Magazine Archive

Home -> Magazines -> Issues -> Articles in this issue -> View

CXtensions | |

Yamaha CX5M SoftwareArticle from Electronics & Music Maker, December 1985 | |

Three packages for the CX5M — eight-track real-time sequencer, DX21 voice editor and RX editor — are put through their paces by E&MM’s review team.

With a recent dramatic drop in price and the arrival of some ancillary hardware, Yamaha's CX5M is back in the music computer limelight. We look at three new software packages that aim to keep it there.

Sequencing with the DMS real-time software

Software - 8-track Real-time Sequencer

Designed by Digital Music Systems

Reviewed by David Ellis

Many moons ago, when Star Wars was confined to the sanity and safety of the big screen, and attaching the tag 'music computer' to an MSX micro was thought to be a good marketing ploy, it was being touted around the programming fraternity that if you made all the right noises about Yamaha and their CX5M, you might just get a look-in on the software development.

And even given the high price attached to the computer's UK materialisation, life generally boded pretty well for the CX5M. With its self-contained FM synthesis capability and built-in MIDI, programmers have been attracted to it like bees round the proverbial honey pot. But there have been problems.

For a start, there was the unfortunate fact that the proposed MSX disk drive would be vying for the same memory space as software routines concerned with shifting data between the MIDI, the Z80 processor, and the SFG01 FM synthesis chip — the so-called 'music BIOS'. That meant none of the initial release of software would work with a disk drive.

Then people started questioning what was preventing the CX5M from being used as a MIDI expander module. And why the FM Composer and Voicing cartridges wouldn't work with a DX7 connected to the CX5M's MIDI In.

Finally, when Yamaha's own real-time MIDI sequencer software seemed to be subjected to some massive conceptual DDL, it wasn't long before CX5M owners started feeling a little disenchanted with their investment.

The root cause of a lot of this has been the way the inner workings of the CX5M have always been jealously guarded by Yamaha. What goes on in that mysterious music BIOS has been forbidden territory for all but the very few to pass Yamaha's positive vetting procedure. The nearest you or I could get to appreciating what made the CX5M tick was a set of four thick folders containing all the entry points needed to use the music BIOS routines — but not, of course, listings of the routines themselves. Yet even this was available only on special demand from Yamaha UK, and then only in the form of a sort of hi-tech chain letter which required you to remove your name from the top of an accompanying list of names and addresses, copy all the bumpf, and then send the folders on to the next name on the list...

Still, details of what the music BIOS gets up to are now emerging at last, albeit in the form of various discreet asides made by Yamaha employees in the States. For instance, according to Jim Smerdel of Yamaha International Corporation, the problem relating to using the CX5M as an expander module is that 'the software routine (in the music BIOS) used to communicate with the synthesiser chip takes so long to do its work that bytes of incoming MIDI data can be lost'. And the result of this sloth? Well, various companies in the States have offered to rewrite the CX5M's music BIOS to get around this further example of MIDI delaying tactics. Sad to say, Yamaha are sticking to their guns of nondisclosure.

Considering all the mystery and intrigue that's collected around the programming side of the CX5M, and a worldwide MSX takeover that's taken place with all the action and verve of a Japanese tea ceremony on a wet Monday afternoon, it's hardly surprising that software packages independent of Yamaha's haven't exactly been thick on the ground.

In fact, the Real-Time Sequencer from UK firm Digital Music Systems is the first to have made its way into commercial reality from any of the more musically-aware members of the European Economic Community.

"Documentation - With a meagre 11 pages measuring just three inches square, the manual has to be my Guinness Book of Records nomination for the meanest ever."

The CX5M is currently battling on with a much-reduced price tag of just £299 for the small keyboard version with one software cartridge (hints of a DX9-like stock clearance methinks; is it to make way for the forthcoming CX7M?), and there have also been some generous discounts to schools, so it might just be that the combination of a new pricing policy and the DMS software is just what's needed to give a flagging horse a much-needed boot up the backside.

Anyway, the DMS software package stems from the joint work of CX5M owner and programmer Abdul Ibrahim, and Sounds Great, one of Yamaha's hi-tech retail outlets in Cheshire.

It seems Ibrahim was originally selected by Yamaha in the UK to develop some real-time sequencing software independent of Yamaha in Japan. But according to Phil Lyon of Sounds Great, Yamaha then lost interest in the real-time side of the CX5M because of the music BIOS problems, so Ibrahim was left to fend for himself. That was when Sounds Great became involved in the project, and the £84.95 cartridge currently on sale direct from DMS (and, ironically, also from Yamaha's other hi-tech dealers) is the eventual result of that collaboration, and a lot of hard work on Ibrahim's part in disassembling the problematical music BIOS.

