Magazine Archive

Home -> Magazines -> Issues -> Articles in this issue -> View

Life In The Fast Lane | |

Korg M1 Music WorkstationArticle from Sound On Sound, August 1988 | |

As Korg prepare an armada of new products to invade the music shops, Tony Hastings investigates the M1 Music Workstation - the flagship that looks set to blow a lot of the competition out of the water.

As Korg prepare an armada of new products to invade the music shops, Tony Hastings investigates the M1 Music Workstation - the flagship that looks set to blow a lot of the competition out of the water.

The most important single factor that a keyboard can possess is good sounds. It doesn't really matter what it looks like or how many gigabytes of memory it has or whether it can replay Wimbledon highlights, if it doesn't sound good people won't buy it! I think the future of a new keyboard can always be judged by the 'Wow' factor; that's the kind of sound you make when you first hear it. Witness the remarkable 'Wow' achieved when the DX7 was first heard, and more recently how the D50 'Wowed' right off the scale.

The first thing I did after getting the M1 out of its box was to put the kettle on (it had been a long, boring drive to pick it up). Imagine my surprise when a 'Wow' out of all proportion came sailing into the kitchen. My wife had plugged the headphones into the M1 and started playing. "Wow Tony, this is GREAT! Come in here and listen to this." I went in, took the headphones and listened... She was right, it did sound great. And that was the last I got to hear of it for the next few hours as she merrily 'clunked' away on the keyboard, leaving me to read the manual.

FIRST IMPRESSIONS

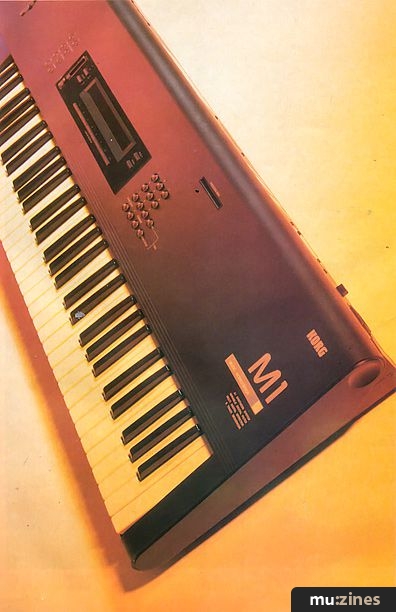

The M1 is a 5-octave digital synthesizer employing what Korg call AI synthesis. 'AI' stands for Advanced Integrated, which really means that you can combine different sound sources (samples, waveshapes, etc) together, along the lines of the Roland D50, Ensoniq ESQ1/SQ80 and Kawai K1. It's housed in a sleek matt black casing with rounded ends and a subtle wedge shape. It looks expensive and very classy; the sort of thing any hi-tech home owner would be proud to leave set up in the lounge.

The front panel is dominated by a large backlit LCD (like that of the D50) and around this are the control buttons. Even the buttons are interesting - raised circular shapes that light from underneath when selected. They are easy to see and add greatly to the futuristic styling of the whole keyboard. Also hiding deep inside is an 8-track sequencer, which I shall discuss later. Sound is output from any of four assignable separate output jacks on the back panel, which are alongside the MIDI In, Thru and Out, damper pedal, footswitch and headphone sockets. The internal operations are 16-bit and there is 4 Megabytes of waveform memory.

WOW!

If you've ever heard a Roland D50 you'll have a point of reference for the M1 voices, because of the similar nature of source samples used. First up are the Multi-Sampled waveforms which, although regarded as a single wave, are in fact several samples of the same sound taken at different pitches so as to overcome the dreaded 'munchkinisation' effect when replayed over different octaves. Then there are DWGS waves, which are computer generated to simulate standard (and not so standard) synth type waves. Finally, there are irregular waveforms created by extracting unrelated harmonic frequencies (good for bow scrapes, breathy attacks, noises etc).

