Magazine Archive

Home -> Magazines -> Issues -> Articles in this issue -> View

Arms and The Man | |

Dire StraightsArticle from International Musician & Recording World, January 1986 | |

A fly on the wall account of a mega-group amidst a mega-tour. Michael Smolen does the buzzing

Straits, Strats, Strings, Singles, Success, Sidemen, Steinbergers, Superstars, Sellout Shows, Stadiums, Sultans of Swing, and Secrets. Mark Knopfler and his band Dire Straits pause stageside Stateside to share some stories.

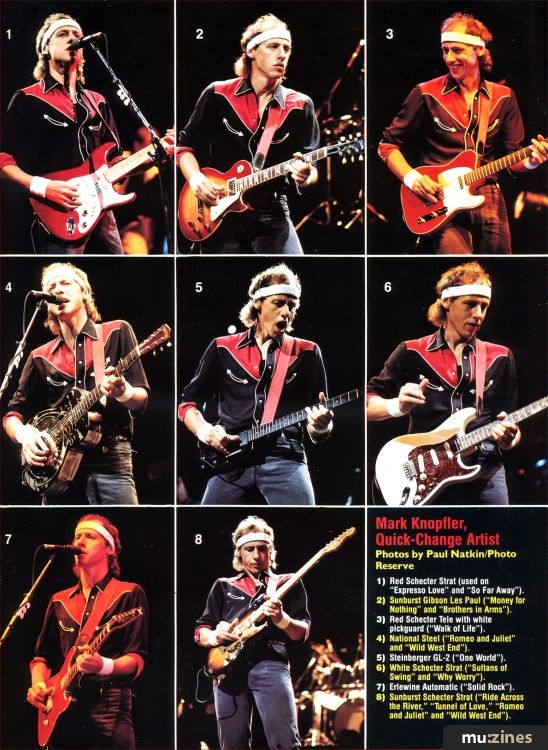

Mark Knopfler, Quick-Change Artist

1) Red Schecter Strat (used on "Expresso Love" and "So Far Away").

2) Sunburst Gibson Les Paul ("Money for Nothing" and "Brothers in Arms").

3) Red Schecter Tele with white pickguard ("Walk of Life").

4) National Steel ("Romeo and Juliet" and "Wild West End").

5) Steinberger GL-2 ("One World").

6) White Schecter Strat ("Sultans of Swing" and "Why Worry").

7) Erlewine Automatic ("Solid Rock").

8) Sunburst Schecter Strat ("Ride Across the River," "Tunnel of Love," "Romeo and Juliet" and "Wild West End").

Image credit: Paul Natkin / Photo Reserve

'That ain't working, that's the way you do it. Money for nothin' and your chicks for free.' Oh my God! A 36-year-old guitarist aspiring to an idealised Rock and Roll lifestyle? Surely not. Especially not when that particular 36-year-old guitarist happens to be Mark Knopfler, a man who's toured the world playing Rock, Rock and Roll, or whatever you want to call it, in much the same way that an albatross tours the Pacific.

In fact on this particular day in an Ottawa hockey stadium, in the middle of a lengthy US tour, the uneventful and uninspiring scene is one that must come as no surprise to Knopfler. A hiatus has occurred. Confusion has resulted in a standstill, so that crewmen are now sitting round a jar of pickled jalapenos and dipping into the beer cooler, with seemingly little concern for the concert due to take place in the evening, let alone an imminent soundcheck. Someone's got to get this show moving again, and that will mean sweat and hassle all round. So what exactly does the Rock star mean?

"I was in this store in New York," explains Mark Knopfler, "that had a wall of TVs at the back, and rows and rows of refrigerators, microwaves and all kind of appliances. In the back all the TVs were tuned into MTV (the US round the clock music video channel) and this guy was sitting there mouthing off in the most classic fashion. I snuck behind this guy and watched him from behind some microwaves, trying to remember all the things he was saying. He had what the Americans call a 'Hard-hat mentality.'

