Magazine Archive

Home -> Magazines -> Issues -> Articles in this issue -> View

Delirious Xcitement | |

Yamaha DX7SArticle from Sound On Sound, March 1988 | |

A story in which our hero, David Mellor, deserts the path of enlightenment and sells his DX7 Mk1 for a rival keyboard. Can the DX7S tempt him back to the true faith? Read on...

Brand loyalty is not something I set a great deal of store by. One year manufacturer X brings out a super new wonderful product, but if he doesn't better it next year I'll be off as quick as a flash to his keenest rival to see what they have to offer. The classified pages of my local newspaper are littered with ads for my old gear. It's not that I am one of those people who always has to have the newest and best, just that I find it musically inspiring to have a continually refreshed selection of sounds at my disposal.

I remember the excitement when I bought my DX7 Mk1. It was my first polyphonic keyboard and I was looking forward to the luxury of not having to endlessly overdub to build up chord sequences. I soon got the hang of programming it - in spite of the difficulties that some people were imagining - and recorded dozens of tracks using just that one synth, several of which are now earning me the coppers to support me in my habit (music!).

My love affair eventually fizzled out. I thought of writing to 'Dear Deirdre', but I knew what the problem was - over-familiarity. The DX voices, remarkable though they were, were beginning to annoy me. I sold the old DX and bought an analogue synth instead, with a Yamaha FB01 expander just in case I needed a fix of the old stuff.

The original DX7 was causing me some other problems too. For instance, when using it with a sequencer and expanders, it was so frustrating not to be able to play a different MIDI voice without hearing the DX as well - it had no Local Off mode. MIDI transmission on channel 1 only was a bugbear to some, though I didn't find it too worrisome.

Now, after a DX-less year, I find myself with the DX7's replacement - the DX7S - to review and I find my old passions returning. The sap is rising and all that sort of literary stuff. All those lovely crisp, penetrating sounds are there - the electric pianos, the basses, the flutes and clavichords. What's more, they're better than before and all the little annoyances have been sorted out. And, thankfully, Yamaha have at last got the DX7 down to a reasonably carry-able weight - you should see the length of my arms after lugging the old one all over London!

In the old DX days, Yamaha made four major varieties of FM synth - DX7, DX9, DX5 and the mammoth DX1. Now we seem to have several versions of the DX7 to contend with - the DX7S, DX7II and the DX7IIFD (floppy disk). For the last two, I refer you back to Sound On Sound March 1987, where they were well-covered. This review is all about the true replacement for the DX7 Mk1, which is what the DX7S is. If you are currently a DX7 Mk1 owner, then I hope to be able to show you how this is the same instrument, yet better. If you don't own a DX yet, then I envy you that your first experience with one is yet to come...

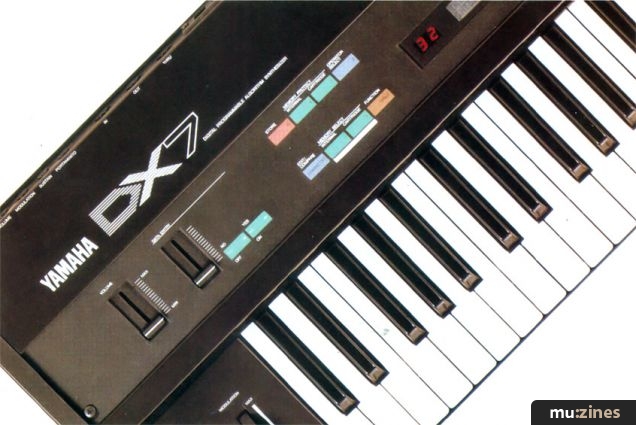

The DX7S comes in a fairly large plastic casing, rather than the metal box of the old type. A five-octave keyboard with pitch and modulation wheels is the norm these days and Yamaha stick to this system. Thankfully, all the buttons are of the chunky press-down type, not the membrane switches we all used to moan about. They give a reassuring click and always work first time. Three sliders are provided - Volume, CS1 and CS2. 'CS' stands for 'Continuous Slider' would you believe? More about the function of these in due course. As well as the 32 voice/edit pushbuttons, there are 10 which deal with the selection of functions on the DX7S. I do like to see an instrument with a full and logical selection of buttons. Economies in this department are not welcome, no matter how good a machine may be in other ways.

