Magazine Archive

Home -> Magazines -> Issues -> Articles in this issue -> View

Zoo 2000 | |

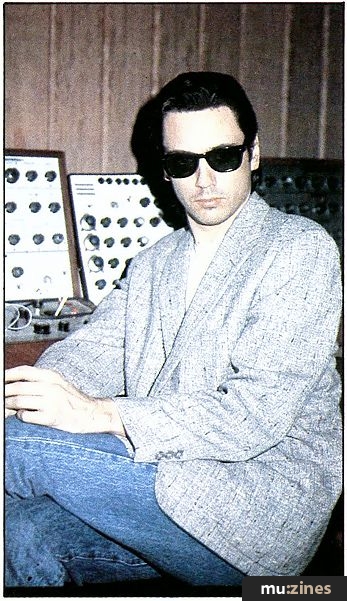

Jean-Michel JarreArticle from Electronics & Music Maker, February 1985 | |

Take one of the most influential electronic composers of the current generation, a Fairlight, an entire library of vocal recordings from all over the world, and a few more-than-talented guest musicians, and you have the recipe for Zoolook, Jean-Michel Jarre's latest album. Here he talks about its creation.

France's most successful composer of electronic music had a new album, Zoolook, released at the end of last year. Here he explains the motivation behind the recording and describes the technology that made it possible.

Whenever one of electronic music's most influential figures foists a new long-playing record on the unsuspecting public, that public tends to sit up and take notice. Even more so if it's been the best part of four years since he released a collection of all-new work, and if he's recruited a number of other well-known musical experimenters to assist him in the new album's production.

The figure in question here is Jean-Michel Jarre, the album is Zoolook, released in the UK by Polydor at the end of '84, and among the collaborating experimenters are Marcus Miller, Adrian Belew and Laurie Anderson. In fact, none of those three characters made an especially large contribution to the new record. Zoolook is first and foremost Jarre's work, from conception to execution, with the other artists drafted in to spice things up a little as and when the composer saw fit.

It's a remarkable album in many ways. More than any other Jarre recording, it relies heavily on the talents of computer technology (in the shape of the Fairlight CMI and the Emulator), partly because the machines have improved immeasurably since the recording of Magnetic Fields, the composer's previous all-new release, but mostly because a major element within Zoolook's sonic make-up is the sampling - and subsequent electronic treatment - of vocal snippets from a huge variety of cultures and ethnological backgrounds.

Language Samples

What inspired Jarre to attempt such a task?

'Well, it was a concept I'd been thinking about for quite a long time. Five or six years ago, the Director of the French Opera asked me to consider writing a modern opera, though not necessarily a rock opera. I was interested, but also a bit cautious about accepting the offer, because I consider that the operatic form is better suited to the 19th century that it is to the 20th: the most famous opera composers of today are in fact people like George Lucas, Stephen Spielberg and Stanley Kubrick - film directors rather than musicians.

'On the other hand, I was also interested in refashioning some kind of operatic form, treating the vocals in a manner entirely different to what rock music tends to do with them. When the China concerts ended, so did a certain period of my career: I had become tired of the more usual sorts of synthesiser music, and particularly the cosmic Star Wars approach adopted by so many people today. So I became continually involved in the everyday sounds around me - instruments like the Fairlight allow you to do that nowadays.

'I did a lot of travelling at that time, and it occurred to me that the way many musicians use pure ethnic music seemed rather artificial. It's become fashionable over the last three years or so to take a group of ethnic instruments and juxtapose them with rock ones, but that seems incongruous to me. Sometimes it can work - as it does with Peter Gabriel's music - but that sort of thing I consider to be the exception. It seems to me much more interesting to take words or parts of words from different languages and work with them.

'Some of the voices and words on Zoolook were recorded during my travels, while the others are the result of my working with a French ethnologist, Xavier Bellanger, who had travelled a great deal himself and had a large collection of tapes. We listened to all the sounds between us and I selected the words I wanted to use. My selections were based on phonetic or musical qualities rather than what the words meant as such.'

It's the sheer scope of the linguistic samples present on Zoolook that gives probably the best clue as to why the album took so long coming. Languages used include such oddities as Aboriginal, Balinese, Eskimo, Pigmy and Sioux, but not all the album's samples are voices, and not all the instruments used are samplers. Because Jarre still finds time for lower-tech hardware in the form of ancient Moog, ARP and EMS synthesisers, his custom-built Matrisequencer, and a Mk1 Linn drum machine as well as a more up-to-date model. The assortment makes for a colourful collection full of interest and vitality, and that's precisely the composer's intention.

