know what they are doing!

GAP SCATTER

Even if the heads of a multitrack recorder are aligned as well as it is possible to align them, there is still the manufacturing defect known as 'gap scatter'. This is when the gaps of the individual record or playback elements of the head are not all at exactly the same angle. This makes it impossible to align the head properly for all the tracks. In rotary head recorders of all types, including ADAT, there can be no gap scatter.

LINE-UP

Analogue recorders are very moody. Their performance changes with the state of wear, type of tape, the weather, and any one of innumerable variables. An essential task involved in operating an analogue recorder is line-up. At the small studio level, line-up will be performed rarely but (hopefully) regularly. Major studios consider line-up as important as tuning a piano. You wouldn't be happy if you were paying several hundred pounds for a day in the studio and found that the piano was out of tune. You also wouldn't be happy if the recorders were not working at the peak of their performance. Digital recorders do need lining up, but this is a job for specialist engineers and, as long as they are running within specifications, the tape will record and play back perfectly.

WOW & FLUTTER

There is no such thing as a perfectly flat surface, a perfectly round shaft, or a perfectly spherical ball bearing. It's also impossible to align two cylinders so that they are perfectly concentric. The result of this is that the tape machine that runs at an absolutely steady speed will never exist. In the analogue world, this matters because tape speed has a direct bearing on pitch. Slow variations in speed cause wow, faster ones cause flutter. A digital machine will not run at a perfectly constant speed either, but since the data can be read into a buffer memory and then be clocked out with the accuracy of a crystal oscillator, it doesn't matter at all if the mechanics are slightly wobbly (within specification, of course).

TIMECODE PROBLEMS

Timecode is to recording engineers what spots (zits) are to teenagers, and sometimes we forget that, unlike spots, timecode does indeed have a few benefits. But when your synchroniser won't synchronise, or your sequencer drops out of record at the wrong moment, you will be snarling and cursing and wondering why you didn't take up a career as an interior decorator. If you have ever looked at raw timecode on an oscilloscope, straight from the tape machine, then you won't be at all surprised that you get the occasional troublesome moment. In fact, if you look at a steady 1 kHz sine wave replayed from tape, you will be amazed that recordings of music sound anything like the real thing! Even on a good tape recorder the sine wave will be bobbing up and down like a dinghy crossing the wake of the Isle Of Wight ferry — and make that the QE2 when the head gets worn. But if your timecode is recorded onto digital tape, as described in the main text, then it will be absolutely rock solid and almost as dean as when it was fresh out of the generator. The low-cost timecode readers usually found associated with MIDI sequencers will particularly appreciate this.

EDGE TRACKS

What did your mother tell you when you were small? Never record important parts on the edge tracks! Of course we all know this, but the problem is that we don't always know how a piece of music is going to develop. Sooner or later, when all the tracks are full, the producer is bound to say, "Let's ditch the castanets (which are on track 1) and put down this important vocal counterpoint I've just thought of." Or words to that effect. If you use an analogue multitrack I'll ask you the question, "How good are your edge tracks?" Try recording stereo music on tracks 1 and 2 and play back on headphones. If your heads are at all worn, you will hear image shift and dropouts on track 1. Since ADAT is a rotary head recorder, it can't be said to have an edge track in the normal sense, so you can be sure that each track will have identical performance within infinitesimally small margins.

DROP-OUT GAP

So your guitarist needs 100 takes to get his solo correct. It shouldn't be a problem as long as you can drop him in at the right points to fix dodgy notes. Dropping in is easy enough, and analogue recorders have carefully-timed erase current ramping so that the changeover will be almost perfect. Dropping out is another matter, however. It is possible to drop in almost at any point, as long as your timing is good, but dropping out always produces a glitch in the recording, so you have to drop out on a gap in the music. If there isn't a gap, then you're in trouble. On the ADAT, dropping in and dropping out are both gap-free. If you try it on a 1 kHz sine wave (which is the ultimate test), you'll hear a short crossfade on entry and exit. On music, you are very unlikely to hear it at all.

CROSSTALK

In any analogue equipment there will always be crosstalk, which is defined as a signal leaking from a path where it is wanted to a path where it is unwanted. This is a terrible nuisance, especially in multitrack recording when, let's say, a loud snare drum beat leaks onto the vocal track. The crosstalk will be an inconvenience until you decide that the song doesn't need that snare drum after ail — even when you erase it, it will still be clearly audible on the vocal track, and it becomes a major problem. Digital multitracks cannot be totally free of crosstalk either, because there are still analogue signals within the equipment, but there is no crossover from one track to another, which is a major benefit (except that you will soon become dissatisfied with the crosstalk performance of your mixer!).