In program mode you select a wave to edit (there are 100 to choose from). This wave can either be in Solo mode or you can combine it with another wave in Double mode, which reduces polyphony from 16 to 8 notes. Each wave may be edited separately and the second one can be timed to start later than the first and also detuned. From here the sound passes through a VDF (Variable Digital Filter) then a VDA (Variable Digital Amplifier) and, finally, through a digital effects section that permits two different effects at the same time, including echo, reverb, flange, chorus, EQ, distortion, exciter and tremolo. There is also a second section called 'Combi', which is used to set up combinations of the main program patches (100 in all) with different layers, splits etc. These can be edited, but only as to how they are set together, output assignments, effects and so on. You can't edit the waves directly from here.

Before we get too technical, let me describe the factory sounds supplied with the M1. They are rich, grand and sound very professional. The effects section is reasonably noise-free, although excessive settings do produce some background hiss. Unlike some keyboards, though, the untreated sound is generally excellent without added effects. The string/voice sounds are lush and have movement, the brass and reed sounds are very realistic, and the organs are lifelike and swirling. But I'm saving the best for last...

Not only are there wondrous special effects and breathy voices included but there is also a piano and a drum kit. Not just an average electric piano mind you, but a full multisampled grand piano (in different octaves) and a drum kit that is made up of clean, hard, modern drum sounds that would put many a drum machine to shame. These last two sounds are important selling points; the quality of the piano sound seems to be the deciding factor for many people when working out how good or useful a keyboard is. To have one available at the touch of a button, with no loading time, is great. The drums sounds, too, are nothing short of excellent and are an obvious inclusion to make the most of the onboard sequencer.

CREATING SOUNDS

The next step was finding out how to create great sounds for myself. Was the M1 going to be another case of 'preset blues', where the programming is so involved that you give up and just wait for new ROM cards to come along? I'd gleaned a very basic idea of how to edit the patches from my brief glimpse at the manual, so following the code of all brave and adventurous reviewers, I threw the manual to the crocodiles, swung down through the trees, and arrived at the Edit button unarmed and ready for action.

The first edit screen you arrive at is the OSC mode. Running along the bottom of the backlit display are eight cursor keys marked A to H. Pressing one of these moves the cursor to the corresponding display position above the button. From here you use the data entry slider or increment/decrement buttons to alter the value of the parameter at that position. A useful feature is that whenever the cursor is on a new parameter, that parameter title is displayed in the top right-hand corner, saving you the brain ache of trying to work out what the myriad of initials stand for next to each value.

On this first page you select whether the patch will be in Solo or Double mode (layered with a second wave). There are nine sub-pages for the second wave in Double mode, but selecting Solo means you skip over these. This is also where you set whether a patch is Poly or Mono and whether notes will Hold (ie. ignore any amplitude enveloping). 'Hold' is suited to percussion sounds that should play for their entire length. In this instance, I selected a Double sound which took me to the wave selection page for OSC 1. Here you step through the 100 available waveforms until you find one that you want to use. Move the cursor to the right and you can set the volume for this wave within the patch and also its pitch in octaves (4, 8 or 16). Following this is a similar screen for selecting the second wave to be played. Along with the pitch and volume parameters are three more functions for setting the pitch interval between the waves (+/-12 semitones), a fine detune value (+/-50), and the start time of the second wave in relation to the first (up to +99).

Next are two screens for the OSC1 and OSC2 waves that allow you to control the pitch of the sound with an envelope generator (Pitch EG). I'm not going to describe every single function on every page as much of it is familiar territory. Suffice to say, using an ADSR-type curve, you can have the pitch for each wave moving in different directions throughout the time you hold a key down (and release, of course). Using a wave that isn't too reliant on pitch for the second wave and making it sweep around the first can be very effective and eerie.

