Magazine Archive

Home -> Magazines -> Issues -> Articles in this issue -> View

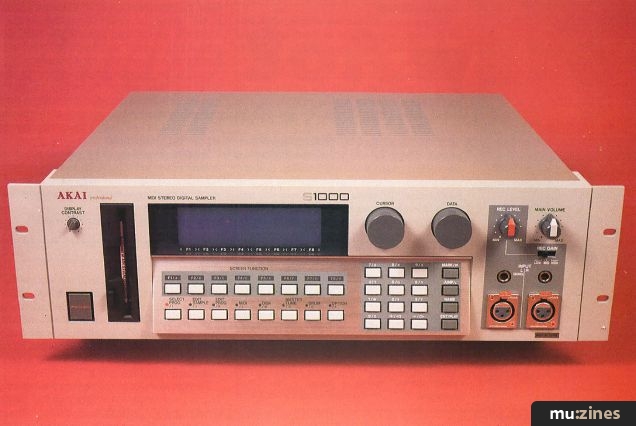

Hands On: Akai S1000 Sampler | |

Article from Sound On Sound, February 1992 | |

There's an S1000 in every studio — almost. David Mellor presents an introduction to this popular sampler.

There is one word I would like to say to you before I go any further: coherence. Say it out loud 20 times and brand it into you consciousness. I'll tell you why later, but for now let me cover just a little of the history of sampling. Once upon a time samplers were not just expensive, but horrendously expensive, and they had names like Fairlight and Synclavier. Then came a small and not terribly significant wave of samplers for ordinary folk which were affordable but not particularly capable. Then came the Akai S900. The S900 revolutionised sampling and was the first real sampler of the modern age. At the time it did just about everything you wanted a sampler to do, and more, and it was available at a reasonable price — not exactly cheap, but achievable for many people. I bought one myself straight after seeing it demonstrated at an exhibition. Later on in this series I shall be looking at the updated version of the S900, the S950. This now takes on a junior role in Akai's range and can be considered to be their entry level sampler.

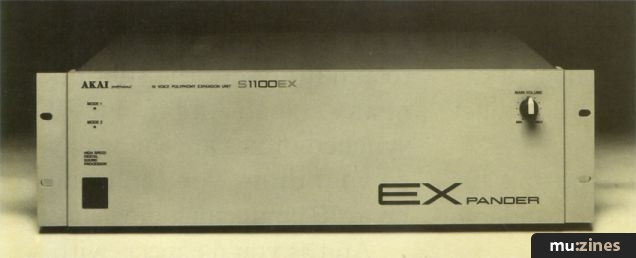

A couple of years after the original S900, Akai brought out what many people would see as the sampler perfected: the S1000. Although the S900 was very good, most users might have wished for a better signal-to-noise ratio, via 16-bit resolution rather than 12. Also, it was very inconvenient to combine programs to make the most of the inherent multi-timbral capability of sampling. A third difficulty was that the memory was fixed at just under 12 seconds at full bandwidth. 12 seconds seemed like Nirvana in 1986, but by 1988 it just wasn't enough, and with the S900 there was just nowhere to go. The S1000 answered all of these problems and added another bonus: stereo sampling. For most purposes, mono sampling is fine, but for certain applications proper stereo operation is essential. Now, Akai's range includes the S1100 which is basically an S1000 upgraded in terms of audio quality and with the inclusion of a digital effects section. In practice, the S1100 is so similar to the S1000 that an explanation of the differences is hardly necessary; an S1000 user will grasp it in a minute.

So what can the S1000 do? Well, in its standard form it can sample up to 12 seconds (actually just under 12) in stereo, or 24 seconds mono, with 16-note polyphony and 16-bit resolution at 44.1kHz. (The standard 2 Megabyte memory is expandable up to 32 Meg). In theory this should equal the audio quality of compact disc but in practice even the S1100 isn't quite up to this standard subjectively. The reasons for this are threefold, and if you think you can manage without this information then feel free to skip a paragraph.

