Magazine Archive

Home -> Magazines -> Issues -> Articles in this issue -> View

Summers | |

Andy SummersArticle from One Two Testing, May 1984 | |

A chorus line or two

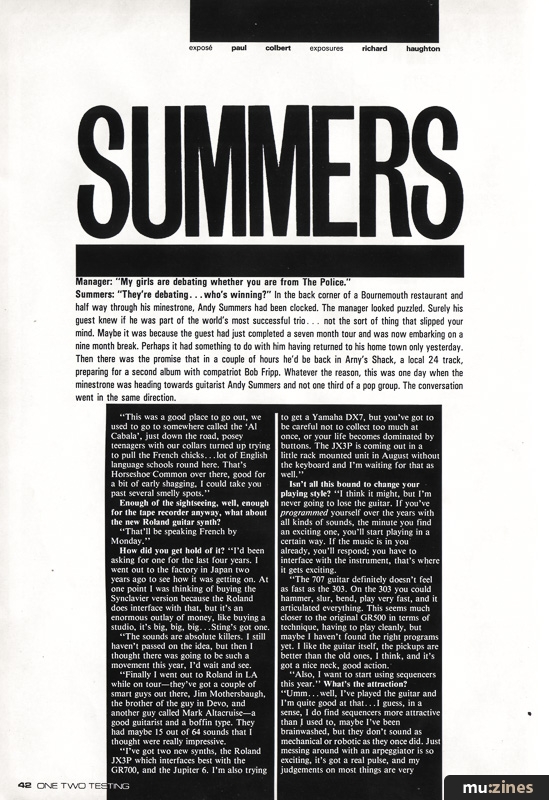

Manager: "My girls are debating whether you are from The Police."

Summers: "They're debating... who's winning?"

In the back corner of a Bournemouth restaurant and half way through his minestrone, Andy Summers had been clocked. The manager looked puzzled. Surely his guest knew if he was part of the world's most successful trio... not the sort of thing that slipped your mind. Maybe it was because the guest had just completed a seven month tour and was now embarking on a nine month break. Perhaps it had something to do with him having returned to his home town only yesterday. Then there was the promise that in a couple of hours he'd be back in Arny's Shack, a local 24 track, preparing for a second album with compatriot Bob Fripp. Whatever the reason, this was one day when the minestrone was heading towards guitarist Andy Summers and not one third of a pop group. The conversation went in the same direction.

Image credit: Richard Haughton

"This was a good place to go out, we used to go to somewhere called the 'Al Cabala', just down the road, posey teenagers with our collars turned up trying to pull the French chicks... lot of English language schools round here. That's Horseshoe Common over there, good for a bit of early shagging, I could take you past several smelly spots."

Enough of the sightseeing, well, enough for the tape recorder anyway, what about the new Roland guitar synth?

"That'll be speaking French by Monday."

How did you get hold of it?

"I'd been asking for one for the last four years. I went out to the factory in Japan two years ago to see how it was getting on. At one point I was thinking of buying the Synclavier version because the Roland does interface with that, but it's an enormous outlay of money, like buying a studio, it's big, big, big... Sting's got one.

"The sounds are absolute killers. I still haven't passed on the idea, but then I thought there was going to be such a movement this year, I'd wait and see.

"Finally I went out to Roland in LA while on tour – they've got a couple of smart guys out there, Jim Mothersbaugh, the brother of the guy in Devo, and another guy called Mark Altacruise – a good guitarist and a boffin type. They had maybe 15 out of 64 sounds that I thought were really impressive.

"I've got two new synths, the Roland JX3P which interfaces best with the GR700, and the Jupiter 6. I'm also trying to get a Yamaha DX7, but you've got to be careful not to collect too much at once, or your life becomes dominated by buttons. The JX3P is coming out in a little rack mounted unit in August without the keyboard and I'm waiting for that as well."

Isn't all this bound to change your playing style?

"I think it might, but I'm never going to lose the guitar. If you've programmed yourself over the years with all kinds of sounds, the minute you find an exciting one, you'll start playing in a certain way. If the music is in you already, you'll respond; you have to interface with the instrument, that's where it gets exciting.

"The 707 guitar definitely doesn't feel as fast as the 303. On the 303 you could hammer, slur, bend, play very fast, and it articulated everything. This seems much closer to the original GR500 in terms of technique, having to play cleanly, but maybe I haven't found the right programs yet. I like the guitar itself, the pickups are better than the old ones, I think, and it's got a nice neck, good action.

"Also, I want to start using sequencers this year."

What's the attraction?

"Umm... well, I've played the guitar and I'm quite good at that... I guess, in a sense, I do find sequencers more attractive than I used to, maybe I've been brainwashed, but they don't sound as mechanical or robotic as they once did. Just messing around with an arpeggiator is so exciting, it's got a real pulse, and my judgements on most things are very instinctive and sensual."

They've also reached the stage where they can be 'mistreated' and will react it.