As with Yamaha's own CX5M software, DMS' offering is contained in 16K-worth of ROM, in the form of a cartridge that plugs into the CX5M's cartridge socket. You're advised (wisely) to switch off the micro before you insert the cartridge or swap cartridges. Of course, the major advantage of ROM-based software is that the software is up and running more or less immediately, but there are disadvantages, too, as we'll see later.

Accompanying the cartridge is what passes for a manual. But with a meagre 11 pages that measure just three inches square, this has to be my Guinness Book of Records nomination for the meanest manual ever. It's bad news for a piece of software costing £85, even worse news if you're new to the CX5M and sequencing, and downright ridiculous if you've been under the impression that the MIDI was some kind of dress length that had come back into fashion along with the umpteenth repeat of Star Trek.

Fortunately for those with their heads in lo-tech sands, getting into the sequencer's range of activities is pretty straightforward, thanks to a menu-driven scheme that gets you where you want to get to with the minimum of fuss, with the help of some clear (though not inspiring) screen displays and the CX5M's five function keys. So for instance, the title menu offers five options: time signature (F1), Playback/Edit (F2), Record (F3), Load/Save (cassette or disk, F4), and Sync (internal or MIDI In clock, F5).

Heading for Record first, we find a display with a top line showing the amount of memory left (20,536 bytes at the start), followed by the bar number and a beat counter. Under that, there are more function key assignments for setting the CX5M's music keyboard to one of the eight possible sequencer parts, the phrase number to be recorded (up to 254), the number of bars in that phrase (set by the user), and finally, the tempo and metronome volume.

It's at this point that you turn to the manual to find out what 20,536 bytes equates to in terms of note events. It doesn't tell you. Justifiably niggled, you're then bemused why there doesn't seem to be anything reminiscent of a metronome emanating from the CX5M's internal speaker after you've pressed R for Record. The manual is no source of enlightenment there, either.

'Aha!' you cry, 'didn't DMS' advert mention Help screens?' Indeed it did, but for the life of me, I couldn't find anything along those lines in this software. In the end, experimentation seems to be the order of the day, and sure enough, connecting a phono lead to the CX5M's own 'sound' output reveals the metronome in all its square wave glory.

"Overdubs - No attempt is made to use the CX5M's decent graphics to show how phrases and parts knit together — so you're very much left blind."

Another point that isn't mentioned in the manual is that the keyboard only comes alive once the eight-beat count-in is over. Personally, I prefer to play along with the count-in to get in time with the metronome, but perhaps that's a minority interest.

However, a more important point worth making at this juncture is that DMS' software is limited to the real-time antics of the YK01 or YK10 keyboards, not those connected via MIDI In. I'll repeat that: not via MIDI In. It's worth spelling that out, because it's certain that many potential purchasers will have jumped to the conclusion that DMS' package does what Yamaha's own real-time software prospectively does: take in event data via MIDI In. A direct consequence of this is that the only event data the DMS sequencer records is that pertaining to pitch and duration. Which means all the joys of velocity, aftertouch, program changes, and modulation wheels are absolutely verboten, as neither the YK01 nor the YK10 keyboard provides the means for sending that sort of extra-curricular expressive activity.

Still, 20,536 bytes filled with such simplistic event data does at least translate into a fair whack of notes, so maybe DMS aren't totally guilty of throwing out the baby with the bathwater. But as there's no scope for punch-in/punch-out correction of mistakes, or even appending to the end of a previously-recorded phrase, it's very much in your own interest to get it right first time.

What editing facilities exist in the DMS package (accessed in the Edit Phrase Data option) are a little on the primitive side, but the step-time pitch correction works well enough, and the auto-correction does what most people would expect of it within the limits of duration values between 1/4 and 1/48.

Having entered the raw phrases and patched up pitches and timing where necessary, the next stage is to proceed to the Edit Part Data option from the Playback/Edit menu. This allows you to assemble parts out of previously recorded phrases. Since democracy rules amongst parts and phrases, any particular phrase can be played by any particular part.

Sequencing with the DMS real-time software

Less enamouring is the fact that individual phrases can't be transposed within a part, though the overall part can be transposed relative to other parts. Also less than brilliant is the fact that the software provides no means for totting up the number of bars used in each part. To add to the list of deficits, no attempt is made to use the CX5M's decent graphics to show how all the phrases and parts knit together on all eight tracks. In fact, you're very much left blind when it comes to organising the contents of one part relative to another, so you'll need to be pretty well orientated in time and space (ie. not pissed) during your dealings with this software.