Synthesisers

'I like to be adaptable where synthesisers themselves are concerned', Jarre affirms. 'I wouldn't like to limit myself to any particular system, be it analogue or digital - the reason I use any instrument is simply that it can make the sound I require. Because as you know, every synthesiser has its own specific sound.

'Generations of instruments come and go, and some of them will be good and others not so good. If you take the violin world as an example, it's probably the dream of the average violinist to play a Stradivarius, an instrument built in the 17th century. And that's because nobody since then has succeeded in building a violin with the same actual sound. It's my opinion that the same goes for electronic instruments: second or third generation instruments are not necessarily preferable to those from the first.

'For example, I consider some of the sounds on the first Linn are much better than those on the LinnDrum, but because the LinnDrum has greater programming possibilities and some of the sounds have been improved, people have a tendency to think that it is automatically a better instrument.

'And I don't think there's any way that the newer Japanese instruments such as the DX7 will ever replace the older analogue synths. It takes a long time to edit sounds on them because altering parameters is so complicated, and in almost every respect they represent a completely different approach. If anything, the Japanese seem to be considering synthesisers as versatile organs - they're thinking primarily in financial rather than musical terms.

'That's why I prefer to weigh up the possibilities of any new instrument very carefully. And strangely, the last patch I constructed was an old Moog 55 - a modified one that used to belong to Robert Moog himself.'

And in addition to the composer's sampling computers and purely electronic sound generators, Zoolook also has its fair share of conventional rock instruments, courtesy of the collaborators mentioned above. As a result, some of it sounds decidedly commercial and accessible by comparison with some of Jarre's previous works, though it's unlikely Tommy Vance will ever play it on his Radio 1 rock show. Because although the instruments themselves might be conventional, the musicians playing them do so in decidedly off-the-wall ways, which is what attracted Jarre to the idea of working with them in the first place.

Collaborators

'It was a combination of factors that made me decide to use other artists on this album. I chose the people I did because I admired their previous work and because I felt they could lend something useful to the album as a whole, but there was also the fact that working with synthesisers can be very lonely. You have to approach it like a painter, alone in a bunker or something, so the idea of integrating other people came quite naturally.

'I tried to choose artists that were known not only for their session playing ability but also for working at the very edge of their particular field. For example, I consider Marcus Miller to be not only the best bass player in the United States, but also someone who has a very unusual approach to his instrument: he's able to play rock, jazz, breakdance, any number of styles. And Adrian Belew is someone who probably forgot what a typical guitar sounded like some time ago. He's able to get just about any sound out of his guitar, and was therefore fantastic to work with. Then there's the dummer, Yogi Horton, who's also a very flexible musician: he's worked with Talking Heads and on many different kinds of sessions.

'As for Laurie Anderson, she's so much more than a musician: she's really a multi-media artist. I've admired her work for quite a long time from a graphic and conceptual point of view, as well as from a musical standpoint. I enjoyed working with her enormously - she was always subtle and delicate, and the way she talks, moves and performs reminds me continually of a Japanese opera singer! She'd brought back some recordings of Japanese words after her tour there, and we mixed them into other sounds.

'I also asked her to sing something as if it had been written by aliens from another planet - the idea was that she wouldn't be able to understand the meaning of what she was singing, only the emotions behind it. She did it all beautifully.'

It can't have been an easy task, capturing all that artistic and technological energy on tape, yet already, Zoolook has been on the receiving end of a good deal of laudatory comment from the recording cognoscenti. Obviously, much of the credit for that must go to Jarre's own technical and musical expertise, but the composer himself has much praise for mixing engineer David Lord, whose own experience of producing computer instruments in tandem with acoustic ones proved invaluable.

'Only the title-track from Zoolook was not mixed by David Lord', he recalls. 'He knew just how to cope with Fairlight sounds because he co-produced Peter Gabriel's last album, and he also used to be a classical conductor and keyboard player in his own right. I liked his sensitivity and versatility very much. He was actually quite impressed by the Fairlight sounds I'd created and used on the album. I took a long time constructing them with a lot of high frequencies and harmonics, because as you know, wide bandwidths are difficult to achieve on the CMI. I also had to use a lot of tricks such as compressing and expanding the sound: there's actually the same amount of treble on the Fairlight voices as there is on Laurie's vocals, and as you can imagine, that took a long time to perfect.'

