Magazine Archive

Home -> Magazines -> Issues -> Articles in this issue -> View

The Dynamic Duo | |

Article from Sound On Sound, February 1986 | |

Yamaha smash new price barriers with their latest FM synths - the DX100 and DX27. Mark Jenkins assesses their performance as stand-alone keyboards and as compact MIDI expanders.

Yamaha have smashed new price barriers with their latest FM synthesizers. Mark Jenkins assesses their performance as stand-alone keyboards and as compact MIDI expanders...

Just when you thought it was safe to go back into the waters of budget synthesis, Yamaha have turned the market on its head (again!) with two new synths derived from their recently-launched DX21.

In fact, some recent DX21 purchasers may well be annoyed by the launch of the new models, albeit with very little justification - the DX21 is a little more powerful than either, but at £699 it's clearly in a slightly higher price bracket too.

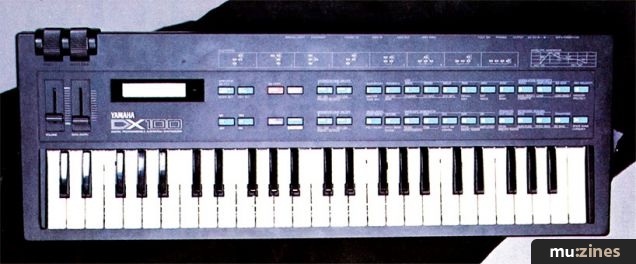

However, the DX21 is a good starting point for understanding the two new models, which have practically identical specifications other than in the details of packaging. The DX27 has five octaves of standard keys and the DX100 has four octaves of miniature keys, plus performance controls positioned for 'round-the-neck' playing. It's an obvious rival to the successful Casio CZ-101, and since it sells for around the same price it will give many purchasers a difficult decision between the prestige of FM and the flexibility of Casio's Phase Distortion sounds.

HOW THEY DIFFER

The DX100 and DX27 voicings are to all intents and purposes identical. While the DX21 had eight voices splittable at any point on the keyboard, the 27 and 100 each have eight voices with no split option. While the DX-21 had 128 preset sounds, the DX27 and 100 each have 192. While the DX21 had 32 RAM memories, the DX27 and 100 each have only 24...

And so it goes on. It's easier to list the differences between the DX27 and DX100 than it is to list the many similarities. The smaller DX100 has a sprung up/down pitch bender and a modulation wheel on the rear edge, while the larger DX27 has wheels on the front panel a la Moog Rogue. The 100 can be battery powered or can use an optional mains transformer, whereas the 27 works only from the mains transformer supplied. And the 27 has a music stand while the DX100 does not. That's about it as far as the differences are concerned, so from this point on we'll refer to the DX100 which, as we'll see, may work out the better bargain.

The DX100 voice, like that of the discontinued DX9, is based on four FM operators. Anyone who has been living in a cave for the past few years may find the following pocket definition of FM synthesis handy: Analogue (subtractive) synthesis takes complex waveforms and cuts them down using selective filtering. Frequency Modulation (FM, digital, or additive) synthesis takes simple sine waves and stacks them up to create something much more complex than analogue synthesis could create in a month of Sundays. Now the industry standard Yamaha DX7 has six operators (FM sine wave generators) in each voice, but that doesn't mean that the DX100, limited to four operators, doesn't get a look in. Even a single pair of operators (one operator by itself gives only a boring sine wave) can create very complex sounds, so four operators give plenty of possibilities. The DX100 will give you brass sounds, piano sounds, breaking glass sounds, wind, bells, windbells, lots of things, all with a power and realism belying its compact size.

The basic form of each sound is decided, as usual, by the algorithm used. This is the order in which the operators modulate each other's frequency, and decide whether the sound has one main audio component and three kinds of modulation, two of each, or three audio components and only one kind of modulation (of course, there are envelopes and other functions to be taken into account as well). The DX100 has eight alternative algorithms.