Reason number one why 16-bit/44.1 kHz doesn't equal CD quality in any sampler is that you will nearly always be playing at less than maximum velocity. This brings the level down closer to the noise floor, thus reducing signal-to-noise ratio. Reason number two is that when you play several notes simultaneously, on average the signal-to-noise is degraded by 3dB for each doubling of audio channels, just like with a multitrack tape recorder. Reason number three is that, as with any piece of equipment in the real world, the S1000 isn't perfect, and that goes for the S1100 too. Akai have produced a brilliant piece of studio machinery, but other manufacturers have the edge in certain areas — but not in overall usability and range of features, in my opinion.

As always in the Hands On series, I am concerned with the basics of operation so that a newcomer to the S1000 can get started and get the thing to work at a basic level. As with every piece of equipment, there are features which you can manage without, and a few features which only the most dedicated experts will ever access. Don't ever worry about not being the master of any particular machine as long as you can get what you want out of it.

POWER UP

One problem that some samplers have which doesn't apply to the S1000 is losing the operating system. If the operating system is stored on floppy disk, and you don't have the disk, what can you do? Go down the betting shop and back a few nags probably, because your luck certainly can't get any worse. The S1000 has its operating system stored in ROM. This may not be the latest version of the system, which will be stored on a floppy disk nearby, hopefully, but it will get you going and provide very nearly all of the functions of which the unit is capable. If you do have the operating system disk, then just push it in the drive and switch the power on, and the newer system will load up automatically.

Assuming that the S1000 in question belongs to someone else, then you need to know something about how it is connected. You will notice the XLRs and jack sockets on the front panel. Surprisingly there are no inputs on the back, which one might think would be considered more appropriate for rack mount operation. If the inputs are straightforward — just use the jacks or XLRs according to the cables you have available — then the outputs are not so simple. The S1000 has a pair of main stereo outputs and eight other polyphonic outputs as well. It's ten to one that only the stereo outputs will be connected but 'power users' may have the individual outputs connected to separate channels on the mixer also. I would advise ignoring the individual outputs for the time being; they are useful, but let's not get too complicated just yet.

Figure 1. Programs In Memory page.

LET'S PLAY

First, let's load in a disk. Press the 'Disk' button, then the 'CLR' (Clear) soft key, then the 'Yes' soft key and the entire volume will be loaded. Press the 'Select Prog' button and you will see something like Figure 1. S1000 programmers follow two distinct strategies when building up their disk volumes so you will probably find yourself in one of two states.

Strategy 1: Each program will have a different program number, and all programs will be set to the same MIDI channel, probably channel 1.

Strategy 2: Each program will have the same program number, as in Figure 1, and they will all be set to different MIDI channels.

Multitrack tape users will probably follow strategy one, MIDI studios will undoubtedly follow the second option. If you have a 'Strategy 1' disk and you're a 'Strategy 2' person, then press the 'RNUM' soft key and operate the cursor and data knobs in the obvious way to set all the program numbers to 1. Don't forget to press the 'GO' soft key, or the renumbering operation will not be completed. Next turn to the Play Response page by hitting the 'RESP' soft key and set the MIDI channels as appropriate. You'll find that everything you want is available at a twist of the cursor knob, and that the data knob is there for selecting programs or setting parameters. To translate a '2' disk to suit a '1' user, follow a similar procedure. At this stage it's probably best to experiment with saving your newly modified volume to a blank formatted disk (a volume, as you might have guessed, is equivalent to the entire memory content of the S1000). I'm sure you can figure out how to do it.

SAMPLING

Manufacturers of samplers generally need a good talking to; they make you go through a major rigmarole to take a sample, when nine times out of ten you'll want to do it the way you always do it. Why not allow you to store on disk the standard working practice you will undoubtedly evolve? That would speed up operation tenfold. Still, as samplers go the S1000 is fairly easy to get the hang of.