But the temptation to use other instruments - such as the Synclavier and Emulator II - with wider frequency response hasn't yet been yielded to?

'Well, the new Emulator was released after the record had been completed, so it was, ahem, rather difficult to make use of it. But seriously, the trouble with modern technology is that it's not always worth learning how to use yet another new instrument, especially when you consider that it might take just as long as it would to learn the guitar, piano or flute. Just because you can play one synthesiser, doesn't mean to say you can play them all. And at the moment, I like the Synclavier but can cope much better with the Fairlight, so I'm happy with that.'

"I feel that the fewer statements are made about music, and the more music is listened to, the better."

History

E&MM took a long and detailed look at Jean-Michel Jarre's musical past when we last interviewed him, back in June 1982. There seems little point repeating it all here, but one historical fact to which many commentators have attached great importance is the fact that Jean-Michel is the son of two highly musical parents. Even before he'd made his first commercial recording, his father was a notable filmscore and soundtrack composer. Did that fact really have a far-reaching effect on Jarre's career?

'Ironically, my parents separated when I was only five, and I grew up without my father as he was living in Los Angeles: I didn't see him at all between the ages of five and fourteen, and after that only once every couple of years. So I think any influence must be hereditary, and I don't think my father's being a musician has been an advantage or a disadvantage, really.

'But one man who did play a large part in influencing me was Pierre Schaeffer of the Music Research Centre in Paris (which Jarre attended in 1968 after graduating in harmony, counterpoint and fugue at the Paris Conservatoire). He was the first man I met who was able to think not just in terms of harmonies and rhythms, but also in terms of sound textures.

'On the whole, though, I found the whole attitude of people at the Research Centre too intellectual to be really interesting. I believe that there is some sort of quality in every type of music, but although intellectual approaches are very interesting on a purely intellectual level, I'm not so sure they're very useful from a musical point of view. In fact, I think an excess of intellectuality can actually be very dangerous. It can lead people to believe that cultural and intellectual background is what makes music more or less interesting. That tends to be the attitude of contemporary classical enthusiasts, who favour the likes of Boulez and Xenakis.

'I think it's totally absurd to have to write a book to explain a certain concept, then another to explain why that concept was a failure. Personally, I prefer to think of music in terms of whether or not it gives me the shivers! The worst crime of all nowadays is to justify the music you're writing in terms of the instruments or musical concepts you have in mind. Recently, I have come to feel more and more that the fewer statements that are made about music and the more music is listened to, the better. The end result should speak for itself. Mind you, there's nobody worse than the French for analysing and explaining.'

And, as if in acknowledgement of the truth of that last statement, Jarre continues at some length on the reasoning behind Zoolook's highly individual arrangement and why its release - or the creation of something like it - has been on the cards for some time.

'After I left the Research Centre, I secured a contract with the Paris Opera, so I was quite involved with contemporary classical music as well as the rock world. I didn't want my music to be a compromise between the two, rather a means of integrating them. That's why I spent time doing so many different things, TV commercials, soundtracks, ballet music, producing rock singers, writing lyrics and generally experimenting - in unconscious preparation for some future project that would involve music without any specific lyrics.

'I'm convinced that today's public is conditioned to listen only to songs. In their eyes, instrumental music represents only commercials and soundtracks, which to me seems crazy. Zoolook is vocal rather than instrumental music, but it has no lyrics as such, and why should it? What difference does it make whether or not you add lyrics to a song? On Zoolook, the voices are used as other instruments, so that even some of the rhythm tracks are made up of sampled words, treated and arranged to take the place of percussion.'

Museum Pieces

Setting aside for the moment the subject of Zoolook (because for all the originality and elegance of its musical motivation, it sounds at times uncomfortably like a very comprehensive Fairlight demonstration record, or the sort of thing E&MM's Paul White would come up with given a drum machine, a Powertran MCS1 and unlimited 48-track studio time), the record is not in fact Jarre's first original vinyl offering for four years, as we might have implied earlier. Because in addition to there being a number of previously unreleased pieces on the live Concerts In China double album, the composer also made a totally new LP a year or so ago. And if you're wondering why it never appeared on the shelves of your friendly local High Street record shop, the reason is that only one copy of the disc was ever pressed. Given that Jarre must be as aware as any other artist that commercial reality and record company practice demand that he should try to sell as many records as possible, what prompted such a surprising and flagrant piece of anti-marketing.