Finally, to get all the parts playing back with some sense of purpose, it's off to the Set Part Voices option to channel the parts to the CX5M's MIDI Out or the internal FM voices. Note that unlike Yamaha's FM Composer, DMS doesn't let you send a single part via both MIDI and to an internal voice at the same time. Shame really — I've always found that a good way of thickening some of the CX5M's less than thick voices.

In addition to the standard set of 46 CX5M voices, DMS provide their own set of 46, and there's still space for loading yet another 46 from Yamaha's FM Voicing software. That adds up to a total of 148 presets available for assignment to the eight parts, which I reckon to be generous by any standard. Still, I'd happily ditch 100 of those for the facility to construct and alter voices from within the context of the sequencer software, rather than having to go through the palaver of using the FM Voicing cartridge just to twiddle one envelope.

Jotting down my niggles with the way the software runs, I find quite a number — which is a bit worrying for a ROM-based package.

First, if you press one of the function keys (say, F2) instead of a numeric key (say, 2) in response to the request for a phrase number or some other parameter, the display comes up with the word 'auto' after the prompt. Similarly, F1 gives 'color', F3 gives 'goto', F4 'list', and so on. Now, pressing a function key isn't the most intelligent thing to do if you've been asked to enter a number, but it's the sort of thing anyone might do in the heat of the moment, and to be greeted by these strange words whenever you do is mildly off-putting. In fact, as anybody who's struggled with programming an MSX micro will know, the function keys also provide certain key commands ('goto', 'color', and so on) when you're programming in BASIC.

"Voices - There are a total of 148 presets available for assignment to the eight parts, which I reckon to be generous by any standard."

The fact that these words appear in the context of DMS' software merely shows that the key-handling routines aren't as foolproof as they might be.

A similar sort of thing happens when you put together phrases to make parts. Here, the F2 and F3 keys get used to move the column of phrase numbers in front of what the manual calls a 'pink pointer'(!). Quite why DMS didn't use the CX5M's cursor keys for this purpose is beyond me, but my niggle is that the auto-repeat on these keys is so fast that just a slight touch sends the column to the top or the bottom before you know what's hit you, making it difficult to zero in on a particular phrase you want to change.

Then there's the annoying fact that if you keep your mits on the keys when leaving the Set Part Voices option for, say, the Record menu, the notes being played drone on through the count-in until the point where you're meant to start playing. And you can't blame that on a MIDI keyboard failing to obey an 'all notes off' message!

Finally, there's the curious paragraph in the manual (under the blindingly user-friendly heading of 'garbage collection') which suggests that all is not quite as it should be at t' mill.

This says: 'make sure that phrase one is the first that you record. However, do not ever allocate phrase one to any part, the reason being that phrase one is used by the system as a garbage collector for the system's own internal house-keeping.' There's also a line that suggests the user should make sure 'that the last phrase in any sequence is an empty phrase, ie. a phrase that is yet to be recorded'. That's messy and not a little confusing. In my book, garbage collection is something that goes on when all good little boys and girls are asleep, not in the broad daylight of a supposedly professional piece of software. Very strange.

Of course, quirks like the above aren't confined to home-grown software. Yamaha's FM Composer is a case in point, and many reluctant entymologists have served their apprenticeship discovering its idiosyncracies (like the tendency to drag its feet when overloaded with notes or sync pulses, for instance). That said, there's still very little at the low-cost end of the market that comes anywhere near the Composer's ability to accommodate variations on an expressive theme.

True, if you go the whole hog and add variable accents, dynamics, articulations, velocity, vibrato, and program changes on every beat, you'll end up with a screen full of numbers and very few notes — not to mention a severely overtaxed Z80 chip and some very sore fingertips. But at least it's all there (well, most of it anyway) if you want it.

Sadly, Digital Music Systems' software veers too much in the opposite direction. It eschews expression in favour of simplicity. It also chickens out of using intelligent graphics to make its use more enjoyable by those musicians less than enamoured of the action of endless function keys.

To be fair, there's no doubt the DMS software adds another, much-needed string to the CX5M's bow, and one that's been sadly missing from Yamaha's currently available repertoire of ROM cartridges. The trouble is that viewed against the competition of other real-time MIDI sequencers, whether standalone (Korg SQD1, Casio SZ1 and so on), or micro-based (UMI2B, JMS' 12-track Recording Studio, LEMI's Future Shock, or Syntech's Studio, to name but a few), the DMS package has a fair way to go before it attains the status of any of them.

If you've got a CX5M that's been lying low of late since you came to the conclusion that Yamaha's own highly-prospective real-time MIDI sequencer was just another example of Japan slipping off its continental shelf, then DMS' package should be just what you've been waiting for. The 400 names DMS already have on their order books show there are more than enough real-time-hungry CX5M owners out there prepared to part with what is only a moderately inflated price-tag of £84.95. For how long they'll put up with a package that provides no facility for coping with MIDI In data, let alone adding all-important expression, remains to be seen.