RECORD CROSSTALK

This is a different manifestation of the crosstalk phenomenon. During overdubbing on a multitrack recorder, you are asking one element of the head to play back while another is recording. The recording element will be carrying a large current, while the playback element will be producing only a very tiny one. You will notice the effects of record crosstalk when you record on the track adjacent to the hi-hat. As you record and monitor the signals from the multitrack, you will notice that the hi-hat has suddenly become much louder and much brighter. If you solo the track you are recording on, you will be able to hear it quite clearly, as the result of record crosstalk. It won't be there when you play back (apart from the normal amount of track-to-track crosstalk you would expect), but it's a pain when you're recording. You may also notice that other tracks seem to jump up and down in level, corresponding to the rhythm of the track, while you are recording. This is a result of the record crosstalk sending false signals to the noise reduction system. Once again, it won't happen on playback — but on a digital multitrack it doesn't happen at all.

HEAD FEEDBACK

Related to and caused by the above, this happens when you try to bounce a signal onto the adjacent track, as you might if you were compiling vocal harmonies onto a single track. Unless you are careful with the level, you will obtain a high pitched whistle (potentially speaker blowing) which is caused by feedback within the head. Once again, it doesn't happen with a digital multitrack.

NOISE REDUCTION PROBLEMS

Noise reduction systems are great, but they are not perfect, and even if they can fool the ears of most of the people for most of the time, experienced engineers will still be able to hear their artifacts. Sixteen-bit linear digital recording uses 'brute force' techniques to give a dean, quiet recording without any psychoacoustic trickery.

HIGH FREQUENCY SQUASH

Analogue tape isn't very keen on recording high frequencies. As you try to put more level onto tape, high frequencies become distorted before mid and low frequencies, which most people would say is not a good thing — although it does contribute to the analogue 'sound', which is liked by some. Digital recording treats all frequencies equally, so your lows, mids and highs will ail be equally clean.

THREADING & RUN-OFF

Yes, there are reel-to-reel digital recorders but, eventually, all recorders will use cassettes of some type. We thread tape now because we have to. In a few years time, we'll think of it as something from the dark ages as we feed another cassette into the slot. And how much session time is wasted in re-threading tape that has accidentally spun off the reel? There are ways and means of avoiding this, but they also take up time. It'll never happen on an ADAT.

COUNTER SLIPPAGE

"Let's go back to the beginning of the first verse", says the producer; you press the appropriate locate button, which you had thoughtfully pre-programmed. Unfortunately, this was some time ago, and with all the shuttling of tape that has gone on, the counter has shifted and the tape comes in halfway through the first line. This may seem a minor point, but many minor errors in location add up to a lot of wasted time. If the tape has a time reference recorded on it, then location can be bar-accurate every time. You can use timecode on an analogue tape for this purpose, with the correct equipment, but a digital format can have this built in. ADAT has.

CLEANING?

Yes, cleaning analogue recorders is a chore but it has to be done, otherwise your recordings suffer. Cassette-based digital recorders are a fairly new invention, so there isn't a lot of data available, but it seems that we are going to have to consider what cleaning routines are necessary. I used my DAT machine for around three years, with regular applications of a cleaning cassette, before it developed a transport problem. I opened it up and oxide was caked around the pinch roller and on several of the guides, so obviously the cleaning cassette is only a partial solution. There is no advice in the ADAT manual other than to clean the external surfaces with a damp cloth, but I suspect that this is one area where digital multitracks will not have an advantage over analogue — we'll still have to keep them clean.

PHASE DISTORTION

If you throw a bundle of different frequencies (which could be music) at a piece of equipment, you hope that it will throw them back at you with the lows, mids, and highs all in the same proportion. If it does, then we say it has a good frequency response. One might also hope that they would all come back with the same relative timings, but in practice the lows or highs may be advanced or delayed with respect to the mid frequencies. If this happens more than the minimum amount that corresponds with the frequency response of the equipment (frequency and phase response are closely linked) then there is phase distortion. Analogue tape recorders are the worst offenders in this respect. Try recording a square wave and view it on an oscilloscope — it will come back anything but square. It used to be thought that this doesn't matter, since it still sounds pretty much, in fact almost exactly, like a square wave. But almost isn't good enough, and the phase response of digital recorders is much, much better.

DROPOUTS

Analogue tape and digital tape can both suffer from dropouts due to faults in the tape. The difference is that with analogue the effects can be unnoticeable, irritating, annoying or disastrous, depending on the dropout's length and depth. A digital system can be designed so that its error correction system can cover up faultlessly the worst dropouts that can be expected in everyday use. However, really bad dropouts will cause the system to mute — even if the muting can be switched off, there may be a loud digital 'splat'. Some would argue that the advantage here is in analogue's favour, since you will get at least something from the tape and dropouts never cause additional noises.

