Magazine Archive

Home -> Magazines -> Issues -> Articles in this issue -> View

Take Two | |

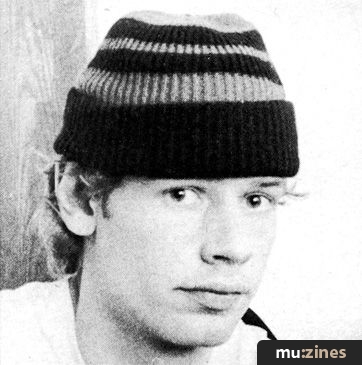

Moraz and Bruford Embrace the New | Patrick Moraz, Bill BrufordArticle from Electronics & Music Maker, July 1985 | |

Patrick Moraz and Bill Bruford, two of music’s best-established virtuoso players, talk about their two-year relationship and a new LP. Interview by Dan Goldstein.

They started their career together as a piano and drums group, but now, two of modern music's most distinctive instrumentalists have added high technology to their line-up.

It's a hot, sticky Sunday afternoon in Central London, and two musicians, both as experienced in and as dexterous at their craft as any you could wish to meet, are in the throes of a last-ditch attempt to salvage some semblance of a live set from a recorded repertoire that's been almost entirely improvisational. The scene is Good Earth Studios, a sprawling underground recording complex with an over-enthusiastic air-conditioning system that succeeds in making the interior as chilly as the exterior is humid. Even so, the players in question, drummer Bill Bruford and keyboardist Patrick Moraz, are sweating from their endeavours, and are initially reluctant to take a break from them.

'It'll have to be quick', mutters Bruford as he enters a rest room for some coffee. 'We've got a gig to do on Tuesday and it isn't really happening.' But it isn't quick. Both artists have got a lot worth saying, and given a little journalistic prompting, are more than happy to dedicate some of it to tape.

Bruford is taller, calmer and more confident than his new-found musical partner. His list of playing credits reads like a catalogue of English seventies progressive rock: spells with Yes, Genesis, National Health, UK, a short-lived eponymously-titled outfit, and most recently, the rejuvenated King Crimson. His speech is clear and economical, but blissfully free of crass generalisation or unprovoked criticism of fellow musicians. And his prowess as a drummer, of course, is beyond question.

By contrast, Moraz is nervous, jittery and difficult to pin down. Like many great musicians, he's so addicted to what he does that any interruption to his train of composing thought is greeted with a shrug of the shoulders and an expression that says 'Can't you see I'm playing here?'. Eventually, though, the Swiss-born multi-keyboardist warms to the prospect of a musician's conversation. Thoughts of his equally impeccable pedigree (Yes, The Moody Blues, and a broader range of solo projects than most composers are capable of undertaking in a lifetime, let alone the decade or so they've taken Moraz) are soon swept to one side as he gets stuck into the real business of talking about what modern music is, how it's made and why people make it.

Background

The coupling is an odd one, certainly, but it's been in existence for a couple of years now. It's resulted in two LPs, the critically-acclaimed Music for Piano and Drums, and a new, more instrumentally-varied release called simply Flags. And now, the duo are embarking on a fairly lengthy (and geographically diverse) concert tour that's to serve more than just a promotional function; above all, Moraz and Bruford just want to play live, in front of an audience.

But more of that later. The first, most obvious question that must be asked of any couple is 'why get together in the first place?'

Bruford has the reasons at his fingertips. 'The first is economics, the fact that it's a lot cheaper to record, rehearse and gig with two than it is with five or six. Musically, I think two is a good number because it means nobody's fighting for anybody else's aural space. In King Crimson - and Patrick would probably say the same for The Moody Blues - you know you can't play as much as you want to because you'll end up clashing with what other people are doing, especially now that technology has given each musician such a wide range of available sound-generation. It's quite a strong discipline holding back like that, and with just the two of you playing, you know that no matter what you do, you won't be heading for a complete aural mess.

'Then there's the question of logistics. If you've ever been in a group, you'll know that the more people there are involved in it, the more difficult it is to organise. So that was an advantage, coupled with the fact that Patrick and I live about 400 yards from each other, which is also a great help, obviously.'

But what about music? Surely there must have been some common musical ground between the duo that made them want to play, compose and record together?