That's an unfortunate conclusion to have to reach, really, because the fact that Abdul Ibrahim has managed to sort out the ridiculous tangle Yamaha got themselves into with disk drives on the CX5M is a major point in the package's favour. Even so, at £399 for the Yamaha disk drive and its interface, it's hardly likely that many CX5M owners will feel like availing themselves of Ibrahim's ingenuity. Indeed, they'd be foolish to do so when £399 can now buy you not only a 3.5-inch, double-sided, double-density disk drive like Yamaha's, but also a 128K CP/M-compatible computer, a monochrome monitor, and a printer that's capable of near-letter quality. The product is Amstrad's remarkable new word-processing package, and it's in your shops now.

Finally, DMS' software raises the thorny problem of what you do if you discover a bug in cartridge-based software. Sure, you can complain to the manufacturers, but as Yamaha's FM Composer software has demonstrated, it seems that once you've bought a ROM cartridge, you're stuck with it for life, warts and all. The DMS software clearly does have a few, admittedly minor, bugs in it.

I'd suggest DMS include a software update facility in the package's purchase price. After all, surely it's better to have satisfied customers than to add to the CX5Ms (and attendant software cartridges) that are up for sale in E&MM's classified ads?

Screen examples of Yamaha's DX21 Editor

Software DX21 Editor

Designed by Yamaha

Reviewed by Simon Trask

Let's consider, for a moment, the sort of job a typical Editor program should do. Put simply, an Editor is an alternative way of presenting patch parameters, which takes advantage of the fact that a monitor screen is capable of displaying more things more clearly than yer average LCD or LED display window.

The idea is that, by being able to see all the parameters and associated values of a synth patch, you're more likely to appreciate what the components of the sound are and how they interact. Which, in turn, should help you change things around to get the sound you want more quickly.

This approach has become even more useful in recent years, with the advent of digital access synths (which is most of them nowadays) that only let you edit one parameter at a time, and with the appearance of FM synthesis, which is still something of an unsolved mystery to many people, despite the fact that so many musicians now own a Yamaha DX synth of one description or another. If all synthesisers are novels, the Yamaha DXs could have been written by Agatha Christie. So it helps to be able to put all the characters up onscreen and find out where they all were on the night of the 14th, or whichever patch number you happen to be working on.

But let's not get too carried away. Just as a MIDI sequencer won't turn your monotimbral synth into a multitimbral wonder, so an editing program won't let you manipulate more than one parameter at once when the synth itself allows manipulation of only one.

Yamaha's DX21 Editor scores well in the display category. The screens are clear and uncluttered, the choice of colours pleasing (not a consideration to scorn if you're working at all extensively with software).

Screen examples of Yamaha's DX21 Editor

On power-up (the program is on cartridge), the Directory page appears on-screen, and the current contents of the DX21's RAM are automatically downloaded to the CX5M. The Directory page displays the names of the RAM voices, and besides numbering them, divides them visually into the DX21's eight-voice banks. There are six of these, which the alert among you will realise makes 48 voices. Seeing as the 21's RAM consists of 32 voices arranged in four banks, this arrangement seems slightly odd at first. However, the extra voice positions are useful, as the Editor allows you to move single voices around to any position and swap banks around with gay abandon. Only the first 32 positions converse with the DX21 over MIDI, so the extra positions are quite useful as 'safe' areas.

Changes made in voice positions within the Directory are not instantly transferred over MIDI. You have to go to the File page (all pages are accessed by pressing the CX5's Function keys) and select MIDI in order to instigate loading and saving of voice data over MIDI. Sensible enough.