'It started as a result of a request from a group of friends of mine who are painters and sculptors. They were planning to stage an exhibition at a Paris gallery that would include, for example, normal supermarket products transformed into art. They asked me to provide the music, which I did. So the record became a single work of art, like a painting.

'I like the idea of a record as a single object, which is an attitude that harks back in a sense to the sixties and seventies, when everything about a record was regarded as having an almost magical quality, even down to the way the sleeve was printed. It's still the same with books: the cover, and the smell and feel of the pages all count towards a book's overall quality. Yet nowadays, I think records tend to be regarded as if they were no more than Kleenex boxes.

'My album was a reaction against that, something that made the point that a record could be interesting as a single entity. In one sense, it was also a joke at the record company's expense, because it was the very opposite of their usual practice, which is to emphasise a record's commercial potential.

'That's why it was only played once on the radio - it became an open invitation to anybody wanting to make an illegal recording and then sell it. You can imagine the record company's reaction to that! It was quite fun, and it may also have made the industry realise that the reason record piracy is flourishing is that the public sees a record as a work of art, while the record companies see it as just another mass-produced commodity.'

And, like countless other composers who've stuck to their artistic guns and refused to give in to the dictates of commercialism, Jarre had great difficulty getting as far as being able to release his work to the public in the first place, as he recalls.

'Because Oxygene (Jarre's first successful recording) consisted of entirely instrumental music, none of the record companies thought it would work. The only people who took the 'risk' of releasing it were a small French company called Dreyfus Music. Even after it had become a hit in France, people said it couldn't possibly be a success anywhere else. Then eventually, after it got to the top of the charts in Britain and all over Europe, the critics explained that it was successful because of its originality and because of its use of melody. It's easy to be wise after the event.

'You know, there'll always be a continual fight between the artists and the music industry. In a way, I feel extremely privileged to be in a position where I'm able to write the music I want to. Every day I receive enthusiastic fan letters from England, France and elsewhere, in which people comment on the music in an intelligent fashion, and that seems to be symptomatic of a healthy relationship between artist and audience. To me, achieving contact with my audience is the most important aspect of my music.

'I don't really care whether there are only five people deciding what music is played on English radio, and that my album doesn't receive much airplay as a result, though obviously it's a very sad state of affairs. And I don't care if I don't receive any attention from the press or other media, because my records still seem to sell well without much in the way of airplay or press coverage.'

Visions of China

Jarre's dislike of the press in general, and the British press - E&MM excluded, naturally - in particular, stems from the sound battering the first of his China concerts received from almost all significant quarters. Was he affected by that criticism, and does he still look back on his Oriental trip as a satisfactory accomplishment?

'It was undoubtedly worthwhile, partly because of the fact that in China, you're free of all the Western media's attitudes to modern music. Even when I was there, they made a great fuss about my being the first person to play that sort of music in China, and set me up as some sort of Tintin figure, which was utterly ridiculous.

The reviewers knew we were bound to have problems with power and so on during that first concert, but they took no account of that, and treated it as if it were just another gig. In fact, all the other shows were perfect: it was only at the first concert that technical problems were encountered.

'In all, I was very impressed with the Chinese musicians' standard of playing, considering that, due to the lack of power, we'd had no rehearsals as such. The first time we played together was that first show, and everything went perfectly for them. Our playing was another matter, I think, but I still regard it as most successful, from a personal as well as a musical point of view.

More with this artist

The Concerts In China (Jean-Michel Jarre) |

The French Connection (Jean-Michel Jarre) |

The French Connection (Jean-Michel Jarre) |

Docklands Rendezvous (Jean-Michel Jarre) |

Sound And Vision (Jean-Michel Jarre) |

Publisher: Electronics & Music Maker - Music Maker Publications (UK), Future Publishing.

The current copyright owner/s of this content may differ from the originally published copyright notice.

More details on copyright ownership...

Interview by Paul Wiffen, Dan Goldstein

Previous article in this issue:

Next article in this issue:

Help Support The Things You Love

mu:zines is the result of thousands of hours of effort, and will require many thousands more going forward to reach our goals of getting all this content online.

If you value this resource, you can support this project - it really helps!

Donations for November 2025

Issues donated this month: 0

New issues that have been donated or scanned for us this month.

Funds donated this month: £0.00

All donations and support are gratefully appreciated - thank you.

Magazines Needed - Can You Help?

Do you have any of these magazine issues?

If so, and you can donate, lend or scan them to help complete our archive, please get in touch via the Contribute page - thanks!