Magazine Archive

Home -> Magazines -> Issues -> Articles in this issue -> View

DAR Soundstation II | |

Digital Audio RecorderArticle from Sound On Sound, April 1990 | |

David Mellor explores the higher echelons of audio technology and finds a machine which is destined to become a classic of its time: Soundstation II from Digital Audio Research.

One of the factors that first attracted me to professional audio, in the last but one decade, was the way that equipment was designed for a purpose. Chunky, hard-wearing, and straight to the point. If it looked good too, that was a bonus. But the heart of the matter was that the equipment had to do a job successfully and reliably. In the designer Eighties we saw the emphasis moving away from functionality more towards the look of the equipment. Often there would be immense inner substance but the external appearance - grey on black lettering, myopic LCD displays, and confusing 'hi-tech' methods of operation - would hinder the job in hand. In the post-designer Nineties, perhaps we will see a return to solid operational values, and with visual design that really helps the user get on with high quality audio production.

As you can see from the photo, the DAR SoundStation II is a pretty good looking piece of equipment. But wait till you get your hands on it - SoundStation II operates like a dream, with everything in the right place and all the info you need on a large touch-sensitive screen. This is real professional equipment and it costs real professional money. But maybe some of the excellent ideas it contains will change equipment for the better in the next few years [and filter through to more affordable products - Ed.].

PRODUCTION CENTRE

Digital Audio Research (DAR) call the SoundStation II a 'Production Centre' in their product literature. So what exactly is a production centre and what can it do for you?

In this instance we are talking about a multitrack digital recorder, recording two, four, eight or 16 tracks (depending on the system size) directly onto hard disk. As well as being a recorder, SoundStation II is also an editor. That may not sound like such a big deal, but when you have an editing system as powerful as this and so simple, then you begin to realise just what you can achieve with hard disk recording that you cannot with analogue or digital tape. Let's have a quick look at the SoundStation II console right now, with a more detailed explanation of the functions later.

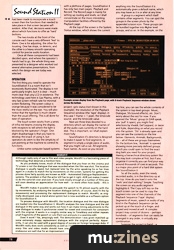

The console (there is also a separate processor rack) consists of a touch-sensitive screen, some 40-odd buttons, and a digital output level fader. At the front is the Vernier control (on the left), which is used to alter displayed values, and a Locator control, which is used to find the correct place in a cue. The touch screen (as shown in the screen photo) can list information about the project on which you are working, plus other material recorded onto the hard disk, including a directory of cue points to help the operator find the right bit of audio quickly.

Just below the screen centre is a display area which mimics magnetic tape spooling past a tape head. The 'tape head' is here called the Now Line. As the 'tape' passes through, all the named cues cross the Now Line and play as if they were real, physical, tape.

I'll come back to this feature in detail later on, but now is probably a good time to look at DAR itself as a company and find out why the SoundStation II came into existence.

"SoundStation II operates like a dream, with everything in the right place and all the info you need on a large touch-sensitive screen. This is real professional equipment..."

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

Digital Audio Research first made its mark when it was trying to promote the results of a lot of research into digital audio manipulation. The initial product was called Wordfit, a dialogue synchronisation system for the film industry, which was first promoted in 1984. At that time, it was one of very few hard disk-based recording and editing systems in existence.

Wordfit (described in a separate panel) was an expensive system selling into a fairly small market, but this didn't stop systems being sold to Burbank Studios and to Universal Studios in 1985, both of which are still in use today. It took another year to find the financial backing to develop a more broad-based product for the audio industry - SoundStation II.

The name SoundStation II implies that there must at some stage have been a SoundStation I, but in fact this is not the case. It is intended to signify that SoundStation II is a development of a previous product, which is of course Wordfit. SoundStation II was announced in 1987 and went into production in late 1988.

Given that it was to be a hard disk recorder and editor, the main design consideration was to protect the user from thinking that he was working with a computer. In other words, the aim was to make an editing system that is similar to working with tape. The user is presented with a model of tape editing and has a Locator wheel to simulate rocking tape reels by hand, and buttons which perform particular operations on the 'tape'.

Before settling on the touch screen as the main interface to the SoundStation II, DAR considered two alternatives: the traditional QWERTY keyboard, and the mouse (or its trackball near-equivalent). The disadvantages of keyboard input for speedy sound manipulation are obvious. The mouse has the disadvantage that you have to move the pointer from where it is to where it needs to be. With a touch screen, you just point. Once the decision had been made to incorporate a touch screen then the functions that needed to take place in that screen became self-evident. After that, decisions were made about which functions to offer as 'hard' buttons.