First, press the 'Edit Sample' button to get to the Samples In Memory page where you will have to name your new sample before proceeding. If you plan on building up a library of samples then I strongly suggest that you adopt a scheme where each sample has a unique name. This is essential if you want to mix and match programs from different disks and use them in combination in the S1000.

"Akai have produced a brilliant piece of studio machinery in the S1000. Other manufacturers have the edge in certain areas, but not in overall usability and range of features."

My own scheme involves a three digit/letter code and a rough description of the sample, such as '1A1 BASS', "1A2 PIANO' etc., which is good for naming over 50,000 samples. Anyway, I digress...

To name the sample press the 'Name' key and type in a new name into the box provided. The forward arrow key acts as a delete key. Press 'ENT' to enter the name then press the 'REC1' soft key to move on to the next stage in taking a sample.

On the Record Setup page you will decide whether the sample is to be stereo or mono, and set the bandwidth and length, if you are sampling a series of sounds which require the same settings, then you don't have to adjust this page every time and you will progress straight onto the next stage by pressing the 'REC2' soft key. This is where it all happens: the main Record page. If you haven't adjusted anything I haven't told you to adjust then simply press the 'ARM' soft key and play your sample. Sampling will start automatically and end when the allocated time is up.

Monitor switching on this page is automatic (unless you decide otherwise). This means that when you enter the page you will hear through the outputs any sound coming into the S1000, until you initiate sampling and the process has run its course. This allows you to line up your source, and set the input and trigger levels. Take note of the graphic on the left of the screen and you'll figure this out.

When sampling is finished, then the monitor is switched off and the sample is available for play via the 'ENT/PLAY' button. If you wish, you can save the sample to disk at this point, but I usually don't unless I anticipate performing a crossfade loop. Although there is a slight risk of losing your sample, the time taken in saving really cuts into your sampling session. If I had been at the designer's elbow when this page was laid out I might have suggested the inclusion of a 'SAVE SAMPLE' soft key here (instead of the ridiculous 'METER OFF' soft key!). It's probably as well to mention at this point that although the basics are dealt with in these pages, I'm not covering everything there is to cover. Feel free to explore the manual for the details.

Figure 2. The Trim function.

TRIMMING AND LOOPING

You can reach the trim function by pressing the 'ED.1' (Edit 1) soft key. Figure 2 is what you will see. The graphic editing helps enormously in finding the correct start and end points. Just move the cursor to the Start and End fields and twist the data knob as necessary. You can zoom in or zoom out on the display to see the waveform better, but be aware that you can only see the beginning or the end of the sample, using the double arrow soft key. When you're done, press the 'CUT' soft key to get rid of the trimmings and release memory for further use. By the way, if you have been sampling in stereo then you will have noticed that it's just as easy as working on mono, and when you trim, although you can only view one side of the stereo at a time, both channels will be trimmed identically.

Trimming is very easy but looping, as with any sampler, is a pig. To be quite honest, I used to find crossfade looping easier with my old S900 than it is with the S1000. I found a combination of settings that worked almost always, but I haven't yet been able to find the equivalent for the more recent model. Anyway, press the 'LOOP' soft key and let's go.

Figure 3. Sample looping.

Figure 3 shows the Loop page. This time the waveform display is split into two, with a graphic on the right showing how well, or otherwise, the loops joins up. The aim is to get the ends of the two waveforms, at the point that they join, at the same level with the same slope. This should ensure a smooth loop. Here, you can move the end point of the loop (the 'at:' field), and its length ('lgth:'). Notice that by positioning the cursor carefully you can change the values in units, tens, hundreds and thousands etc., whatever is most convenient.

Once again, there's a silly feature on this page: you have to set in milliseconds the time you wish the loop to sustain for. I don't know of any application where anything less than forever, or at least until you release the key, will do. Just dial in a value of over 9999 milliseconds every time you want to loop a sample and try to be patient with a company which has got almost everything else right.