Bruford isn't sure. 'Um, I don't really know. Perhaps you'd better ask Patrick. Patrick, have we got anything in common, musically?' Moraz pauses for quite a while. Then: 'No. No, not really.' Now there's a strange feeling of unease in the room, as if a couple about to be married had suddenly realised they didn't like each other very much. Bruford continues the analogy in his own speech.

'I suppose it's a marriage of opposites. We're quite different from each other in many ways. We have very different personalities both inside and outside music. So to an extent, I think we agree to disagree.

'There's a reason for that. It's important, I think, to have some degree of tension in a group, though it's equally important that you don't let that tension get out of hand. But if you have a group in which everybody agrees with each other most of the time, that can result in some very bland, predictable music. And if there's one thing that Patrick and I very much wanted to avoid when we started playing together, it was bland, predictable music.'

Improvisation

The route Moraz and Bruford have taken in their quest to avoid blandness and predictability is a well-trodden one: that of improvisation. As the supplier of melody, it falls to Moraz to do much of any initial writing the duo might feel is necessary, while Bruford feeds off him to derive a suitable percussion part, often giving the keyboardist some inspiration in return. It's a familiar enough pattern, but to find it used with such dedication and perception is rare - especially in the rock field.

In a fit of musicianly modesty, each player is anxious to apportion credit to the other. Bruford: 'Patrick is a very talented player, very quick, and very adaptable. He's an excellent writer, but the speed is the main thing. When we got together, one thing we desperately wanted to get away from was the endless rehearsing and six months to make an album that are the norm in a larger group format. So, that's been a major priority, to keep things as spontaneous and as rapid as possible.'

Moraz agrees. 'Although Bill and I have different personalities and different musical tastes, we do have similar thoughts on writing and decision-making, so we work well together.

'We want to make things happen as quickly as possible, and in some ways we have to, because we both have so many other musical commitments to fulfil outside this group. At the moment I'm recording a new album here with The Moody Blues, and rehearsing with Bill in my days off. Then there's a 15-minute modular symphony I have to write within the next two weeks - and I haven't even started it yet. So time is of the essence.

"Just because you have a Kurzweil in the middle of the room, doesn't mean the 200-year-old Steinway in the corner doesn't have something to offer."

'But being highly-polished musicians, working with a lot of high technology, means that we're in the fortunate position of being able to experiment first and worry about the results later. We can take liberties with the mechanics of making music, even though what comes out at the end isn't entirely satisfactory...'

'...I think that's what'll probably happen at some of our first live performances', interjects Bruford, clearly relishing the prospect. 'We're bound to make a lot of mistakes at first, and it's quite conceivable that Patrick will select the wrong sound on the synth and end up playing a strings part on a piano. But that's what improvisation is all about. Nine times out of ten those mistakes don't really work and don't sound like anything more than mistakes, but on other occasions they do, and they show you an alternative way of playing something, a better way.

'That's one reason why I'm looking forward to playing live, because it introduces an element of risk that's even bigger than the one we're used to coping with in the studio. But then, I'm one of those eternal enthusiasts that's excited to play live period, no matter what attitudes I'm having to adopt. I expect the gigs to be fairly chaotic, maybe even rather wild, but the spirit will be there, and in any case, I rather like the chaos. It's not all that rare for chaos to turn into art overnight, and vice versa, of course.'

Instrumentation

If there's a recurring theme that runs through this duo's attitude to music-making, it's that self-limitation can be, paradoxically, the most broadening and eye-opening element. Their deliberate lack of rehearsal and pre-planning is one example of that ploy, and their choice of instrumentation is another.

As its title would imply, Music for Piano and Drums saw Moraz ditch his banks of synthesisers in favour of a traditional grand piano, and Bruford let electronics take a back seat to the open warmth and resonance of an acoustic drum kit. The technology was available to them, but they deliberately chose to avoid using it.

'It was by no means a facile or stupid idea', says Bruford. 'I think it's extremely good for musicians to realise - now and again - that just because you have, say, a Kurzweil in the middle of the room, doesn't mean to say Mr Steinway's 200-year-old creation in the corner doesn't still have something to offer. The older instruments are very, very beautiful, and it can be helpful to appreciate that once in a while.