So far, editing has been very quick and easy; you see a button, press it, and listen to the result. This brings us to the VDF (Variable Digital Filter). There are four screen pages of parameters here for wave 1 and four for wave 2. The first allows you to set the filter cut-off (the smaller the value, the more muffled the sound), along with the intensity of the envelope generator. The next VDF EG screen allows for very comprehensive settings of attack time/level, decay time, break point, slope time, sustain and release level, and release time. Not content with that, Korg have quite rightly noted that many sounds contain fewer high frequencies when played gently, and so they have included a velocity envelope to enable you to control the filter cut-off (brightness) with your playing style. The last of the four filter screens sets up the keyboard tracking, allowing you to modify the brightness of notes according to their position on the keyboard. Again, this is a very detailed envelope with control over the cut-off by time, position, and ADSR.

Overall, this is a very detailed filter section, giving the programmer great depth to work with when moulding a sound without being over-confusing or difficult to work with. The digital filter is clean and quiet but I did miss a 'Q' or resonance control, as found on most analogue synths.

The next three screens concern themselves with the digital amplifier (VDA). The first covers the VDA EG which, like the VDF EG, has attack time/level, decay, break point, slope and release time for shaping the volume of the sound over a given period. The second screen lets you shape the volume by using keyboard velocity as the controlling factor. Interestingly, if you choose velocity values for the first wave that are opposite to those of the second, you can achieve a velocity crossfade between the two sounds. The final screen gives you control over note amplitude as determined by key position.

As with the VDF, I found the signal path easy to follow and editing was simple and straightforward. There is no LFO as such on the Korg M1, instead it uses two more envelopes to modulate the pitch (for vibrato effects) and the filter cut-off (for 'wah-wah' type effects). Both these have the same envelope parameters, with a choice of waveform for the modulator, frequency of modulation, delay, and intensity. In addition, you can modulate either or both of the OSC waves and select whether modulation sync is on (re-triggering with each new note).

The last two editing screens concern themselves with the aftertouch modulation and joystick control. Aftertouch can be set to modulate or change Pitch, Pitch MG (LFO of pitch), Filter Cut-off, VDF MG (LFO of filter), and the Amplitude of the patch. The joystick can be assigned to control six parameters - Pitch Bend (+/-12 semitones) and Filter Cut-off on the left-to-right axis, Pitch MG and Intensity on the upward axis, and VDF MG on the downward sweep.

EFFECTIVE PROGRAMMING

As I stated at the beginning of the review, there is a two-channel digital multi-effects unit built into the M1 and the sound that you have been editing can be routed through it in a number of ways. Each effect is stereo and has two assignable input channels: A and B for 1, C and D for 2. They can be run in parallel or serial (ie. chained) and the enhanced signal is sent to outputs 1/L and 2/R. In serial mode, OSC wave 1 passes through effect 1 and OSC wave 2 passes through effect 2 (assuming you have a second wave). In addition, wave 1 also passes through effect 2, either on its own or combined with wave 2 if you are in Double mode. In parallel mode, waves 1 and 2 pass through their respective effect individually.

Korg have been more than generous with the effect programs; there are no less than 33 different ones (including groups of reverb, delay, chorus and flange). Among the more interesting effects are Distortion/Overdrive (great for guitar and that old Deep Purple Hammond sound), Symphonic Ensemble (much bigger and grander than chorus), Rotary Speaker, and Exciter (for adding that presence that really cuts through). Programming the effects is easy - you simply select an effect and then adjust its main parameters (mix, EQ, etc) until it does what you want. This has got to be the most versatile effects section on any synth to date and has many more features than a lot of full-blown rack effects! Take it from me, there is just about any effect combination here that you might want.

Sound creation on the M1 is a doddle, and so intuitive that anyone with even the most basic experience of a synth could generate good sounds without constantly referring to the manual. The editing process has been kept very simple, and the inclusion of a Compare button means you can keep referencing back to the original patch.

Whilst on the subject of editing, Korg have provided eight parameters that are editable in real time whilst in play mode. This shows that Korg have worked hard not only to design an extremely modern keyboard but also to produce a performance-oriented synth with features that hark back to the analogue days of 'knob twiddling' (excuse the rather dubious but descriptive phrase). Each time you select a patch there are eight functions available along the bottom of the main display that let you change the value of any or all of the following: OSC Balance (between two waves in Double mode), Filter Cut-off, VDA level, Keyboard Tracking, Velocity Sensitivity, Attack time, Release time, Effect Balance.