The two knobs at the front of the console each have a very different 'feel' to them. One is for adjusting, the other for locating. One has stops, or detents, and the other is a heavy smooth-operating control for precise audio location.

Once all these components had been decided upon, and where the operator's hands had to go, the whole thing was presented to a designer who worked out several alternative presentations, from which the design we see today was selected.

Example screen display from the Playback page, with 8-track Playback Sequence window shown across the bottom.

OPERATION

The first thing you need to operate the SoundStation II is a room that isn't excessively illuminated. The display is not particularly bright, but it is clear - much more clear than any LCD in existence. The technology used here is Gas Plasma, with a very fast screen refresh rate for minimal screen flickering. The screen colour is orange because it was considered to be the most restful on the eye. You will also notice that the typeface is much clearer than the usual offering. This is all done for ease of operation.

The touch screen works from a series of infra red beams crossing the display, with receptors to tell where the light is blocked by the operator's finger. One slight disadvantage is that you have to develop the knack of using it, but operators do seem to like the simplicity of just pointing at the machine to control its functions.

Unlike some computer-based systems with a plethora of pages, SoundStation II has only two main pages: Playback and Record. The Record page is mainly for setting up routing and levels, so I shall concentrate on the more interesting manipulation facilities offered by the Playback page.

At the top of the screen is the System Status window, which shows the current project; sync status (not shown in this example); the resolution of the Playback Sequence window (the 'tape' display), in this case 1 frame = 1 pixel; the time code source; and the timecode value.

Next are three lines devoted to a directory which can display the names of all the audio cues currently on the hard disk. This is important, so I shall explain more fully:

"...if this is the future of audio in the Nineties then I want more of it!"

SoundStation II's directory is designed to make it easier to find segments. A segment is simply a single piece of audio, that you might call a cue. All segments have names. As soon as you record anything into the SoundStation it is automatically given a default name, which you may leave as it is or alter at any time.

A group is a segment which itself contains other segments. You can spot the groups in the screen photo by the appended scissors icon. These groups can be bundled together into higher level groups, and so on. In the example, on the top line, you can see the whole contents of the system in top-level groups: Music, Dialogue, Sfx (sound effects), etc. Don't worry about the rest for now. If you opened the 'Music' group (in DAR-speak, you 'pull' it open), you might find selections by Vivaldi, Def Leppard, or Jason and Kylie, depending on what you record into the system. 'Sfx' is already open and you can see the contents on the line below: Elements, Animals, Backgrounds, etc - all of these are groups themselves. On the bottom line, 'Animals' is opened showing more precisely defined groups which you could open to find the exact dog bark you need for your project. Having a hierarchical directory system like this may look complex at first, but if you organise it correctly you can find your way around thousands of cues in seconds. This is a major plus point of a hard disk system like SoundStation II.

So all the audio, even the newly recorded audio, is in the directory up at the top. How do you load it onto the 'reels' and start editing? Simple. Touching the screen on any audio segment highlights it. The Copy soft key on the touch screen can be used to copy the segment into one of the channels of the Playback Sequence ('tape' display). Segments of music, speech or audio of any kind in the Playback Sequence can be picked up at the touch of a finger, and copied and moved at will. A complex project may consist of dozens - perhaps hundreds - of segments that can easily be arranged in any order, in virtually any combination.

Suppose the project in hand - a simple project - is to edit a recording of a song just to remove one verse somewhere in the middle. Let's say the segment is called 'Song'. Conventional transport controls are used to play the segment. If it is played up to the point where it is to be cut, you can stop the playback and move into 'Rock' mode. This is where we rock the reels of the imaginary tape recorder. In Rock mode, moving the locator wheel backwards and forwards moves the 'tape' under the Now Line - the imaginary playback head, remember? This is perhaps SoundStation II's best feature. The system is so solid, you feel as though there is a mechanical link between the Locator wheel and the 'tape' as you rock it backwards and forwards. It is actually more 'solid' than using a real analogue tape recorder, since there is no friction between the tape and the heads and no 'sag' in the tape tension arms. You may be aware that some other hard disk editors have an on-screen waveform display to assist in finding edit points. The audio reproduction in Rock mode is so smooth that SoundStation II doesn't need it.