'What we're trying to do now with Flags is draw attention to the contrast that exists between those traditional instruments and the very latest that technology has to offer. Patrick is using just a grand piano and a Kurzweil 250, and I'm using a combination of acoustic drums and the Simmons SDS7. Both the Kurzweil and the Simmons represent the top level of today's technology, but we're missing out all that went on between the two landmarks, and that's the interesting thing.

'It's an important and quite deliberate limitation. With Piano and Drums it felt as if we were painting with just red and blue, no other colours. This time around we've added perhaps green and yellow, so we've broadened things slightly, but the limitation is still there.'

'In many ways, I think you actually have more freedom when you're playing just the one instrument', Moraz continues. 'I've got all sorts of other keyboards, from Mellotrons to the Yamaha GS1, but I feel I've got more opportunities when I've got just the piano or just the Kurzweil in front of me. If you've only got one instrument, there's nowhere else for you to run. You've got to solve the problem there and then. That's the sort of thing that makes you a better musician, I believe.'

Technology

Speaking of limitations leads us back to technological specifics. Since both men have embraced new musical technology with a great deal of enthusiasm, it seemed worth asking them if they felt there was anything left for modern musical technology to achieve. Is there a particular task that Moraz and Bruford would like to see tomorrow's musical instruments performing?

'Not really', Moraz muses. 'What's happening now is that technology is slowly breaking down the barriers between people and making music. Just working with Passports Polywriter software, for instance, makes me realise that before very long, the skill of being able to write music in manuscript form will become largely redundant. Reading music will still be important, of course, but it's one less discipline that people are no longer forced to acquire.

The one really important thing technology can't do at the moment is participate in the writing process. But even that doesn't seem to be very far away. Something like the Kurzweil, for instance, is so intellectually powerful that it could easily be adapted to actually write music for you. I'm not suggesting that it would be nice to get rid of composers altogether, but to have the combination of human and computerised composition would be interesting, I think.'

Not surprisingly, Bruford isn't quite so full of praise for what contemporary percussion technology has to offer, but he's no less confident that progress will continue to be made - and fast.

'I'd say the sounds are probably all there now - these days I can even play pitched sounds on the drums while Patrick plays percussion sounds on the Kurzweil - so all that remains is the feel of the pads, that sort of thing. Drummers still aren't nearly as well catered-for as keyboard players in that respect, so there's still a lot of room for improvement when it comes to actually hitting an electronic drum and getting the feel and response of an acoustic one. But I do think progress is being made, and it won't be too long before things are more or less perfect.'

"We're in the fortunate position of being able to experiment with music first, and worry about the results later."

'Patrick is at an advantage because as a keyboard player, he's automatically given access to whatever technological developments occur. That's just traditional - scientists and researchers use keyboards as controllers because they're the most versatile instruments designed - but drummers aren't that far behind. Things are moving quite fast now, and certainly, something like the SDS7 is a big step forward.

Criticism

Behind all this technology, of course, lies a desire to increase musical proficiency and dexterity that is clearly still present in the minds of both players, despite the enormity of their past achievements and the performing skill they exude in such vast quantities. Refreshingly, they seem to possess humility in abundance, and are constantly striving to improve their standing as musicians.

'Being your own critic is one of the most difficult things to sustain', says Bruford. 'But it can also be extremely rewarding. One of the most important things is not to get too carried away by adulation. Both of us have had plenty of that at some point during our careers, but we've also been around long enough to have had periods of great unpopularity as well, and that's not necessarily a bad thing. If you're criticised by somebody else, it makes you more inclined to start criticising yourself, makes it more likely that you'll start seeing your own faults. And as soon as you recognise your faults, you can go about correcting them.

'I suppose the best way to improve your abilities is simply to carry on playing, as often and in as many different sets of circumstances as you can. It's difficult to put a finger on, but just being involved, daily, in an environment of high musical endeavour with Patrick makes me realise very clearly where my shortcomings lie, and just how big they are.'

It's more or less at this point that Moraz and Bruford realise that time is catching up with them, and that if our conversation is to continue, it's going to have to be in the main studio area while the duo resume their rehearsing.

As they begin, it's clear that things aren't 'really happening' now either, and both players start exhibiting signs of strain. How long can they continue like this?