M1 SEQUENCER

Time now to look at the other major feature of the M1, the built-in sequencer. This is an 8-track affair that can trigger internal voices, external sources (via MIDI) or both. There are 10 songs, 100 patterns and two blocks of memory available for sequencing. The default memory block is 4000 notes when using 100 patches and 100 combinations, but this may be increased to 7700 notes if you are prepared to reduce patches and combinations to a maximum of 50 apiece (even when you're just in play mode).

Three modes of recording are available: real-time, step-time, and pattern recording. The M1 always defaults to real-time recording, so let's start with a look at that.

Pressing the SEQ button moves you straight to the real-time record page, where you must first choose which song to record (0 to 9). Having chosen a song it's then necessary to initialise it. This process is needed to clear any previous data in the song and to set the time signature for the piece (you only have the choice of 2/4, 3/4, 4/4, 5/4 or 6/4). You then select a track, followed by the initial measure (bar) on which to start recording. A program/patch number needs to be chosen for the track, but you may change patches during the sequence to bring in different sounds on the same track if you wish. You can also set the track volume as well as tempo; the latter can be altered in real time as the sequence is recording.

MAKING TRACKS

SEQUENCER FEATURES

Real-time, Pattern and Step-time input modes are available, with punch-in/out editing in real time. Up to eight tracks of information may be simultaneously recorded from an external sequencer or drum machine.

Each track has its own pan, volume, transpose, detune and track protect setting. Sequence tempo can be varied as you record. 100 patterns and 10 songs can be saved internally or to an optional RAM card. Other functions include Copy, Add, Delete, Insert and Erase of information. Tracks may be bounced together but the source track always takes on the same MIDI channel and sound as the destination track.

Having got to this point, I decided the time was ripe to run the sequencer through its paces and start recording some drums as the first track. I pressed the REC button then the START/STOP button and heard nothing... The metronome wasn't turned on! After hunting through the manual I discovered how to turn it on and set the resolution. The latter, in fact, is a form of pre-record note quantisation which, if left set on 48, should give you what amounts to quasi real-time (unquantised) recording.

Back to the recording and I now had a click to play to. I allowed two bars of this and then played four bars of drums. I had to quickly hit the STOP button when I finished, as you don't specify an end measure in this mode. My timekeeping (like most sequencer users) is fairly ropey so I tracked down the Quantise screen.

Here you are able to choose which track and which part (by setting the first measure and number of measures after it) you wish to have corrected. You can specify a note resolution of 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, 16, 24 and 48, and choose whether to quantise note data, controller data, or both. I pressed the button marked 'EXECUTE', and after an 'Are you sure?' message the deed was done.

I replayed the track and, to be honest, it felt a little strange. I had chosen a quantisation value of 8ths and ropey though my playing was, the beats weren't more than an 8th out, yet I could distinctly hear a little flamming against the metronome. So I played the part again and selected Quantise again. The resolution value had jumped back to 48ths again (I wish it would stay at the last value used) so I reset it and acknowledged the prompt once more. It's a shame there isn't a way of auditioning the quantisation so that different values can be experimented with before committing yourself to something that might not be right.

Still, time to soldier on with the next track, which I set for bass guitar. After the two-bar count-in I played along with the drum part already there. Surprise, surprise. The sequence carried on recording after the drums finished. I had been so used to sequencers that use the first track to set the length for the pattern that I had forgotten this was 'real-time' recording and that any track can be any length. Instead of re-recording I looked for the Edit page, discovered you could add, delete or erase measures and so chopped off the extra measures on the bass track that I didn't need.

So far so good, but how about repeating these bars to save myself the effort of playing them again? Easy - just go to the Measure Copy page and specify the source track/measure and the destination track/measure.

By now I was feeling a little frustrated with real-time recording and thought it would be good if I could actually specify where to start and stop recording. On further inspection of the manual I happened on the punch-in/out facility, which allows you to specify a record-start and record-stop measure. Having specified measures 8 to 12, I started the sequence and recorded four bars of piano.