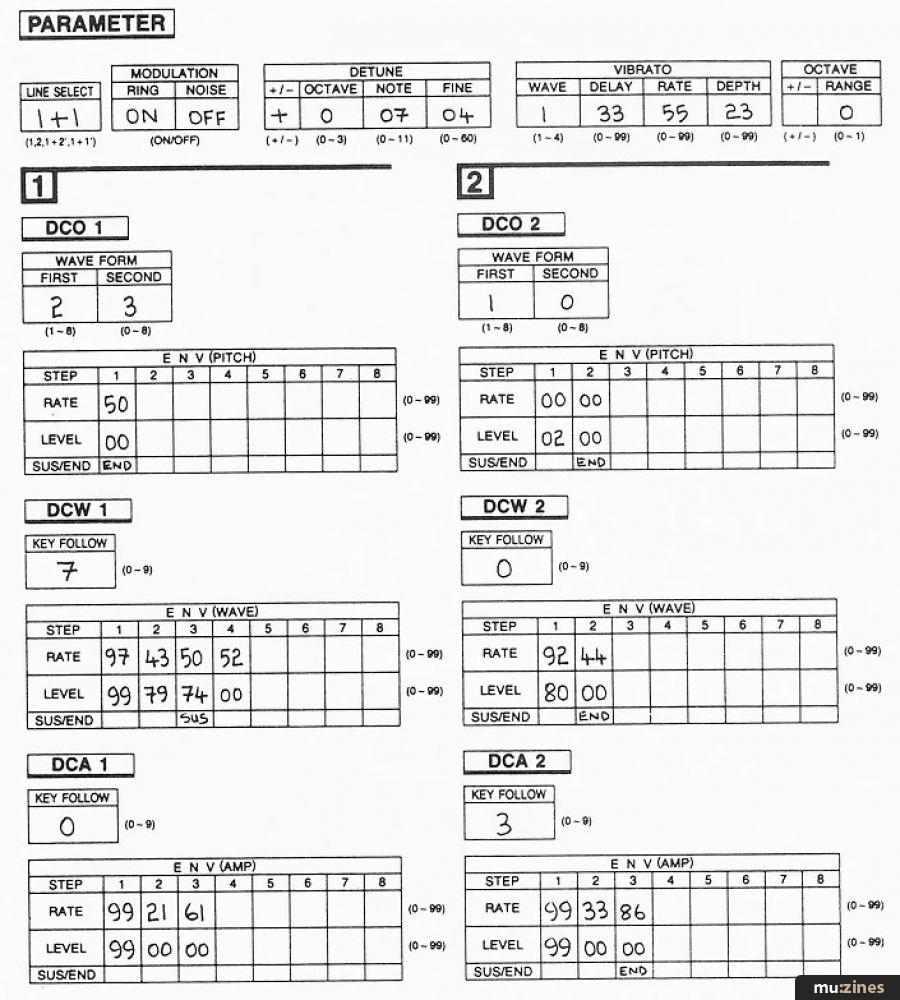

There are two pages for displaying voice parameter data, though one of these is for viewing and printing out only; this presents the information in the standard data sheet format found in the DX21's manual.

The other screen is where parameter editing is carried out, and this presents a selection of the parameters in a neat, logical, and easily accessible layout. As you'll see from the accompanying photos, midscreen is taken up with envelope, frequency and output level parameters for each of the four operators. Information which is not operator-specific appears in the upper and lower portions of the screen, and it's here that you can flip between different displays (eg. between LFO and Pitch Envelope Generator parameters in the upper portion of the screen). Usefully, you can flip between parameter groups from the QWERTY keyboard, so there's no need to use your DX21's front panel at all.

"Display - The Editor scores well in the display category — the screens are clear and uncluttered, the choice of colours pleasing."

"Features - The 21 doesn't transmit performance memory data, so you're not going to find a performance memory save/load feature on the Editor."

Parameter changing can be accomplished either from the DX21 or from the CX5M's QWERTY keyboard, with changes registering instantly on both the synth display and the monitor screen. Movement around the latter is achieved with the cursor keys (the currently selected parameter is highlighted by a flashing cursor bar), while parameter value altering is achieved with the Home and Delete keys (these also function as Yes/No selectors). All of which makes onscreen access a quick and painless affair.

Most of the multi-value parameters are presented in either of two forms: as horizontal bar-graphs or (in the case of volume/timbre and pitch envelopes and rate scaling) as x-y axis graphs. These can co-exist on the screen quite happily, so one operator's envelope could have a bar-graph display and the other an x-y display simultaneously, and you can flip between one and the other at any point.

In most other respects, the DX21 Editor is restricted — as all editing packages are — by the information the host instrument can transmit/receive over MIDI. Thus, for instance, the program can upload all RAM data automatically from the DX21 on power-up, because the 21's MIDI implementation lets it receive a 32-voice dump request, upon which it transmits all the relevant data. But equally, the 21's MIDI implementation doesn't allow for the transmission of performance memory data, so you're not going to find a performance memory save/load feature on the Editor.

Regardless of MIDI, though, editing software can offer an increased number of storage possibilities, taking advantage of the peripherals normally associated with a general-purpose computer.

So whereas the DX21 on its own is limited to cassette storage, it's possible via the CX5M to store voice data to disk, cassette or data cartridge.

Yamaha's own disk drive is now available at last, and uses the now standard 3.5" disks, available from all good computer stores (as the saying goes). But the drive itself is expensive enough to cause a minor epileptic fit in those susceptible to them, and the Editor package allows you to save only 32-voice dumps to disk. Still, with a 720K formatted capacity, you should be able to get a fair few dumps on each floppy.