Diving straight in, most of us know the sort of sounds a DX can offer, so let's look at the editing facilities we have here: The first thing to explain is the difference between a voice and a performance in Yamaha's terminology. A voice is a collection of parameters applicable to the basic sounds of the instruments - whether string-like, keyboard-like, brass-like or whatever. Parameters such as operator levels, envelope timings, algorithm - these are all part of a voice. Performance parameters are more to do with the way you play the instrument, and a particular combination of parameters could be useful on more than one voice. Think of it, in analogy, as a band being recorded using a mixing console - each different instrument of the band is a voice, each EQ setting on the mixer is a performance. Some EQ settings may be applicable to more than one instrument.

The old DX7 certainly had plenty of Voice parameters and memories, but it could only store one Performance setting. This setting was applied to every voice you recalled whether it suited or not. To be fair, you could tell the Voice by how much it would respond to the different performance parameters, but this was a distinct bugbear.

The DX7S can store 64 Voices internally - twice as many as the Mk1 - and 32 Performances. Let's see what happens when you recall a Performance memory, eg. Performance 24 - 'Wirestring'. Pushing the buttons 'Performance' and '24' immediately recalls a whole set of parameters. Firstly the voice, for a named voice is included in a Performance setting. In this case, the voice is Internal 46, 'WireStrg A'. Strange name - nice sound. This is the raw voice, which sounds OK by itself but the Performance parameters are going to add to that. In this case, these are the settings:

- FS: soft

- FS soft = 5

- CS1 total level OP1

- CS2 total level OP4

- Total volume = 90

- Forced damp: off

- Microtune: equal

- Key shift = +0

- Name: Wirestring

- Voice number = I46

This probably doesn't mean an awful lot at the moment, so let me explain further: There are two footswitch sockets on the DX7S. Footswitch 1 is a conventional sustain pedal but Footswitch 2 can be set to operate in four ways: sustain; portamento (does anyone apart from Rick Wakeman still use it?); key hold or soft. 'Soft', as you can guess, softens the volume and timbre of the sound and is very good for harpsichords and clavichords. 'Key hold' functions like the centre pedal of a three-pedal grand piano; when you press it, any notes which are held on the keyboard at that moment are sustained for as long as you hold the pedal down. Any further notes are not sustained. If I had two footswitches in my bits-and-pieces draw I would have loved to have found out whether you could use key hold in conjunction with the conventional sustain pedal. I do hope that Yamaha have made this trick possible.

CS1 and CS2, the continuous sliders, can have a whole range of parameters allocated to them so that when you play, you have real-time control of two aspects of the voice you are using. On the old DX7 you had to remain in Edit mode to do this and there was only one slider to do it with. The choice of voice parameters available to either slider for real-time control is as follows:

Operator parameters (any operator from 1 to 6)

- Total level

- Amplitude modulation sensitivity

- Key velocity

- EG (envelope generator) level 4

- EG level 3

- EG level 2

- EG level 1

- EG rate 4

- EG rate 3

- EG rate 2

- EG rate 1

- Oscillator detune

- Frequency fine

- Frequency coarse

Other parameters

- Portamento time

- Pitch EG, levels 1 to 4

- Pitch EG, rates 1 to 4

- LFO (low frequency oscillator)

- Amplitude modulation depth

- Pitch modulation depth

- Pitch modulation sensitivity

- Delay

- Speed

- Waveform

- Feedback level

- Algorithm

- Total volume

- No effect

Does this come to 103 different possibilities? That's what the manual says and I believe it.

Back to the remaining Performance parameters; 'Total Volume' allows an overall level to be set for the Performance memory. Different sounds sometimes come out at different levels, so with this you can even things up.