The machine also has an impressive stack of factory programmed sounds-192 in all. These are accessed through a mode known as Bank Play, and the sounds are arranged in four banks of 24 (Shift Mode gets at the second group of 96 presets). The preset sounds are as follows:

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | |||

| Pianos | Basses | Comping | Perc II |

| E-pianos | Brass | Lead I | Effects I |

| Organ | Strings | Lead II | " |

| Plucked | Keybds | Perc I | Effects II |

| Shift | |||

| Pianos | Organ | String | Perc I |

| E-pianos | Plucked | Keybds | Perc II |

| E-pianos | Brass | " | " |

| Organ | String | Leads | Effects |

In other words, an excellent selection of sounds once you've learned how to get at them. Some of the Effects such as 'Space Talk', 'Smash' and 'Windbells' are tremendously impressive, and there are a few utilities such as FM Square, FM Pulse, FM Sawtooth, LFO Noise and Pink Noise which could well come in useful.

The DX100 has just 24 programmable memories, and you can call up a bank of presets to fill them, or load any preset into any programmable memory for modification. There's a Preset Search mode which makes it easier to skip along the preset banks, and all sounds and banks are selected using squashy rubber buttons which you'll either love or hate. Presumably they're cheap to fit...

Sound creation follows the usual Yamaha FM path of choosing an algorithm, selecting the basic audio frequencies of the carriers (those operators which actually produce audible pitches), choosing frequency ratios for the modulators (the operators which act on the carriers to give them a more complex tone) and defining multi-stage envelopes for all the operators. Although this sound creation system is still more complex than on any analogue synth, it is slightly more logical than on the DX7. For instance, if you choose a parameter in the Function Mode you can alter its value by repeatedly pushing the parameter button rather than by having to refer to the Data Entry slider or +/- buttons.

The LCD window also tells you what's going on more comprehensively than in the past (incidentally, on the DX100, but not on the DX27, there's an LCD Contrast control to compensate for odd viewing angles). You'll be told whether you're in Preset or Internal memory mode, Function mode and so on.

There are some complexities though - remembering that you have to press Shift and -1 to get out of Shift Mode, and learning the difference between Internal, Bank and Preset memories for instance.

As we've mentioned, the DX100 has 24 Internal memories and 192 Preset memories. The Bank memory consists of 4x24 spaces which allow you to arrange groups of sounds for specific purposes - for a particular live set or studio session, for instance. The Edit Bank function allows you to load sounds from Internal or Preset memories into Bank memories, and while the function is useful - who wants to go searching through 192 presets for the sound you want in the middle of a live set? - some would gladly swap it for a second bank of 24 programmable internal memories.

Unlike the DX7, the DX100 dumps sounds to tape which, while memory cartridges are still around £70 each, will remain economical if slow. However, it has one major advantage over the DX7, the provision of Performance Memories. In an ideal world, all synthesizers would store individual pitch bend, portamento, modulation and other values for each patch, but memory costs money and most manufacturers assume you'll have a favourite pitch bend depth - perhaps a fifth - and a penchant for a certain kind of vibrato modulation.

So the DX100 does score in this area. As long as you remember to store the values, you can have (for instance) a sound programmed to Mono Mode, with New Note Priority Glide and After Pressure Vibrato at a suitable depth - the Mono Bass patch being an excellent example. You can set any of three pitch bend modes - Low, High and Key On. Low and High modes will only bend the top or bottom notes held while the others stay put, which makes for some interesting effects, while Key On simply bends the lot as per the DX7.

There are two Portamento modes, two programmable Footswitch modes (for Portamento or Sustain control), various options for the old spit-down-the-sweater generator (Yamaha still persist in referring to it as the BC-1 Breath Controller), flexible Voice Naming, and Key Transpose.

MIDI FUNCTIONS

That's about it for the programmable performance parameters. The DX100 also features all the bread-and-butter functions for dumping and recalling sounds and for controlling its MIDI functions, the latter of which deserve a closer look.

The DX100 is very much a product of the MIDI generation, and as we've implied, could well find its major application as a MIDI expander. It's infinitely easier to use than a TX7 (which is only truly compatible with a DX7 anyway), it has its own keyboard without being too bulky, and it's VELOCITY AND PRESSURE SENSITIVE OVER MIDI. Bet that woke you up. The ability to create velocity effects from a DX7 or other velocity-sensitive synth or mother keyboard, or from a velocity-programmed sequencer such as the QX1, QX7 or Roland MSQ-700, takes the DX100 into a whole new world of sound.