When you have found the right point in the song, you can 'Cut In' with a hard button. If it's not quite right, you can 'Slip' this edit point forwards or backwards in time until it's spot on. There are, by the way, convenient auditioning facilities for listening to segments and newly cut segments. Also, by the way, you will find that your segment name 'Song' has changed to 'Song.1' before the cut and 'Song.2' afterwards - because now you have two segments. You can rename these if you like.

In a similar way, you can cut at the end of the unwanted verse so that you have three segments. Then, using the 'Bin' soft button, simply move the unwanted segment to the bin. The bin is where all your junk goes to and works like any other group. You can always retrieve material accidentally consigned to the bin, right up to the end of the session.

Hopefully the two segments you have left will join together smoothly. No? Well let's use the crossfade function. The beauty of hard disk editing is that it is non-destructive; the material recorded onto the disk is never changed. An edit is simply a software instruction to play the material in a different order with seamless joins. Crossfading between two segments can tidy up even the roughest of edits, as I shall demonstrate in a moment. But imagine that it is like running two stereo tapes in sync and pulling down the faders on one while pushing up the faders on the other. The length of the fade can be from zero up to more than you would ever need. Even when you have set a crossfade value, you can still slip the edit point. In fact, it is worth a try just to see if there is any improvement, remembering that you are not destroying anything.

The test I used on the SoundStation II's crossfade edit function, once I had tired of experimenting with all the 'easy' stuff, was to crossfade edit between two sections of a classical piece of music which were in a different key. This is, of course, impossible. But I tried it nevertheless. I made a rough edit, which sounded dreadful, and experimented with a few different crossfade times. A one second fade seemed smooth enough and matched the pace of the music. I experimented with the Slip function, and also with 'Trim' - which can lengthen or shorten either of the two sections being joined. It only took a couple of minutes to achieve a very plausible edit - you would think the orchestra had played it that way.

That other important editing function, gain matching, is also on-line. I don't think one could ask for a better editing machine.

When you have the perfect editor, you start to think what other tricks it could get up to. My next experiment was with a recording I had on multitrack tape. The song had three alternative vocal takes which I wanted to compile into one good take. Of course, this can be done manually, but it is difficult to get right.

I recorded the three takes directly into the SoundStation II, plus a guide track, syncing it to the timecode on the multitrack tape. The takes were anchored to the timecode so that the finished track would transfer directly back in sync. There are probably several ways of achieving this sort of editing with the SoundStation II, but it seemed best very roughly to cut up all the takes at the same time into individual lines while listening only to the first, then to name each segment with the first words of each line. Next, each was auditioned along with the guide track, assessed, and the two inferior takes consigned to the bin. After that, the good segments were trimmed to remove breaths and other unwanted noises, then the finished compilation was ready for transfer back to analogue tape.

Even at a first try, I could see that it's a lot easier to do this type of editing with the SoundStation than by any manual way. I even tried crossfading within a word, and the result was absolutely perfect.

DAR SoundStation II at Pelican Studio.

REAL WORLD APPLICATIONS

So much for my experiments - what is SoundStation II used for in the real world? Three examples are: Pelican Studio, who use it for post-production work, adding voice-overs, music, and effects to video; the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, who use it as a superior kind of multitrack and compile complete radio programmes on it; Autograph Sound Recording, who make sound effects for live theatre in their DAR-equipped studio.

The uses for SoundStation II as a music editor - including 12" mixes and the compilation of tracks for CDs - must be obvious. It only takes a moment's thought to see a multitude of uses for it as an aid to multitrack recording. Even a 2-track or 4-track SoundStation II system could greatly enhance the capabilities of any conventional analogue or digital multitrack recorder.

In short, if this is the future of audio in the Nineties then I want more of it! The DAR SoundStation II is a properly presented professional instrument. It is simple to use, has all the right features, it looks good, and it is damn good.

Thanks to Pelican Studio for an enjoyable session with SoundStation II.

FURTHER INFORMATION

On application.

Digital Audio Research Ltd, (Contact Details).

WRONG WAY TAPE?

This isn't of great importance to tape recorders, but when it came to designing SoundStation II's Playback Sequence display, which mimics tape, it was found that something had to be done.

Consider several pieces of tape, with the following phrases recorded on them:

"This is the first."

"This is the second "

"This is the third."

Now let's splice them together in the order they would be on real tape to play back in the right order:

"This is the third"

"This is the second"

"This is the first."