Screen examples of Yamaha's DX21 Editor

If you want to use cartridge storage, you'll need Yamaha's cartridge adaptor (£19), which lets you make use of the CX5's second cartridge slot while the first is occupied with the Editor. Unfortunately, the cartridges themselves cost — wait for it — £65. Considering each cartridge only takes a single 32-voice dump, this option sounds even less feasible than going for disks.

Cassette storage also allows you to dump a whole set of 32 voices — though given the slowness of tape storage, it would have been quite nice to have been able to do bank dumps as well. MIDI storage is, obviously, to/from the DX21, and again deals in complete 32-voice dumps.

Storage problems aside, the DX21 Editor is an attractive alternative to fumbling around with the synth's own meagre display. There's just no comparison between the comprehensive, informative CX5M displays and the DX21's front panel, nor between the ease with which you can move around the edit screen and alter values on the CX5M, and the tedious button-pressing you have to do on the synth.

FM is still like Agatha Christie. But at least there's a film version now, not just a book.

Graphic details of Yamaha's RX Editor

Software RX Editor

Designed by Yamaha

Reviewed by Trish McGrath

Just as keyboard players the world over have been heard to mutter 'what ever did we do without touch sensitivity?', so owners of RX11 drum machines and CX5M computers will soon feel the same about Yamaha's new RX Editor. Because the Editor will literally reach parts of the RX you never knew existed.

The program allows you to create patterns in step time from the CX5 or a MIDI keyboard, or in real time from an RX11, RX15 or MIDI keyboard (preferably a velocity-sensitive one). And it offers extensive editing facilities in both pattern and song modes.

If you connect an RX11, the Editor automatically downloads the data contained in the drum machine for editing or further programming (note that the RX15's MIDI implementation doesn't allow for the downloading of data in this way, contrary to what the handbook says). And the program is compatible with the budget RX21 (set the 21 to Channel Info Avail), with the same facilities as offered to the 15, other than the ability to edit instrument pan positions.

In fact, I see no reason why the program shouldn't be compatible, at its most basic level of triggering voices with some degree of dynamics, with any MIDI drum machine whose voices are accessible in this fashion, like the TR707/727, Drumtraks, and so on.

First off, the System Set Up menu requires you to select which one of four configurations the computer is dealing with, ie. either RX11 or 15, both either with or without input from a MIDI keyboard. From here, you can select Omni On/Off, the System Exclusive MIDI channel number, the channel number for each instrument, and the MIDI key note relating to each instrument. Synchronisation defaults to the CX's internal clock, but you can set the Sync Mode to accept or send the MIDI Clock if need be. For printing out screen displays, you can select between MSX and Epson printers, and set the speed (Northern Line crawl to Ferrari race) at which the cursor moves round the screen.

Each of the four main menus, Pattern Editor, Song Editor, System Set Up and Filer, are selected by pressing either a function key or moving the cursor to the appropriate icon and pressing Return, while most of the settings and values are selected by moving the cursor to the desired area until that area starts flashing; you select a new setting using the Home (-) and Delete (+) keys. Before long, moving around the Editor becomes almost second nature — and no doubt the optional mouse makes this quicker still.

Let's assume a certain familiarity with the spec of the RX drum machines, and go straight to the Pattern Editor. This is where you name, define, create and edit patterns using the now tried-and-tested grid. This makes room for eight instrument names and 18 steps before it scrolls down and across as need be. So if you tend to write multi-bar patterns, you'll have to do a lot of scurrying across the screen inputting and editing notes — though you can escape from the grid (by holding the Shift key down) without having to scroll to its extreme.

During playback, you depend very much on the beat counters to let you know where it's all at, as the grid is a bit of a non-scroller. Fortunately, the counters indicate the current beat and bar during playback, with an arrow moving, and a couple of dots blinking on and off, in time with the beat. And aside from a tempo indicator, a useful seconds counter runs with the pattern or song chain.

Creating patterns using the QWERTY keyboard is a matter of defining the time signature, number of bars, and quantisation necessary, compiling a list of instruments from a pull-down menu, and pressing the space bar at the steps where you want instruments to sound.

"Features - RX11 owners can set the velocity of each note played by each voice — a real feel-injector of an option if ever there was one."

"Storage - You can't dump data directly to or from the RX15, so you'll need one of the CX5's storage mediafor storing ana retrieving data."

If you're inputting from a synth, you use the cursor keys to home in on a step, and then strike the appropriate note. Which is a bit slower, but has the advantage of allowing dynamics to be programmed at the input stage, provided your synth is velocity-sensitive.

In Real Time Write (RTW) mode, the space bar sets the metronome running, and input can be from either the RX or a synth. Once you ESCape from RTW input, your pattern is displayed on the grid for you to play back what you've written or edit further. Deleting a misplaced note is carried out by moving the cursor to that step and pressing the space bar a second time, or in RTW by pressing Shift and the instrument button in time with the offending notes — easier said than done.