"It was so funny," continues an uncharacteristically animated Knopfler, "I went up to the front of the store and asked somebody for a pen and paper, and I actually sat down in the front window and began to write the lyrics for Money For Nothing."

Back in Ottawa, those lyrics are beginning to take on some real meaning. The Dire Straits entourage — Knopfler, bassist John Illsley, ex-Rockpile drummer Terry Williams, guitarist Jack Sonni, sax/flute/percussionist Chris White, and keysmen Alan Clark and Guy Fletcher — have arrived for soundcheck. Sonni is stopped by a local fan: "So, you're gonna have a good show tonight, eh?"

[Deadpan] "Nah, we're not going to play well tonight."

"No, c'mon, eh! You're gonna do a good one."

[Still deadpan] "No, really, none of us feels well; we're not going to do a good show tonight."

"Ah, no, you're kidding, eh?"

There is still time for humour here, though not much. Tour manager Paul Cummins whisks in, and suddenly the Straits road crew looks very busy.

A band meeting is called in the dressing room, and bodies rapidly disappear from the makeshift cafeteria area, leaving behind the woman who did the catering for the show and two scantily clad groupies. For a moment things are quiet. Then, one by one, members of the crew begin to emerge from the dressing room, their faces something out of Night of the Living Dead. Comments range from "Man, I hadda get out of there," to "Don't go in there, you'll get eaten alive!" Somebody — a good bet would be the perfectionist Knopfler — is obviously rather unhappy with the way things are going, or last night's show, or both.

"There's only one way to get someone to understand all that goes into this gig," contends Knopfler. "And that would be not to just have him come to the show, but to have him come to soundcheck every day, have him stay with me all the time. Even then he would have no concept of what it means to go through months of recording, months of rehearsals, hundreds of hours of writing, dealing with a band, organising a tour, doing videos, doing interviews — it's such a long cycle, so much is involved in this thing. Even so, I didn't hate that guy in the store just because he was a prejudiced blockhead; I loved him even though he represented everything I can't stand."

Dire Straits' present global assault is scheduled for over 220 dates, and there's talk of even more being added. It's been estimated that the two-and-a-half-hour show costs in excess of $22,000 per day to put on and requires a crew of over 60 people. Things often don't go quite so smoothly. Backstage, small scenes begin to unfold, such as finding out that the two phones installed for band use both operate on the same line — a shouting match tells you one is not enough. A sigh is heard, a $50 piano-tuning bill is sighted, and on the bottom in red ink is a $15 additional charge for "waiting time."

"The road is great, though you really have to love it, you really have to be into it," says Knopfler, who's toured regularly with Dire Straits since the band exploded internationally with Sultans of Swing in 1979. "Sure, some of the lows are pretty low, but they're not worth talking about because this band is so fabulous. We had trouble with the keyboards for a while, but Guy Fletcher and the crew are so together that things are fine now. I don't think this show has been as difficult to put together as the last one, which was pretty damn big."

Knopfler's enthusiasm for the road, however, may be dwindling. "I think this is the last of the big shows for us," he admits. "We just did two weeks at Wembley Arena in London, and it's gotten to the point where you say, 'Well, I've done that.' Our promoter told me I could have done a month there, but you have to be crazy to do two weeks there anyway. So given the fact that we're already crazy, I don't see any reason to repeat it. Anything we do in the future is going to be much smaller; we'll do away with these massive PAs and lighting systems. I think that by the end of this tour I'll be more interested in playing small places and doing a different kind of thing altogether — if I go back to playing live."

The scope of Dire Straits' live show begins to take place at soundcheck. Needless to say, Ottawa's Civic Center was built for hockey, and for some unknown reason the oval arena has been bisected horizontally instead of vertically for the stage, losing a good many seats for a sold out show. Knopfler strolls on stage and is handed his favourite red Schecter Stratocaster, Illsley straps on his '61 Fender Jazz bass, and Terry Williams parks himself behind a massive Ludwig/Simmons/Paiste drum kit. Fletcher and Clark are busy tuning oscillators. The PA is fired up, and the empty arena comes alive with various bits and pieces of the set.