"Abused, yes, there are ways of playing that will produce different effects. I bought a Sequential Circuits Six-Trak, and that's fantastic, so much fun."

You seemed to be playing around with sequencers on "Synchronicity", particularly the first track, "Synchronicity One".

"That's an OBX, Sting did that. He was the first of us to get into this area, that's why he got the Synclavier. Live we also used the Oberheim on 'Wrapped Around Your Finger', a little synth line, and 'King of Pain'. The main problem is trying to stay in time with them.

"Stewart linked a drum box to Sting's sequencer so he could stay in time with that and we could all hear the drums. Only one night in seven months did we go out. On 'King of Pain' I played the guitar break right the way through and it sounded slightly weird, then when we came back in we were one bar out.

"In terms of writing and keeping ideas, like most musicians do, I have a library of tapes – now I always try to keep the guitar in concert pitch and tell the tape recorder what I'm playing, otherwise you can never remember what you've done when you come back to it. The tapes are filed – the 'kitchen series' for instance. If there's a day when the inspiration isn't immediately there, you can idly flick through them."

Do the best ideas come when you've just sat down to play, or when you've been at it for four or five hours?

"I think generally the best ones come in a brief burst when you're not expecting it. Otherwise, through sheer persistence, you might work on one song and finally you're in between coming back to the chord progression for the fiftieth time and you wander off and do something else, and that's the one that works."

But how do you function under pressure when the studio time is ticking away?

"Well, we can be more indulgent these days and take more time. I can stop and wait, and maybe two weeks later the moment will present itself. You have to be very aware of the serendipity aspect of music."

However miserable and uninspired you may be, you have to retain the confidence that in a couple of hours, or days, you'll be able to do something better.

"If you've spent enough years doing it, you'll know that you WILL be a channel for something great, you just have to wait.

"With the last Police album there were moments like that. We did it in two sections, recording at Montserrat, then mixing in Canada. It was only after we'd tak« a week off and started hearing it back in Canada, almost for the first time, that we realized it was good. When you're recording there's this terrible, terrible doubt that goes through your mind – 'we just can't do it anymore'. It's unbelievable. Then you finally come out of the studio and the whole thing begins to assume a life and identity of its own. If you carry on working in a creative medium you become a bit kinder to yourself – 'it's not the end of the day; that wasn't the greatest piece I've ever written, but I'll do another'."

So it's a question of faith; knowing that however poor it seems at the time, that feeling is an unbalanced view?

"Yes, but I've found that playing music and having played it all my life, your psyche is so bound up with it, you feel depressed, hopeless, worthless as a human being if your performance is poor. I've always been dictated by my current playing mode... whether it's up enough, or whatever. Normally I'm at my happiest, generally, in life when I'm into it and I feel I'm justifying my existence because I'm really playing well."

But should you be discounting the rest of your life because your playing is bad on one day?

"No, it's a terrible thing to do. That performance is so small compared with everything else in your life, but where does this stuff start? When I was 14 I didn't know this was going to happen. By the time I was 17 I was locked into it, feeling up or down."

So who do you feel answerable to in a performance?

"Me, really, more than anyone else. The audience usually think it's great – there's the build up, the spectacle, the rest of the band. But they're going 'yeah, great' and you could be thinking it's the worst you've ever played.

"But it's always yourself that you have to live with. If you're any good, that's the way it is – painful. Nobody can console you. You get over it.

"On a seven month tour you start off well; lots of energy, you're glad to be back. Then it tails off and you're into 'the tour' and you get out of your paperback to go on stage... you always try but some nights you're just too tired, it's the same old songs. Occasionally, in the middle period, you get a really good one, then towards the end it picks up again. You can see the end in sight, it frees you, you don't care as much, and you play better.

"You can't be the same for every gig. It can't be magic every night."

No, because then, by definition, it wouldn't be brilliant, those magic nights have to stand above all the others.

"Absolutely, that's right, you never come to rest, you just hope that some of the great nights have been recorded. I don't think our best ones have been."

Apart from unique gigs, what about historical equipment – the greatest buys and acquisitions you can remember; those that inspired you to play better?

"Let's think. The Cry Baby wah-wah, that took the guitar up a notch, the MXR Phase 90 was another. I was very hard pushed to pay for a Phase 90 but you HAD to have one, I think I've still got it. The Mutron 3 auto-wah is incredibly good, they never really caught on, but I love to play about with it at soundchecks. The octave divider is good as well.

"What else... tell me some units... er, oh the Echoplex I suppose, and the old Fender Concert Series amps have the most incredible vibrato units. I've never heard anything to equal the richness of those.

Can the right equipment produce great moments in the studio?

"Usually you get one element that starts the magic working and pulls everything else in. Something like 'Deathwish' came out of the sound of the guitar with the Echoplex. We were fooling around, couldn't really make it work, then I switched on the echo and started this repeat going, working over a D. Then I found certain pull-offs in the scale were really working, and the track suddenly started to form itself.