'Forced Damp' is an interesting little concept. It's often thought that, because we humans only have 10 or fingers, the possibility of playing 16 notes on a synth at the same time must seem like slight overkill. Well, it is - until you use the sustain pedal. With this, you can have all the notes on the keyboard in a 'pressed' state. Since only 16 of them can respond, the best way to sort them out is to drop the first played (or oldest) notes to make space for the 'younger' ones. A bit like life really. Yamaha provide two ways of doing this: Forced Damp Off means that new notes, over and above 16, will not retrigger the envelope generator, so you get new pitches without the initial transient of the note; Forced Damp On makes sure that any old notes are pushed out of the way completely so that a new attack phase can occur. I can imagine that both alternatives will find full employment if you are a pedal pusher.

While I'm on the subject of sustain, I hope you'll excuse me for a moment if I get on my soapbox and ask manufacturers to consider making sustain work in the same way it does on a piano - not only do notes that are being played sound, but also notes which are harmonically related are stimulated into vibration by the action of resonance. This is why the sustain pedal gives the real piano such a warm, full tone. How about it chaps?

The subject of microtuning has been mentioned before so I'm not going to labour the point - and I'm not going to pretend that I know more about it than I do.

The DX7S, as well as its big brothers, can have the pitch ratios between the keys altered. We are well used to the concept of having 12 notes to the octave, and being able to play in any musical key - even the keys that are chock full of black notes! This is the system of 'equal temperament' which, roughly translated, means that the pitches of all of the notes on the keyboard have been 'tweaked' to make each key equally in-tune - equally out of tune is another way of saying it.

There are a number of different tuning systems in existence which sound subtly different. Yamaha give us the opportunity to experiment with these, and to try new ones of our own. There is a choice of 10 tunings on the DX7S, as well as the conventional equal temperament one, and two memory locations for storing your own tunings. Any note can have its pitch adjusted over the entire range of the instrument. Pity the display doesn't show the frequency in Hertz though.

In case you have forgotten, I'm still describing the Performance parameters. It's a long list, isn't it? The old DX7 seems especially primitive now with its lack of Performance memories - imagine having to cope with all this every time you wanted to make an adjustment. Next comes Key Shift, which simply determines whether the instrument will play in concert pitch, or transposed up or down to suit those awkward saxophonists. Performance Name is obvious enough, though it's worth mentioning that it need have nothing to do with the voice name. For any Performance, you can choose any voice you like.

VOICE EDITING

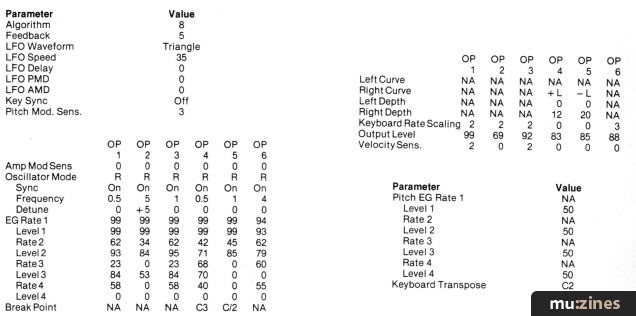

I could go back to the basics of FM synthesis here, but that would need an encyclopaedia rather than a magazine review, so I'll concentrate on the differences between the new DX7S and the DX7 Mk1.

New feature number one is the pitch envelope. The old DX offered only rudimentary control over the rise and fall of pitch during a note. This is now extended with control over the maximum range of the pitch variation, between half an octave and eight octaves. There is also a velocity parameter which enables control over the degree of pitch change to be determined by keyboard touch. One criticism I have is that the pitch change is always symmetrical: if the pitch rises at the beginning of a note, then it falls at the end and vice-versa. It would be nice to have a note which rose to its correct pitch, then stayed there throughout its duration. There is a trick that can get around this but it's not always satisfactory. It would be wise for Yamaha to have a look at this point, but it's not desperately important.