Second guitarist Jack Sonni, wiry, curly haired and sporting a loud Hawaiian shirt, bounds onto the stage and is handed his prize seafoam-green Schecter Stratocaster, and almost immediately the mood on stage changes. A recent addition to the band, in place of Hal Lindes, he radiates enough energy for both the entire group and crew. Knopfler cracks a rare smile and is handed his Gibson Les Paul Standard for a run-through of Money for Nothing.

"I use the Les Paul for different things," explains Knopfler, who is rarely seen sans Schecter Strat. "I think in terms of the Les Paul and string sounds. That always sounds nice to me. The Gibson, if played in a certain way, can sound really great with other instruments. I find that with my style of playing, however, I have to mask out certain strings to stop certain sounds. You get so much more sound from the Les Paul, you have to be careful that you're not bashing away on the wrong strings with your neck hand. For example, when I do the intro to Brothers in Arms I sort of mask out certain strings so that they don't make any noise."

Image credit: Paul Natkin / Photo Reserve

Perhaps the single most important aspect of Knopfler's technique is his attack on the strings. He eschewed the use of a plectrum a long time ago — "while learning to play everything from Blind Blake to ragtime to country blues and Western swing" — in favour of fingerpicking, upstroking with the middle, index and ring fingers of his right hand and downstroking with his thumb. Occasionally, he will pluck or snap a string for an extra-decisive pop on a note. This style is known to some as the claw-hammer.

"I realise there are a lot of things you really need a pick for: quick single-note lines and all of that blazing stuff," says the sultan of Strat. "I really should be using a pick, but I don't. I like the direct feel of playing without it. I like to sort of squeeze out the music with my bare hands."

Knopfler squeezes out quite a storm when he plays and does so with a tremendous variety of equipment, using a different guitar for practically every song. His current options include four Schecter Stratocasters, two Schecter Telecasters, the aforementioned Gibson Les Paul Standard, an Adamas acoustic, a National Steel, an Erlewine Automatic and a Gibson Chet Atkins. A recent addition to Knopfler's guitar collection is a Steinberger GL-2. He uses MESA/Boogie and Jim Kelley amplifiers played through Marshall 4-12" cabinets loaded with Electro-Voice drivers. His rack and his Peter Cornish custom pedalboard house a Roland SRE-555 chorus/echo, a DeltaLab digital delay, a Mic-Mix Dyna-Flanger, a Master Room reverb unit, a Roland graphic Eq, an Ibanez UE-303 multi-effects unit and a variety of Boss pedals, including a CE-300 chorus, a DM-2 delay, a CS-2 compressor/sustainer, two CE-2 choruses, a BF-2 flanger, a PH-2 phaser and an OC-2 octaver.

"All of my guitars are supplied by Rudy's Music Stop in New York, and a guy named John Suhr does the work," says Knopfler. "My main guitars are Schecter Strats with Seymour Duncan Alnico Pro pickups and Dunlop 6110 frets in them. They are incredibly powerful guitars." The Erlewine Automatic "was made for me by Mark Erlewine in Austin. He supplies Billy Gibbons of ZZ Top with guitars, and mine is just a screamer. I call it 'the Pig'."

Knopfler used to play a Gibson ES-175 but says he no longer takes it on tour anymore because "every time I play it I start to play faster and faster."

"Generally I end up using the same guitar on the road that I used in the studio," he continues, "because in the long run, if I recorded with it, it has the best voice for that song."

With regard to voicings, Knopfler has certainly been stretching those of his band; into the seemingly unavoidable realm of keyboards, that is. Beginning on Dire Straits' second LP, Communique, and culminating on their fourth, Love Over Gold, Knopfler has melded his truly unique guitar sound with a well-orchestrated yet pleasingly sparse keyboard mix. What with two keyboard players in the band and keyboard-heavy soundtracks such as Cal, Comfort and Joy and Local Hero under his belt, it was probably inevitable.