If these phrases were lines of a script, or words of a song, captioned onto the 'tape' of SoundStation II's Playback Sequence display, this would be really confusing. DAR thought long and hard about how far they should go to mimic real tape, and decided that their 'tape' would travel in the opposite direction. Thus the 'tape head' (the Now Line) scans, like our eyes, from left to right.

SOUNDSTATION EXTRAS

TimeWarp is used when your audio doesn't quite fit the correct time slot, like when a newly recorded 29 second commercial soundtrack actually turns out to be only 27.5 seconds long. TimeWarp can stretch or compress audio without changing the pitch.

TimeWarp is at its best in speech and sound effects. It is also useful for music, but although a good degree of success is likely, it isn't necessarily guaranteed.

Recording Crossfades

Crossfades, in hard disk audio systems, are performed by reading fwo sets of data simultaneously, from the audio section which is fading out and the section which is fading in. This would mean that an eight channel system would only be able to crossfade on four channels at the same time.

SoundStation II is able to record the data produced by the crossfade onto a new area of the hard disk. Once this is done it can be played back as if it were a new segment - although, in fact, apart from selecting the Record Crossfade function, it all happens transparently to the user. Crossfades are now possible on all tracks simultaneously.

WORDFIT

As you probably know, much of the dialogue that you hear on the cinema and TV screen is not the dialogue that was recorded when the film was shot. The location dialogue is usually taped, but replaced later by the actor speaking his or her lines again in a studio to match the lip movements on the screen. Systems for getting this process done fairly quickly are known as ADR - Automated Dialogue Replacement - systems. The problem is that the actor still has to get it right. ADR just makes it easier to do the same bit over and over. If you look closely enough at a number of films you will soon develop an appreciation for how well - or more often how badly - this is done.

Wordfit makes it possible to persuade the speech to fit almost exactly with the lip movements, by analysing the location dialogue (which, of course, does fit the lip movements) and processing the replacement dialogue to match. Wordfit, as originally developed, was a stand-alone system but is now available as a software option for SoundStation II.

To process dialogue with Wordfit, the location dialogue and the new dialogue are loaded into the SoundStation II. Wordfit analyses the new dialogue and the old dialogue in the same way and works out how it can make timing adjustments to the new dialogue to make it synchronise vowel for vowel and consonant for consonant with the original. It works in a roughly similar way to TimeWarp and either repeats small fragments of the speech or cuts them out and puts in a seamless edit.

Does it work? Yes, amazingly well. The demonstration I was given matched up some extremely sloppy replacement dialogue with the original perfectly. Apparently, it can also be used with a good degree of success on foreign language dubs. If Wordfit really does work consistently as well as I heard it in the demonstration, then every film and video studio should have one. Standards in this field of artistic endeavour are well due for an improvement.

PELICAN STUDIO

Rob and Ray bought a DAR SoundStation II as a post-production tool because, "We love the look of it and the way that it works. The way that you can not only hear what you are doing, you can actually see what you hear. You can actually look at a piece of audio passing before your eyes and make visual decisions about that audio."

Ray approves of its client appeal, too: "We have found that when we show it to clients, they like it as well. Instead of us talking an engineer's kind of language and the client being left out of it, they can look at the screen and say, 'Would that piece of audio go there, and that piece there?' You are all talking the same language, and they love it."

One of Pelican's more arduous sessions with SoundStation II lasted 28 hours, from nine o'clock one morning to one in the afternoon the next day. When the director realised that he could keep every take in SoundStation II, he did! They ended up with over 570 cues recorded, and at the end of the session there were around a hundred different takes that the director wanted to use. It seems that new technology such as the DAR SoundStation II is like the M25 motorway: as soon as it's available, people want to stretch it to the limit.

Publisher: Sound On Sound - SOS Publications Ltd.

The contents of this magazine are re-published here with the kind permission of SOS Publications Ltd.

The current copyright owner/s of this content may differ from the originally published copyright notice.

More details on copyright ownership...

Gear in this article:

Hard Disk Recorder > Digital Audio Research > Soundstation II

Review by David Mellor

Help Support The Things You Love

mu:zines is the result of thousands of hours of effort, and will require many thousands more going forward to reach our goals of getting all this content online.

If you value this resource, you can support this project - it really helps!

Donations for April 2024

Issues donated this month: 0

New issues that have been donated or scanned for us this month.

Funds donated this month: £7.00

All donations and support are gratefully appreciated - thank you.

Magazines Needed - Can You Help?

Do you have any of these magazine issues?

If so, and you can donate, lend or scan them to help complete our archive, please get in touch via the Contribute page - thanks!