You will notice that there is a 'FIND' soft key, and this is an enormous help in finding a loop point. It doesn't work on both channels of a stereo sample, by the way. Stereo looping is possible, by accurately transferring loop values to the other channel manually, but it's difficult and time consuming to find an adequate stereo loop. Crossfading, unfortunately, is permanent and changes the sample data in memory. I find that most of the time the result isn't good enough, so it's essential to have a back-up on disk. I wish it could be retrieved more easily though.

One of the best points of the S1000 is that you can play the sample and adjust the loop points while listening to the results. With simple waveforms that don't need a crossfade loop, you'll set the loop points in no time at all with the help of this feature.

PROGRAMS

Let's suppose you have recorded a number of drum samples and you want to get them to play on different notes on your MIDI keyboard. Let's say that there are five different samples (not very ambitious considering the 200 sample capability of the S1000!). First things first: press 'EDIT PROG' to enter the Program Edit page. This page allows access via soft keys to further pages for creating keygroups and setting MIDI, output and pitch parameters. Since we have five samples, we'll have to create five keygroups, so go ahead and press the 'KGRP' soft key.

What you'll see at this point is a page containing quite a lot of information. Take the cursor to the end of the line which says "Change number of keygroups" and press the '+' button until the number of keygroups advances to five. For some reason, you can't add or delete keygroups by turning the data knob. The only other thing you need bother with on this page at the moment is the line, "Note-on sample coherence". Remembering my words at the beginning of this article, and think carefully before deciding whether or not to turn it on (all is explained in the box on coherence).

Figure 4. Setting the key span of the keygroups.

"Trimming is very easy but looping, as with any sampler, is a pig. To be quite honest, I used to find crossfade looping easier with my old S900 than it is with the S1000."

Now that we have five keygroups, press the 'SPAN' soft key. Now, as in Figure 4 (which only shows two keygroups), we can set the notes to which our drum samples will react. The easiest way to do this is, with a MIDI keyboard connected, to take the cursor to the 'LOW' note of the first keygroup and press the lowest key on the MIDI keyboard to which you want this keygroup to respond. The note will be entered automatically and the cursor will move ready for you to enter the next item of data. By doing this repeatedly you can set the MIDI keys for all the keygroups very quickly. Now we have the keygroups set up we shall assign some samples to them. Press the 'SMP1' soft key.

Figure 5. Allocating samples to keygroups.

Figure 5 shows the Sample 1 page with no less than four samples assigned to one keygroup. This is a bit over the top for our purposes, but let me assure you that unless you are editing an existing program then you won't be troubled by samples already present in the second, third and fourth zones ('zn' in Figure 5) so ignore them for now.

The default sample in zone 1 is 'SINE' which can be replaced by your first drum sample. Taking the cursor back up to the top of the page, change the keygroup ('KG') to '2', and make sure that you're only changing the parameters of one keygroup rather than all of them (set 'ED:ONE' rather than 'ED:ALL') and continue to enter the rest of your samples into the keygroups. Since these are drum samples, we had better make sure that all of them, apart from perhaps the open hi-hat, play all the way through to completion even from short trigger note. Go to the SMP2 page and set the playback type to be 'TO END', as necessary. Once all this is done, you can go back to the main screen via the SELECT PROG button and your program will be ready to play. It will be named 'TEST PROGRAM' at present, but I am sure you can figure out the program naming procedure (via EDIT PROG) easily enough. Remember always to save your hard work to disk before something happens that will cause you strife.

The S1100 is Akai's 'improved' S1000. It sounds a bit cleaner, has a useful extra Mix page, and a digital effects section, but in virtually all other respects operates just like an S1000 for straightforward sampling purposes. Virtually everything in this article about the S1000 applies to the S1100 too.