Now I decided to try my hand at pattern recording as I felt this might be more suited to my style of sequencing. As with starting a new song, each pattern must first be initialised. This is so you can specify how long it will be (eight measures maximum) and give it a time signature. The pattern will always play the sound that you were using for the last track in the real-time record page. If you want a different sound you must go back to that original page and either select a new track or set another sound for that track. I worked hard with the pattern system for a while and discovered a few disturbing things.

First of all, you can only record one track for each pattern. This may not sound too bad until you realise that you can't hear any other parts playing whilst recording your pattern; you have to record each part 'blind' and combine them at a later stage. Secondly, although 100 patterns sounds like a lot, it isn't. If you use one pattern for each track (8), and if the average song has four different parts, you will have used up 24 patterns (4x8) on one song - almost a quarter of your available patterns.

The point behind pattern recording is that you can save large dollops of memory by having your commonly used parts stored as patterns and then just repeat the patterns rather than use up note memory. The M1 will let you copy a pattern to a track as 'play data', which means that what you played in the pattern is copied not the pattern itself, thus freeing up the pattern. But this is a vicious circle that eats up note memory, and when you've only got a maximum of 7700 notes to start with, it's silly.

A more sensible feature is that the pattern repeats in overdub mode (like a drum machine), so you can keep adding new bits. There is also the facility for erasing specified notes, or the complete works. This is useful for experimenting with different parts without having to start the whole recording process over again.

STEP-TIME ENTRY

Having experimented at great length with the real-time recording aspects of the M1 sequencer, I checked out the step-time option. Here I felt a little more at home as, by the very nature of step-time recording, many of the procedures are fairly standard.

You choose the note value for the note you wish to input (from a 32nd to a whole note) - specifying a triplet or dotted note if required - and the dynamic value desired, using music theory terminology (from ppp, which is equivalent to a MIDI velocity of 24, up to fff, which is 114). You can input chords as well as single notes and there are two buttons used to input rests or ties, plus a back-step option if you change your mind. Across the top of the display is a readout of the current measure/beat and clock.

In the main mode you keep recording notes until you wish to stop. It's as simple as that. The results are accurate and there is, of course, no need to quantise. You can also record in exactly the same way in step pattern mode, where you initialise a pattern and use it to input note data, the only difference being that at the end of the pattern it repeats itself in overdub mode until you press STOP. What more can I say? Step-time works well and if that's the way you like to record then you've got no problems.

LITTLE EXTRAS

There are a few other features of the sequencer that are worth noting here. Tracks can be copied or bounced (bounce will erase the source track as it copies) but doing so does not combine patch and MIDI information - your source track will end up playing with the same sound and on the same MIDI channel as the destination track. Each track can have its own individual volume, transposition, detune (for minor adjustment of tuning), pan to any of the four audio outputs, and a track protect to stop you erasing it by mistake.

One clever implementation is multichannel recording; setting each track to a different MIDI number that matches incoming MIDI information (from another sequencer or drum machine) enables you to record up to eight external parts at the same time.

The last section of the sequencer concerns the effect channels. Yes, we're back to the effects again! There are only two effect channels but eight potential sounds playing at the same time when in sequence mode. So the effects that form part of each patch are stripped away and you are left to assign new effects to the overall combined audio output of all eight tracks.

MOANS & GROANS

After working with the M1 for a short while a few things came to light which I feel I must point out.

To start with, I'm not that impressed with the sequencer. It could have been great but instead ended up being pretty average. It has many clever and useful features that somehow get lost in the overall clumsiness of its operation. A bit like some fast food chains, attractive and inviting but leaving you a little unfulfilled. Anyone with no experience or only basic experience of sequencers would find this one confusing and difficult to come to terms with. The manual doesn't help either. Although crammed full of diagrams explaining all the functions, it leaves the reader to extract the information more by trial and error. A sophisticated instrument like this needs a manual that takes you by the hand and leads you through the operations, so that you feel in control at every stage.