ANALOGUE ADVANTAGES

It wouldn't be fair not to mention a couple of things that analogue can do that digital can't. Spot erasing a click in a digital recording can be impossible, difficult, or time-consuming, depending on the system. On an analogue recorder with a specific spot erase facility, it's straightforward enough. Even if the recorder lacks such a facility, it may be possible to do it by rethreading the tape so that it doesn't pass between the capstan and pinch roller and then moving the tape by hand. Another analogue trick which used to be very popular before we had such an array of effects units is to turn the tape over and record backwards — even now, it's the only way to create true reverse reverb.

Which Track for Timecode?

Suppose your master ADAT is connected to tape outputs and inputs 1-8 and the slave is connected to 9-16. If you record timecode on track 16, then the slave will take three seconds or more to start after the master enters play or record and only then can your sequencer attempt to lock up, so timecode really has to be recorded on the master. It doesn't matter which track you use, but you are now going to have to work around the 'hole' on your mixing console, which is irritating. The alternative would be to connect the slave to 1-8 and the master to 9-16, but I can't help feeling that this is thoroughly illogical. As the price of progress, I'm sure we'll get used to it.

BRC — the Big Remote Control

- You lose an audio track for timecode.

- There's no provision for digital synchronisation to other equipment (which one day soon will be very important, mark my words).

- There are no record-ready switches on the remote control.

- Only three locate points are offered.

- No editing is possible...

- Its buttons are not very positive.

Alesis are not saying very much about their plans at the moment, but I suspect that, at the very least, the first five points will be answered by the BRC.

Professional Applications?

Tape Wear

Multitrack recording usually involves going over the same sections of a piece of music again and again; by the end of the session, the tape may have passed the heads hundreds of times, so there is the distinct possibility of error rates creeping up. The ADAT won't cycle automatically for more than half an hour, so my intended overnight cycling test didn't work. I thought the next best thing would be to take a five year-old standard VHS tape, which has been re-used many times in my video, and record audio on it. It certainly isn't recommended to use anything less than the best tape, but I have to say it sounded absolutely perfect!

Other ADAT Accessories

Designed to mount above the BRC remote control. Provides 32 channels of LED meters.

AI-1 INTERFACE

The ADAT has only a proprietary 8-channel optical digital input and output. The AI-1 will be able to translate this to AES/EBU (professional) and S/PDIF (domestic) digital formats. Apparently, this will also include a sample rate convertor.

AI-2 ESBUS INTERFACE

One of the unfulfilled dreams of professional audio is that all equipment should have a standard synchroniser interface. ESbus is such a standard, defined by the EBU and SMPTE, but it hasn't made as much progress with manufacturers as it should. Full marks to Alesis for supporting it.

ADAT Specifications

| Recording format: | ADAT (Alesis Digital Audio Tape) |

| Recording time: | 40 minutes with S-VHS 120 cassette |

| Fast wind speed: | 20x play speed with tape unwrapped |

| 10x play speed with tape wrapped | |

| Fast audio scan speed: | 3x play speed |

| A/D conversion: | 16 bit linear, Delta-Sigma 64 times oversampling, single convertor per channel. |

| Sample rate: | 48kHz (varispeed 40.4 to 50.8kHz, +1, -3 semitones) |

| Frequency response: | 20Hz to 20kHz +/-0.5dB |

| Dynamic range: | > 92dB from 20Hz to 20kHz, A-weighted |

| Distortion: | 0.009% THD + noise @ 1 kHz, 0.5dB below maximum output, A-weighted |

| Channel crosstalk: | < -90dB @ 1kHz |

| Wow and Flutter: | Unmeasurable |

| Connectors: | 56-pin ELCO |

| 16 quarter-inch jacks (8 input, 8 output) | |

| 2 EIAJ fibre optic (1 input, 1 output), Alesis Fibreoptic Multichannel protocol |

Also featuring gear in this article

Alesis ADAT - 8 -Track Digital Recorder

(SOS Sep 92)

Alesis ADAT Digital Recorder

(MT Sep 92)

Browse category: Digital Tape Deck (Multitrack) > Alesis

Featuring related gear

J.L Cooper DataSync

(SOS Oct 93)

Browse category: Synchroniser > JL Cooper

Browse category: Remote Control > Alesis

Publisher: Recording Musician - SOS Publications Ltd.

The contents of this magazine are re-published here with the kind permission of SOS Publications Ltd.

The current copyright owner/s of this content may differ from the originally published copyright notice.

More details on copyright ownership...

Gear in this article:

Review by David Mellor

Help Support The Things You Love

mu:zines is the result of thousands of hours of effort, and will require many thousands more going forward to reach our goals of getting all this content online.

If you value this resource, you can support this project - it really helps!

Donations for April 2024

Issues donated this month: 0

New issues that have been donated or scanned for us this month.

Funds donated this month: £7.00

All donations and support are gratefully appreciated - thank you.

Magazines Needed - Can You Help?

Do you have any of these magazine issues?

If so, and you can donate, lend or scan them to help complete our archive, please get in touch via the Contribute page - thanks!