Quite apart from velocity and pressure response, the DX100 can deal with Sustain, Mono/Poly, Pitch Bend, Modulation, Breath Control, Data Entry, Volume, Portamento and Patch Change information over MIDI, or completely sever itself from any outside MIDI influence using the MIDI On/Off function. It can dump sounds via MIDI to another DX100 or DX27, or deal with 24 of the sounds from a DX21, the remaining six having to be loaded one at a time using the cunningly named Load Single function.

The almost-60 page handbook for the DX100 is, to say the least, comprehensive. If you want to rewrite the machine's operating ROM, here's the book to help you do it (we exaggerate slightly). But a few interesting facts do turn up - such as the ten-hour battery life, which seems reasonable, the MIDI Active Sensing (which means that notes won't drone on if the MIDI In lead is accidentally pulled out), and the table of frequency ratios for the operators. While the DX7 allowed you to use any ratio at all, the newer designs offer a large selection of the more obvious ratios (64 of them for each operator) which will help you create sounds more quickly. Probably only the computer musicians at IRCAM Paris will feel a sense of loss.

Both the DX100 and the DX27 have headphone sockets and MIDI Thru sockets, and on power up flash a hearty "Welcome to DX!" message on the LCD display. Heartless cynics amongst you will be glad to know that this message can be changed to anything you like.

CONCLUSIONS

Now comes the time to make some recommendations about the DX100 and DX27, which will of course be slightly modified by your personal needs. There are very few negative points to be made - of course, it's awkward learning the difference between Bank, Internal and Preset memories, how to copy operator envelopes or change the frequency ratio of the third carrier along. But that's all part of FM, and the new DXs certainly deliver the goods in performance once they're programmed up to your individual needs.

But the DX27 fails to move me. It's perfectly adequate as a budget keyboard, perhaps for the beginner intending to move up or for the analogue synth devotee who wants to add FM sounds relatively cheaply. But the machine just seems like a DX21 without the key split and with even fewer programmable memories - it's £200 cheaper (£499), but if it's cheapness we're looking for, at £349 the DX100 is definitely the one to go for.

As a MIDI expander, the DX100 is incredible. Lots of scratch preset sounds, enough memories to store your favourite patches, enormously compact but with a keyboard large enough to play if your mother keyboard isn't to hand. Amazing MIDI response, battery power for portability with performance controls for on-stage posing if that's your thing. It's a bit too big to go into a 19-inch rack, but should find a place in every home studio - and in a lot of professional outfits too.

(Contact Details)

Also featuring gear in this article

Yamaha DX100 - SynthCheck

(IM Feb 86)

Yamaha DX100

(12T Mar 86)

Patchwork

(EMM Apr 86)

Patchwork

(EMM Oct 86)

Patchwork

(MT Mar 87)

Patchwork

(MT Feb 88)

Patchwork

(MT Oct 88)

Patchwork

(MT Mar 89)

...and 5 more Patchwork articles... (Show these)

Browse category: Synthesizer > Yamaha

Featuring related gear

FM 4-Operator Editors

(MT Jul 88)

Quinsoft 4-OP Librarian - Atari ST Software

(MT Mar 90)

Browse category: Software: Editor/Librarian > Dr. T

Browse category: Software: Editor/Librarian > Quinsoft

Browse category: Software: Editor/Librarian > Soundbits

Publisher: Sound On Sound - SOS Publications Ltd.

The contents of this magazine are re-published here with the kind permission of SOS Publications Ltd.

The current copyright owner/s of this content may differ from the originally published copyright notice.

More details on copyright ownership...

Review by Mark Jenkins

Previous article in this issue:

Next article in this issue:

Help Support The Things You Love

mu:zines is the result of thousands of hours of effort, and will require many thousands more going forward to reach our goals of getting all this content online.

If you value this resource, you can support this project - it really helps!

Donations for October 2025

Issues donated this month: 0

New issues that have been donated or scanned for us this month.

Funds donated this month: £0.00

All donations and support are gratefully appreciated - thank you.

Magazines Needed - Can You Help?

Do you have any of these magazine issues?

If so, and you can donate, lend or scan them to help complete our archive, please get in touch via the Contribute page - thanks!