The Instrument Function menu lets you delete an instrument from a pattern, delete just the notes that instrument was deemed to play, copy the notes of one instrument into another, and move the order of instruments around within the grid.

Meanwhile, the Pattern Functions operate on the pattern as a whole, and allow you to clear all the notes (leaving just the instrument names), clear the complete pattern (from whence you can redefine it and start from scratch), recall the state of the pattern prior to using the Editor, and copy or append another pattern to the present one. And in case your fingers slip, each and every selection can be 'undone' afterwards — so don't panic.

Right of the grid is the Pan/Level/Instrument display, which cycles to indicate the pan setting of each instrument, the overall level for each instrument, and, in the case of the RX11, the instrument tone selected. You can edit all those parameters at will, too.

What else can the Editor do that your drum machine alone can't? For one thing, the velocity of each note can be set over a range of 1-8 relative to the level set for that instrument. This is a real feel-injector of an option if ever there was one, and is especially good at instilling life into hi-hat patterns. And cleverly, the graphics indicate the volume of each note by increasing or decreasing the size of the dot that represents it.

If you home in on a note and press Return, an expanded diagram (reminiscent of a miniature Golden Shot) appears bearing details of the velocity, timing, and pan settings for that note.

Pronunciation Timing is the term given to the movement of a note forwards or backwards in time in intervals of 96th-notes (maximum is 2/96 before and 3/96 after the beat), which, if you use it wisely, can simulate yer average 'human' drummer after 10 pints of Kronenbourg.

For RX11 owners, the Editor allows you to stipulate the pan position of each note for each instrument — great for autopanning tom rolls and other marvels of stereo migration — and during playback, the pan indicators jump about like jack-in-the-boxes. Very entertaining. However, it's worth pointing out that the range of +/- 7 is relative to the position of the previous note, which means the expanded diagram can be somewhat confusing. For instance, if the display indicates 00 placement, it doesn't necessarily mean the sound is centre-panned — it's just that there's been no movement from the previous note's position. It also transpires that the maximum movement you can achieve between two consecutive notes is 7 units, which works out at half the stereo image. But then, who in their right mind would want to pan hard left and right in consecutive steps? Well, I might for a start. OK, so it can be disorientating, but Yamaha might at least have given us the choice.

Bear in mind, also, that the individual outputs from the RX11 are mono only, so you can only enjoy the innermost delights of this feature when the stereo outs are in use.

But pattern editing isn't the only area where the Editor offers extra facilities. The Song Editor does more than the usual linking of patterns.

Graphic details of Yamaha's RX Editor

For instance, after naming a song, you're free to link patterns together to form a song chain, which you can divide down into parts, and then play back either the complete song or just individual parts. Pattern input is made from another pulldown menu that displays the list of defined patterns and the various editing options available. While you're arranging your patterns into parts, you can place repeat signs on a part (from 01 to 99 repeats); instruct the chain to return to some previous part (the first time round) and repeat it a number of times (again, from 01 to 99); and insert parentheses in the chain, in which case the part is repeated until all the different endings have been played.

You can also instruct the song to adhere to the level balances set for each voice in a pattern, as well as the RX11 instrument tones set (so you can change from one snare or bass drum tone to another). This is best done before the first part in a song chain, as otherwise the Editor defaults to whatever levels and instrument tones were used in the last pattern played. Pan settings and velocity adjustments inherent in a pattern are always followed, though, as is individual note panning in the case of the RX11.

Moving to the song as a whole, both tempo (+/- 50 units) and overall volume can be altered (in the range +/- 15 relative to the present level) in the middle of a song. However, I'd award a medium-sized Golden Turkey to the latter feature. The volume of the RX can be altered in a range of 0-63 — but the default value in the software is the maximum of 63, using a scale different from that used by the drum machine. This means that if you want to increase the volume in the middle of a song, you've got to set it to -15 to begin with, and increase it relatively from there. So instead of getting a dynamic range of 30 units, as you might think, you actually get one of 15. Which is a bit silly, really.

The Song Function menu allows for the clearing of a song, recalling the state prior to use of the Editor, copying a song to another location, and appending one song to another.

You can also send MIDI macro data, created by Yamaha's FM Music Macro software and loaded in advance from the Filer, between patterns.

In case you hadn't already guessed, the Filer is where all saving and loading is carried out between the CX5M and RX11, cassette, disk drive, data cartridge, the Watford Public Library, or any other storage medium you succeed in connecting. It's also where you're given the option to clear the entire contents of the Editor from the Function mode.