A big drawback to the DX7 Mk1 was the paucity of LFOs (low frequency oscillators). It's the LFO that gives a synth its soul and to have just one was a terrible oversight. This year's model now has 16 - one per note. OK, so I'd like to have one per operator, per note, which comes to 96, but I'm just greedy. Nevertheless, one LFO per note, even though they can't be set separately, is a huge plus. In the old days, when you programmed a bit of tasteful pitch modulation, every note you played swayed up and down in drunken synchronisation. Now, as you play different notes on the keyboard, their modulation comes in at slightly different times for each. This makes for a much more rich sound. It is still possible to have things the old way, if that's what you prefer.

Four key modes are provided to further 'fatten' up the sound. The normal situation is to have 16 independent notes. 'Monophonic' gives just one note, which is sometimes a help with difficult runs. 'Unison Poly' stacks four notes together, so you can only have four keys sounding at a time but they are four times as 'full'. 'Unison Mono' gives all 16 notes stacked up to create a super monophonic DX. Lovely.

Pitch bend is extended here to give four options: normal, lowest, highest and key-on. 'Normal' is the usual situation where all notes go up or down in pitch to the same degree. 'Lowest' means that only the lowest note played is bent, similarly 'highest' means that only the highest note played is bent. 'Key-on' selects pitch bend of all notes, apart from those held by the sustain footswitch.

With Pitch Bias, either aftertouch or the optional breath controller can be used to control the pitch of a voice. This is a nice one for getting realistic clavichord pitch bends and is also good for imitating the effect of lip pressure on wind instruments.

One feature of the 1983 vintage DX7, which was quite a novelty in its time, was the possibility of adjusting (scaling) parameters over the length of the keyboard. It was possible to have operators increasing or decreasing in level as the note got higher or lower, and there was a choice of linear, exponential or inverse exponential scaling curves. It's a problem of synthesis that you can get a sound 'right' for part of the keyboard, but it doesn't work in other octaves. This feature went a long way towards making things as they should be. In the new version, as well as retaining the old system, it is possible to access keys in groups of three and give each operator an individual level. It's a lengthy procedure, but if you are a megastar then you'll have your keyboard roadie do it for you. (When will Yamaha supply one of those?)

MORE MEMORY

So much for the new Voice features. Needless to say, the DX7S has got all the old stuff as well. I don't think my memory fails me when I say that there is no feature of the original DX7 which isn't present here - except the weight!

The organisation of the memory is rather more complex, so I think it is worth a little explanation. The internal RAM - which is, of course, battery-backed - can hold 64 Voice memories, 32 Performance memories, one system set-up and two user-defined microtunings. Cartridge memory can be a Yamaha-DX RAM4 which can store three different types of data: Voice/Performance, Fractional Scaling, and Microtuning. The Voice and Performance capability is identical to the instrument itself. Alternatively, 64 Fractional Scalings can be held - one for each instrument voice, or 63 Microtunings. Sixty-three? That's an odd number, in all senses of the word.

The DX7S is normally supplied with a ROM cartridge. Normally, I say, because it's well known that magazine reviewers are a lower form of life and can't be trusted to send them back - so I didn't get one with the review model. Fortunately, the owner's manual reveals that the supplied ROM comes with four memory banks.

Possible RAM4 Contents

Bank 1 contains 64 Voice memories, 32 Performance memories, two Microtunings and one system set-up. Bank 2 has the same, but different, if you know what I mean. Bank 3 contains Fractional Scaling data, while Bank 4 holds data equivalent to the originally supplied internal data. The cartridge is much more interactive than the old DX7 ROMs. Here is a quote from the Yamaha manual:

"Banks 1 and 2 can be loaded to the Internal Memory, but if you try to choose a Performance, you will still need to have the cartridge inserted. This happens because the Performance memories are calling Cartridge Voices."

I don't mind saying that I don't quite understand that, but I'm sure that when you buy the machine and have the ROM to play with, then it will all make sense.