Soundcheck practically over, Knopfler indicates that he would like to make a change in the set, and almost instantaneously the air is filled with an awesome barrage of keyboards. Alan Clark and Guy Fletcher are joined by yet a third pair of hands, those of chief keyboard technician Ron "Ronnie from Bromley" Eve, who during Brothers in Arms plays a Yamaha DX7 programmed to sound like an accordion. Clark, a veteran of Straits since 1980, plays a MIDI'd Yamaha G3 grand piano, a Hammond C3 organ, an E-mu Emulator II, a Sequential Circuits Prophet 5, and Yamaha GS1, KX88 and DX7 keyboards, all pumped into an RSD16/8/2 mixing board, modified by Yamaha and Korg digital delays, a Yamaha R1000 digital reverb, and powered by Yamaha P2100 amplifiers and Frazer Wyatt keyboard cabinets.

On the other side of the stage, newcomer Fletcher — who came to the band via Roxy Music and who worked with Knopfler on the Cal and Comfort and Joy soundtracks — also has an impressive array of new technology: Yamaha DX1 and DX7 synths, New England Digital's Synclavier, Korg's CX3 organ and Roland's JP-8 synthesizer. He mixes down into a Seck 10/4 board, and modifies his sound with Ernie Ball volume pedals, Yamaha sustain pedals and a Roland SDD-2000 digital delay. Like Clark, he also powers up with a Yamaha P2100 amp and Frazer Wyatt keyboard cabinets.

"We've got some interesting setups, and we've also had our share of problems," says Bromley. "The Yamaha G3 has been modified with Forte Music's MIDI Mod, and we mike it with C-Ducer tape mikes and two Crown PZMs. We're also using four Leslie 147s with cycle changers that work — a rarity these days. Two are on stage for Alan's Hammond and Guy's Korg, and two are offstage, miked with Crown PZMs. Problems have arisen with the Emulator II and the Prophet 5; both have this serious problem of dumping their memories every time there's a power surge or the unit overheats. I even had to load the Prophet's memory from a cassette deck during the show once; it's ridiculous! My other biggest complaint is the cabinet they built the Synclavier into. It's so cheap that the whole thing fell apart, and I had to make my own cabinet for it. You'd think that for twenty-one thousand dollars they could make it roadworthy. I hate that attitude in manufacturing."

Brothers in Arms is generally regarded as Dire Straits' best-sounding album to date. It runs the gamut, from standard Straits' power twangers (Money for Nothing, The Man's Too Strong) to lilting opuses such as Why Worry and So Far Away, to keyboard/guitar exercises like the title track. Of course, there's plenty of Knopfler's undeniable unfashionability: numerous six-and seven-minute songs in this era of three-minute Pop packages. Throughout his career Knopfler — a one-time schoolteacher and a Rock critic for the Yorkshire Evening Post — has defied convention and avoided the Pop-star wagon train.

"I think if you look at the song Brothers in Arms, it has good depth, good melody and good orchestration," he says. "But then if you look at songs like Walk of Life, they are in many ways throwbacks to the way our music's always been. The thing about Brothers in Arms is its range of music as opposed to its being more orchestrated. I wouldn't say it's more orchestrated than Love Over Gold, though there is some of that in there."

The Dire Straits show starts out with a whimper instead of the usual bang, but you shiver nonetheless. The opening chords of Ride Across the River, a moody, slow-paced number, fairly hypnotise the crowd as Knopfler, dressed in his trademark red and black cowboy shirt and red headband, strolls out with a sunburst Strat and jumps into the opening lines. Illsley takes command of the left side of the stage and coaxes a beautiful low end out of his Fender Jazz bass, which he will play for the entire evening. Joined under the red glow of stage lights by a Stratocastered Jack Sonni, the group tears through Expresso Love, So Far Away and Romeo and Juliet without taking a breath. Knopfler's guitar playing has never sounded better, but the guitar non-hero is forever sketchy about his prowess.

"I haven't improved as much as I should," he laughs. "there was a slight improvement between Making Movies and Love Over Gold because I spent sometime at home just learning some new chords. But during this tour," he notes, "I'm going to be teaching myself more guitar on a very intense basis. Every new thing that I learn, I try to work out what its connections are, what its implications are, and then I put it to use."