STEREO SAMPLING

If mono sampling is fun then stereo sampling ought to be twice as much fun, but you have to be aware of the best uses of stereo sampling. It's definitely good for drum sounds and for sampling loops from CD or record (by the way, to perform this type of looping, make the loop in the sequencer by repeatedly triggering the sample, rather than by looping in the sampler).

I find that stereo sampling isn't really much use for anything else. You can sample stereo synth voices, but it's a devil to create a good stereo loop, so most of the time I don't bother and just sample in mono. It saves tracks on the multitrack anyway! Getting back to drums and loops, stereo operation is very effective — but unfortunately the manual doesn't explain very clearly how to do it. Taking stereo samples and creating keygroups is exactly the same as doing it in mono, apart from a few details, explained below:

1) In the Record Set-Up page, set the mode to 'STEREO'.

2) In the Loop page, remember that the automatic loop finder only works on one channel at a time, although you can copy the settings to the other channel manually.

3) In the Sample 1 page of program editing, set Zone 1 to the left channel of your sample, eg. SAMPLE-L, and Zone 2 to the right channel, SAMPLE-R. Set the 'V-hi' of Zone 2 to 127.

4) In the Sample 2 page, set the pan of Zone 1 to L50 and Zone 2 to R50.

5) Go to the Keygroups page and set the coherence to 'ON'.

In a way, it's a pity that Akai haven't made more of a fuss about stereo sampling, and automated it a bit more to encourage the user. But when you know the procedure, you'll find that your stereo samples really do sound excellent, and that it's worth the extra bit of bother, in the right situations.

The Akai S1000, at the moment, is probably the world's number 1 sampler in terms of its range of features and user base. It won't always be, because there is always room for improvement, but in the meantime, if you want to be considered a sampler expert, then the S1000 is the machine to know.

Thanks to Sound Control for the loan of the S1000.

KEYS AND SOFT KEYS

COHERENCE

More with this topic

Sampling Keyboards |

Drum Fun |

Sample Shop |

A Vocal Chord (Part 1) |

Digital Mixing Magic - With Sampling Keyboards |

The Art of Looping (Part 1) |

Tuning Your Breakbeats |

Copycat Crimes |

What It All Means - Sampling |

The Complete Sampler Buyers' Guide |

Sampling: The 30dB Rule |

Photographing Sound - The Art of Sampling (Part 1) |

Browse by Topic:

Sampling

Also featuring gear in this article

Akai S1000 - Sampler

(MT Oct 88)

Akai S1000 - Digital Sampler

(MT Dec 88)

The New Standard? - Akai S1000

(SOS Nov 88)

Browse category: Sampler > Akai

Featuring related gear

Akai S1100 - 16-Bit Stereo Sampler

(SOS Dec 90)

Akai S1100 - Digital Stereo Sampler

(MT May 91)

Akai S1100EX - S1100 Expansion Unit

(SOS Sep 92)

Some Like It Hard - Akai S1100 Version 2.0

(SOS Jul 92)

Browse category: Sampler (Playback Only) > Akai

Browse category: Sampler > Akai

Publisher: Sound On Sound - SOS Publications Ltd.

The contents of this magazine are re-published here with the kind permission of SOS Publications Ltd.

The current copyright owner/s of this content may differ from the originally published copyright notice.

More details on copyright ownership...

Feature by David Mellor

Help Support The Things You Love

mu:zines is the result of thousands of hours of effort, and will require many thousands more going forward to reach our goals of getting all this content online.

If you value this resource, you can support this project - it really helps!

Donations for November 2025

Issues donated this month: 0

New issues that have been donated or scanned for us this month.

Funds donated this month: £0.00

All donations and support are gratefully appreciated - thank you.

Magazines Needed - Can You Help?

Do you have any of these magazine issues?

If so, and you can donate, lend or scan them to help complete our archive, please get in touch via the Contribute page - thanks!