MIDI RESOURCES

MIDI, as I remarked earlier, was not implemented to a sufficient extent on the old DX7. Perhaps we were all supposed to buy KX88 master keyboards. Well we didn't, and we demanded more facilities - well, actually, other manufacturers provided more MIDI facilities and Yamaha had to catch up. Well, caught up they have and apart from the odd extra octave and keyboard split, most people are unlikely to need anything more capable than this instrument to use as a master keyboard. And by the way, I don't know how long Yamaha have been making pianos, but it's certainly taught them a lot about how to put together a synth keyboard. This must be as good as a non-weighted keyboard can get as far as playability goes. Going back to the MIDI aspects... System Set-up, which is memorised, consists of these possibilities:

- Transmission channel: 1-16 plus Off.

- Reception channel: 1-16 plus Off.

- Omni mode: On or Off.

- Local control: On or Off (determines whether playing the keyboard will make the internal tone generator sound or not).

- MIDI In control number: sets the MIDI controller number for the MIDI Controller functions which can be programmed with each voice.

- CS1, CS2 controller numbers: sets the controller numbers that will be transmitted by Continuous Sliders 1 and 2 via the MIDI Out. Also, sets the controller numbers that will control the voice parameters assigned to these sliders.

- Note On/Off: this can select whether the instrument responds to all MIDI note numbers or even numbers only, or odd numbers only. Useful for creating 32-note polyphony with two DX7S's.

- Program change transmission: can be selected to transmit MIDI program numbers as selected on the DX7S, or mapped according to a table of program numbers which can be user-defined or can be selected Off.

- Aftertouch transmission, On or Off.

- There are also System Exclusive messages which SysEx enthusiasts will find useful.

NICE?

Better than a slap on the belly with a wet fish, any day. With one or two tiny, tiny little exceptions, Yamaha have polished their already dazzling DX7 into near perfection. Non-DX owners can be assured that this is definitely a top person's keyboard and deserves a thorough investigation. Those who consider themselves anti-DX probably won't change their minds any. This synth is a lot quieter than the old one (practically no unwanted noise), but it still sounds 'thin and brittle', as they always say. Well, that's what DX synths are like, but they've got a hell of a lot going for them that other synths have not. Sheer variety of sounds, for one thing.

If you currently own a DX7 Mk1, here comes the bad news... The DX7S is much better, so I'm afraid you are going to have to sell up and upgrade. The DX7S is not a new synth, in the truest sense of the word 'new', but it's a lot more than a mere cosmetic rehash of an outmoded model.

Price (SRP) £1239 inc VAT.

Contact Yamaha-Kemble, (Contact Details).