Korg are still using their joystick design for modulation and I think this is a mistake. I find it too 'light' and fiddly for serious onstage mid-gig 'waggling' (although you may disagree and love the feel of it). It is also just the right height to get snapped off as it protrudes so far from the casing.

But for me, the real annoying point is the lack of a disk drive. Korg are marketing this product as a 'Music Workstation' yet the maximum amount of storage space for your sequences is only 7700 notes, and the only external storage medium (apart from System Exclusive dumps) is a RAM card costing £89. There isn't even provision for dumping to tape. A great many people who buy the M1 will no doubt be based at home and this may well be their only or major keyboard. So where are they going to store their sequences?

A true music workstation should provide a system that is independent of any peripherals so that everything (except singing) can be accomplished in one box. Had there been a disk drive, the 7700 note limit would have been no problem as songs could have been stored quickly and cheaply on floppy disk for further use. Those of us lucky enough to own keyboards that receive System Exclusive dumps and have a built-in disk drive are a bit better off. However, I really do think it's short-sighted of Korg, especially as the Roland D20 has both a sequencer and disk drive, and is £300 pounds or so cheaper!

CONCLUSIONS

Now that I've got the moans out of the way I must say that I still think the Korg M1 is destined to be big, VERY BIG. The sounds are sensational, and the provision of a PCM card slot means that you can keep updating your source samples thus keeping the M1 one step ahead all the time. No longer will you be stuck with variations on the same theme, as Korg (and presumably third party developers) provide new and original samples to add to your library. The perfect hybrid synth/sampler maybe?

It's been a while since I got this excited about a new synth, and that goes for everyone I've spoken to who has heard it. I think the M1's strengths far outweigh the moans I've made here, but as a potential purchaser you should be aware of them. Having said all that, if you treat the 8-track sequencer as a fairly extensive musical notepad (but with limited storage) and concentrate on the fact that the M1 outperforms anything else currently on the market (although that is a brash statement given the speed with which new products appear), then you won't be disappointed. There are features that I haven't had the time or space to cover in detail, like the facility for using different scales (including your own), but the essential operations have been covered. Check it out if you can find one. But you'd better hurry!

Price £1499 inc VAT.

Contact Korg UK, (Contact Details).

Also featuring gear in this article

A Beginner's Guide to Korg's AI Synthesis

(SOS Apr 90)

Hands On: Korg M1

(SOS Mar 92)

Korg M1 - Music Workstation

(MT Jul 88)

Patchwork

(MT Jun 89)

Patchwork

(MT Aug 89)

...and 2 more Patchwork articles... (Show these)

Browse category: Synthesizer > Korg

Featuring related gear

Double Dutch SAM1 - Sample Expander For Korg M1

(SOS Nov 92)

Korg M1R

(SOS Jul 89)

Pandora's Box

(MIC Oct 89)

Browse category: Sampler (Playback Only) > Double Dutch

Browse category: Expansion Board > Cannon Research

Browse category: Expansion Board > InVision

Browse category: Synthesizer Module > Korg

Browse category: Software: Editor/Librarian > Power Tools

Browse category: Software: Editor/Librarian > Pandora

Publisher: Sound On Sound - SOS Publications Ltd.

The contents of this magazine are re-published here with the kind permission of SOS Publications Ltd.

The current copyright owner/s of this content may differ from the originally published copyright notice.

More details on copyright ownership...

Review by Tony Hastings

Help Support The Things You Love

mu:zines is the result of thousands of hours of effort, and will require many thousands more going forward to reach our goals of getting all this content online.

If you value this resource, you can support this project - it really helps!

Donations for November 2025

Issues donated this month: 0

New issues that have been donated or scanned for us this month.

Funds donated this month: £0.00

All donations and support are gratefully appreciated - thank you.

Magazines Needed - Can You Help?

Do you have any of these magazine issues?

If so, and you can donate, lend or scan them to help complete our archive, please get in touch via the Contribute page - thanks!