"'Walking On The Moon' grew up in a similar way. We started to play with the echo, and suddenly the drums were right, the bass line fell into place... it's like playing live on stage. You have to try to get that in the studio."

What about the '61 Tele?

"I got that for 200 dollars, I was teaching in California at the time and I said to the guy, 'I don't know why you sold it, it's an incredible guitar.' He didn't really like it, but to me it's the best guitar I've ever had.

"It's not as good as it used to be. There was a strange accident one night in Boston Gardens. The guitars were backstage – Sting's Fender bass and my Telecaster. We've never figured this out, but they must have been near a strong magnetic field because the back pickups on both guitars went completely dead before we went on stage. They both died, nothing left in them, as everything had been sucked out.

"I had to have the guitar remagnetised, but when I got it back, it was extremely bright. Time changes the sound of a pickup. It's slowly returning to the way it was.

"The Steinberger bass was great though Sting now uses some white Duane Eddy sort of thing that sounds a bit twangy to me. I've got some nice guitars at home... a 175, a 335 and '61 Strat which is wonderful, and a Les Paul Junior and those are it, really. I'm a traditionalist as far as guitars go."

Do you get dissatisfied with modern guitars?

"Yes, they don't last long. I'm the bane of modern guitar makers. You go into a store, especially in America, and they turn out of the woodwork... 'try this, try this', and they're all the same.

"It's not so much the feel but the sound of the pickups that kills it for me. You either get those dreadful, heavy distorted things – DiMarzios – or something duff. I explain that I want middle with edge, but it's mostly middle they lack. You get up the top and there's this thin, screechy little sound. I want something fat. I want a note you can walk across. It's difficult to work out whether I'm an incredible snob about it, or if there genuinely is something there. I always try to find some mystical reason why the old guitars tend to be better."

Do you think the next generation of guitar players will know what it's missing?

"Well, look at, say, Eddie Van Halen. He's playing old guitars, old Strats. He's excellent, a great player."

Have you seen anyone else you've liked recently?

"I tell you one guy I did see who knocked me for six, the only one, actually. He's called David T Walker. I saw him in Chicago with the Crusaders. He's a strange, tall, black guy with glasses, looks like a professor and I think he plays with his thumb. He's got this wonderful, warm bluesy style, so musical.

"As you play more you can see so fast when something's happening. Julian Bream is like that, and Segovia has it, he manages to shrink an auditorium so it's you and him, and you're right in front of the soundhole.

"When I studied classical guitar, I'd buy records of standard pieces but by different players, and the greatest interpretation was always Bream's. He made the most sense out of the music and found the character hidden at the heart of each piece.

"So much of that is lost in modern playing. I feel sorry for young players. By the time they're 18 or 19, it's supposed to be happening for them. There's no time to grow or develop before you're exposed and expected to be great."

You've got that opportunity, so how do you see your own playing progressing?

"Or disgressing, or regressing, who knows. Doing something that moves people becomes more important and that doesn't necessarily come from having more licks. I've gone past that. I've gotten about as good as I'll ever be, which is not very good.

"I think you start to draw from other sources which colour your whole outlook. I keep practicing. I practice quite a lot, playing my scales, keeping the chops up, otherwise it would definitely go away. I'm not a natural guitar player. I have to work at it.

"I'm looking forward to playing a lot this year. There's this album with Robert, and I had a lot of serious conversations with Jack de Johnette. I'm sure we can do something together, an album maybe, or a week at the Village Vanguard in New York with a bass player.

"I'm also working on a film score. Then the only next major project would be, I guess, to make a genuine solo album with songs and things. I could never do a straight pop album. I think I'm too old to launch myself as a pop star outside of the Police, and besides, why bother? I'm already doing that, I'm on MTV every five fuckin' minutes as it is. What's the point?"

Answer the manager's question, Andy.

"Well... yes, I am."

More with this artist

Summers' Coming (Andy Summers) |

More from related artists

Stewart Copeland (Stewart Copeland) |

Stewart Copeland (Stewart Copeland) |

Stewart Copeland (Stewart Copeland) |

The Lore of the Jungle (Stewart Copeland) |

This Is Gordon Sumner (Sting) |

African Rhythms (Stewart Copeland) |

Sting in a Tale (Sting) |

Sting (Sting) |

Logical Progression (Stewart Copeland) |

Publisher: One Two Testing - IPC Magazines Ltd, Northern & Shell Ltd.

The current copyright owner/s of this content may differ from the originally published copyright notice.

More details on copyright ownership...

Interview by Paul Colbert

Help Support The Things You Love

mu:zines is the result of thousands of hours of effort, and will require many thousands more going forward to reach our goals of getting all this content online.

If you value this resource, you can support this project - it really helps!

Donations for January 2026

Issues donated this month: 0

New issues that have been donated or scanned for us this month.

Funds donated this month: £0.00

All donations and support are gratefully appreciated - thank you.

Magazines Needed - Can You Help?

Do you have any of these magazine issues?

If so, and you can donate, lend or scan them to help complete our archive, please get in touch via the Contribute page - thanks!