Also featuring gear in this article

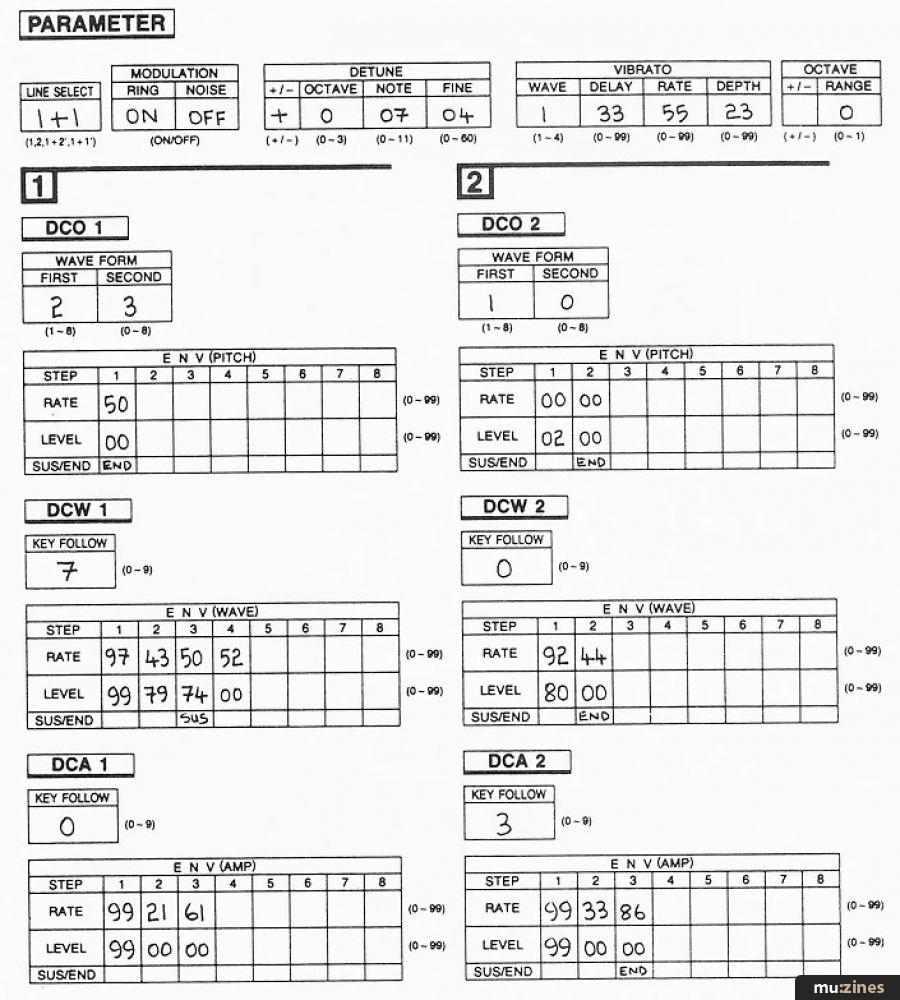

Patchwork

(MT Dec 88)

Patchwork

(MT Nov 89)

...and 1 more Patchwork articles... (Show these)

Browse category: Synthesizer > Yamaha

Featuring related gear

BeeBMIDI (Part 3)

(EMM Aug 84)

BeeBMIDI (Part 7)

(EMM Mar 85)

Hands On: Yamaha DX7

(SOS Dec 92)

Load Baring

(12T May 85)

Load Baring

(12T Aug 85)

One For The 7 - DX7 Patch

(ES May 85)

One Off - DX7 Patch

(ES Apr 85)

Pandora's Box

(MIC Oct 89)

Sight Reading - Yamaha DX7 Digital Synthesizer

(EMM Apr 85)

Steve Gray on the DX7

(EMM Dec 83)

Temperament

(MM Apr 87)

The Legend Lives On - Yamaha DX7IID

(SOS Mar 87)

The Right Connections

(ES Oct 84)

The Synths Of The Year Show - Synthcheck

(IM Dec 85)

Patchwork

(EMM Feb 84)

Patchwork

(EMM Mar 84)

Patchwork

(EMM Apr 84)

Patchwork

(EMM May 84)

Patchwork

(EMM Jul 84)

Patchwork

(EMM Aug 84)

Patchwork

(EMM Jan 85)

Patchwork

(EMM Feb 85)

Patchwork

(EMM Apr 85)

Patchwork

(EMM Jun 85)

Patchwork

(EMM Jul 85)

Patchwork

(EMM Feb 86)

Patchwork

(EMM Mar 86)

Patchwork

(EMM May 86)

Patchwork

(EMM Jun 86)

Patchwork

(EMM Aug 86)

Patchwork

(EMM Sep 86)

Patchwork

(MT Nov 86)

Patchwork

(MT Dec 86)

Patchwork

(MT Jan 87)

...and 19 more Patchwork articles... (Show these)

Browse category: Synthesizer > Yamaha

Browse category: Software: Editor/Librarian > Pandora

Publisher: Sound On Sound - SOS Publications Ltd.

The contents of this magazine are re-published here with the kind permission of SOS Publications Ltd.

The current copyright owner/s of this content may differ from the originally published copyright notice.

More details on copyright ownership...

Review by David Mellor

Previous article in this issue:

Next article in this issue:

Help Support The Things You Love

mu:zines is the result of thousands of hours of effort, and will require many thousands more going forward to reach our goals of getting all this content online.

If you value this resource, you can support this project - it really helps!

Donations for April 2024

Issues donated this month: 0

New issues that have been donated or scanned for us this month.

Funds donated this month: £7.00

All donations and support are gratefully appreciated - thank you.

Magazines Needed - Can You Help?

Do you have any of these magazine issues?

If so, and you can donate, lend or scan them to help complete our archive, please get in touch via the Contribute page - thanks!