Bruford: 'Oh, as long as we want to. I think both of us feel we're still some way off achieving what we really set out to achieve when we first formed the group. And I think we're both prepared to wait for quite a while before it starts to really come together.

'It's ironic in a sense. The actual mechanics of our playing together take place very quickly, so that, for instance, we only took five days to record Flags. But at the same time, the process of actually achieving our goals is a very lengthy, drawn-out one. It'll probably take years, in fact, perhaps ten albums or more.'

Five minutes ago, author and photographer would have dreaded the thought of another ten Moraz and Bruford LPs being foisted on the general public. Suddenly, however, the music emanating from the speaker system at Good Earth Studios has taken a distinct turn for the better. Where just a few moments before it had been disjointed and embarrassingly 'untogether', it now acquired a natural, pleasing flow that let us forget our prejudices and sit back, relaxed, in appreciation of two highly-talented instrumentalists going flat-out.

Like most improvised music, this is essentially a conversation between the participants that can easily leave an audience unmoved. The more dexterous those participants are, the more intense their dialogue becomes. And the more that happens, the more incidental the audience seems to be.

But in spite of that, Moraz and Bruford believe quite strongly that they are there to entertain their audience, and that they stand a better-than-average chance of doing just that.

'I suppose we are playing for ourselves first and foremost, because we're trying to achieve an elusive, almost unreachable goal that's unique to us. But I think almost all musicians go through that. They spend time sorting the good points from what they do and discarding all the dead wood, and all the time they're doing that, they're getting closer to attaining their particular goal.

'So I think our music will undoubtedly appeal to a good many musicians who can put themselves in our shoes, if you know what I mean. And I don't see any reason why ordinary listeners - people who've never played a musical instrument in their lives - shouldn't find something in it, either. Obviously, we can't listen to what we do using precisely the same criteria a non-musician would, but we can get close to that.

'One thing we wouldn't want to do, though, is compromise our music simply to satisfy the needs of the mass market. I mean, if the record company rang us up and told us they wanted Flags to be the next thing for teenage girls to fall in love with, I don't think we'd bother to take them seriously.'

Fair enough. Moraz and Bruford have been around too long to have to put up with that sort of compromise again. They're fortunate to have stayed the (quickening) pace of contemporary music, and they're equally fortunate to have almost complete artistic freedom now that they're approaching musical maturity. You get the impression that if that freedom was ever taken away from them, they'd probably just shut up shop and call it a day.

More from these artists

Patrick Moraz (Patrick Moraz) |

Patrick Moraz (Patrick Moraz) |

Patrick Moraz (Patrick Moraz) |

Bruford In Crimson (Bill Bruford) |

Bill Bruford (Bill Bruford) |

Strike That Chord (Bill Bruford) |

More from related artists

UK - The Rhythm Section (UK) |

Atlantic Crossing (Yes) |

Chris Squire (Yes) |

Django Live (Django Bates) |

The Struggle For Freedom (David Torn) |

The Yes Generation (Yes) |

In Praise Of Music (David Torn) |

At Home in the Studio (Genesis) |

Publisher: Electronics & Music Maker - Music Maker Publications (UK), Future Publishing.

The current copyright owner/s of this content may differ from the originally published copyright notice.

More details on copyright ownership...

Artist:

Patrick Moraz

Role:

MusicianKeyboard PlayerComposer (Music)

Keyboard PlayerComposer (Music)

Composer (Music)

Related Artists:

Yes

Bill Bruford

Artist:

Bill Bruford

Role:

MusicianDrummer

Drummer

Related Artists:

Yes

Genesis

Django Bates

David Torn

King Crimson

Patrick Moraz

UK

Interview by Dan Goldstein

Help Support The Things You Love

mu:zines is the result of thousands of hours of effort, and will require many thousands more going forward to reach our goals of getting all this content online.

If you value this resource, you can support this project - it really helps!

Donations for April 2024

Issues donated this month: 0

New issues that have been donated or scanned for us this month.

Funds donated this month: £7.00

All donations and support are gratefully appreciated - thank you.

Magazines Needed - Can You Help?

Do you have any of these magazine issues?

If so, and you can donate, lend or scan them to help complete our archive, please get in touch via the Contribute page - thanks!