With the spotlights still dancing off his well-polished National Steel, Knopfler trades it for his Adamas acoustic, Sonni trades his Strat for a Steinberger GL-2, and the Straitmen are off and walking ("Springsteen has the franchise on running," quips Knopfler) through an extended version of Love Over Gold — Hammond and Leslies blasting. So what does attract Knopfler to piles of keyboards and make him work so hard at achieving a balance between the two?

"Very often I use keyboards as a texture of strings," he explains, "or as some kind of texture or backdrop over which I will say something with the guitar. I'm always searching for textures that work, and a lot of it is just trial and error. You eliminate a lot of things, try out different things, work on things you know you can do better, and just keep on searching. Using keyboards is just adding vocabulary to a song. Each one has its own character, its own voice. I use about eight different guitars for the show because they all have their own voices and are all good for different things. Even though I'm surrounded by all this high technology, what I'm actually dealing with is a piece of music; feelings. I'm not a very technical person, so it's never been a problem for me to balance technology and feelings.

"You know, every time I approach the guitar I feel as if I don't know anything," claims Knopfler. "It's amazing; I'm going to be learning on the guitar when I'm 70. That's the way the instrument is. The best way I can express it is that I think I've got a bit of soul when I play, but as far as vocabulary is concerned with the instrument, I feel as though I can say, 'Hello, how are you?' on it, and that's about it.

"I am hoping that by the time I get ancient," he chuckles, "I'll be able to carry on a reasonably fluent conversation with the guitar."

A luthier writes...

Mark is very particular about the cut of his necks. The one I just made for him was a leftover Schecter that hadn't been fretted or shaped yet. I finished the cut on it, copying a '61 Fender Strat neck, only I made it feel a little bit nicer. He gets so particular about his neck/fingerboard edges that I cannot start out with a pre-cut neck because the edges are too sharp for him. He likes them round, but he also likes them very thin. I must have spent an entire day on that neck. He also prefers more of a radius on the fingerboard than on a stock Schecter. He likes the radius to be 10", whereas Schecters are 12", old Fenders are 6" and Charvels are 15". He likes his action real low and doesn't want his strings to choke when he's bending up notes.

I also copied the headstock exactly like that of a '61 Strat and fitted it with Dunlop 6110 frets. The body was originally cut by Tom Anderson, former technician from Schecter, then I painted it white and finished it off with a tortoise shell pickguard, Seymour Duncan Alnico Pro pickups and a Fender bridge.

I don't think Mark knew we were making him the white Strat, because when I was working on one for Jack Sonni, Rudy said to me that we should make one for Mark as well. Of course, when I was halfway done with Jack's, Mark saw it and said he'd really like to have a '61 style white Strat with a tortoise shell pickguard built, the way he really wanted it. Basically, he wound up with a '61 Fender Stratocaster built the way it should have been built when it was an original. It's a really beautiful instrument and he told Rudy it's his favourite guitar so far.

[Sigh]I would have loved to own it.

John Suhr

Publisher: International Musician & Recording World - Cover Publications Ltd, Northern & Shell Ltd.

The current copyright owner/s of this content may differ from the originally published copyright notice.

More details on copyright ownership...

Interview by Michael Smolen

Help Support The Things You Love

mu:zines is the result of thousands of hours of effort, and will require many thousands more going forward to reach our goals of getting all this content online.

If you value this resource, you can support this project - it really helps!

Donations for March 2026

Please note: Our yearly hosting fees are due every March, so monetary donations are especially appreciated to help meet this cost. Thank you for your support!

Issues donated this month: 0

New issues that have been donated or scanned for us this month.

Funds donated this month: £0.00

All donations and support are gratefully appreciated - thank you.

Magazines Needed - Can You Help?

Do you have any of these magazine issues?

If so, and you can donate, lend or scan them to help complete our archive, please get in touch via the Contribute page - thanks!