As mentioned earlier, you can't dump data directly to or from the RX15 (you can use Real-Time Write mode for the transfer of individual patterns from the RX15, but it's a bit laborious), so you'll need one of the other devices for storing and retrieving data. Which is no bad thing, really, since most of the extra features the Editor offers are eliminated once data is compressed for sending back to the RX11. So be prepared to build up cassette or disk libraries if you want to enjoy the additional features the Editor offers.

Our resident RX15 worked to rule during the test period, and refused to follow the pan positions set by the Editor (the software, not the man with the red pen behind his ear). Even giving Yamaha the benefit of the doubt, it still seems crazy to expect people to use the CX5M and associated hardware for creating and storing patterns, and then have to lug the whole circus with you to rehearsals and gigs. No more jumping on the tube with your RX15 under your arm...

All of which leaves me thinking the package is best suited to RX11 owners and brave RX15 users.

It's worth remembering that from the Set Up page you can set each instrument to a different MIDI channel number and key note value, which does allow for the simple sequencing of external MIDI devices, like your DX7's timpani patch, a gaggle of SDS9 toms, and so on.

It's debatable whether RX users will invest in a CX5M for the added benefits the Editor offers, but for CX5M owners looking for a decent drum machine, an RX11 would be hard to resist, and an RX15 still a good bet.

Because when all is said and done, the RX Editor makes pattern writing and song creation a rapid, straightforward exercise, allows specific and comprehensive editing, and presents a set of graphics that's nothing short of superb. One day, all drum machines will be programmed this way.

DATAFILE - CX5M Software

DMS 8-track Real-time Sequencer

Hardware requirements Yamaha CX5M, TV, cassette or disk driveSpecification 1 song, 8 parts, 254 (max) phrases

Main features Real-time monophonic or polyphonic input from YK01 or YK10 keyboards, metronome, autocorrect, pitch editing, part transposition, part muting, part volume, CX5M or MIDI channel assignment, sync from external MIDI clock

Price £84.95 including VAT and postage

More from Digital Music Systems, (Contact Details)

DX21 Editor

Price £39 including VATMore from Yamaha-Kemble, (Contact Details)

Yamaha RX Editor

Price £39 including VATMore from Yamaha-Kemble, address above

Featuring related gear

21 Today

(EMM Aug 85)

21 Today - Yamaha DX21 synthesiser

(ES Sep 85)

CX-5

(MIC Feb 90)

Fireball CX5M

(ES Oct 84)

June Calendar

(MM Jun 86)

Moving On - Yamaha DX21

(SOS Jan 86)

Technically Speaking (Part 3)

(MM Jun 86)

Technically Speaking

(MM Nov 86)

Technically Speaking

(MM Sep 87)

Technically Speaking

(MM Oct 87)

The CX5M Revisited

(EMM Mar 85)

Yamaha CX5 Computer

(12T May 84)

Yamaha CX5 computer

(12T Oct 84)

Yamaha DX21 - Synthcheck

(IM Sep 85)

Yamaha DX21 Synth

(12T Aug 85)

Yamaha RX Digital Rhythm Machines

(EMM Mar 84)

Yamaha's DX21 FM Digital Synth

(IT Jul 85)

Patchwork

(EMM May 86)

Patchwork

(EMM Jun 86)

Patchwork

(MT Feb 87)

Patchwork

(MT Jun 87)

Patchwork

(MT Dec 87)

Patchwork

(MT Mar 88)

Patchwork

(MT Jun 88)

Patchwork

(MT Jul 88)

...and 7 more Patchwork articles... (Show these)

Browse category: Synthesizer > Yamaha

Browse category: Computer > Yamaha

Browse category: Drum Machine > Yamaha

Publisher: Electronics & Music Maker - Music Maker Publications (UK), Future Publishing.

The current copyright owner/s of this content may differ from the originally published copyright notice.

More details on copyright ownership...

Gear in this article:

Software: Sequencer/DAW > DMS > 8-track Real-time Sequencer

Software: Editor/Librarian > Yamaha > DX21 Editor

Software: Editor/Librarian > Yamaha > RX Editor

Gear Tags:

Review by David Ellis, Simon Trask, Trish McGrath

Help Support The Things You Love

mu:zines is the result of thousands of hours of effort, and will require many thousands more going forward to reach our goals of getting all this content online.

If you value this resource, you can support this project - it really helps!

Donations for February 2026

Issues donated this month: 0

New issues that have been donated or scanned for us this month.

Funds donated this month: £0.00

All donations and support are gratefully appreciated - thank you.

Magazines Needed - Can You Help?

Do you have any of these magazine issues?

If so, and you can donate, lend or scan them to help complete our archive, please get in touch via the Contribute page - thanks!