Magazine Archive

Home -> Magazines -> Issues -> Articles in this issue -> View

Torch Song | |

From Schoolhouse To Multitrack | Torch SongArticle from Home & Studio Recording, February 1984 | |

In a special feature, Home Studio Recording takes a look at a group of young musicians, Grant Gilbert, William Orbit and Laurie Mayer, who have used their passion for recording to raise themselves above the level of 'bedroom' studios to the point of having their own complex 24-track set-up. Here Torch Song's Grant Gilbert explains the band's philosophy and gives some insight into how they have achieved such recording success, as well as taking us through the various stages of their studio's evolution.

'When I was at school I never considered myself as a producer of music, though I had always been an avid consumer of it. There was an awful lot of good music being played in London pubs at around that time, but the first person who really inspired me to start actually playing music was probably Eno, because he was the first one to show that you could make music without having had any formal training in it.

Both William and Laurie are accomplished musicians. William had been playing music on a regular basis ever since I'd known him at school, and Laurie was studying Music and Fine Art when I met up with her in Los Angeles. I went to America because I wanted to do something more adventurous than simply going to University, and I worked there for nearly four years as a photographer, and although during that time there was quite a lot of new music going on, neither of us felt there was really all that much that was inspiring, so we came back to England and that was when I met up with William again.

We moved in to a schoolhouse in Westbourne Grove that was due for demolition, and one room in that house became our studio. Because the house was rent-free, we found ourselves with sufficient money to buy a Teac four-track recorder and Roland Space Echo which formed the basis of our equipment line-up. We also had an HH PA system through which we could play occasionally in the school hall.

Since we had that equipment it became inevitable that we would get more interested in that side of things, so we started reading magazines on recording and talking to lots of different people who had more experience of different sorts of equipment. There was a problem in that we didn't know anybody else who was as interested in recording and electronics as we were, so we had to rely on doing our own research in order to get more information.

Our first mixer was a Tangent 12-4-2, with A-B switching on the outputs so that you could use it for eight-track recording even though you could only record on a maximum of four tracks at any one time. It's made by an American company from Phoenix, Arizona, and I don't think it's ever been seriously imported in the UK; but one model did come over for a show and was bought by a friend of ours who had an eight-track studio in South London. He sold it to us when he upgraded his equipment and I remember thinking at the time that it was the first piece of really professional equipment we had. It was a very, very good mixer, because it had very sharp, clean EQ controls, and good phantom powering and LED level indicators. The Tangent came under some very heavy use, so much so that when we came to sell it recently, there were quite a few things seriously wrong with it, like broken rotary pots and mute switches that were stuck!

Cassette Mastering

When it came to choosing a mastering machine, I chose a Nakamichi cassette-deck instead of the usual Revox, because we couldn't afford a reel-to-reel and a cassette recorder, and since cassettes were the medium everyone else was using, I went out and bought a Nakamichi 670ZX. It was a brilliant machine, and in fact it still is, because I've just got an Aiwa 770, which is supposed to be state-of-the-art, and even though it's got things like an LED real-time counter, it can't touch the Nakamichi for sound quality. I'm not so sure about the newer Nakamichis because they seem to be going more for the domestic market now, but we used to master on to the 670 with metal tapes and get some very good results.

I'm quite interested in hi-fi and read quite a few related magazines, so I'm aware that although the British companies like Linn and Naim and Meridian are very well respected, the Japanese dominate in the area of cassette-machines. The only alternative that I know of is the NEAL, and from what I've heard NEAL decks aren't all that great compared with, say, Nakamichi or Teac.

Our music was then very much improvised in form, and we recorded everything we did on four-track, mixing down on to stereo cassette via the Nakamichi.

After an abortive couple of months negotiating with a management company, Zomba, we managed to get a loan from the bank and upgraded our studio to eight-track. We found some premises in Maida Vale (which is where we're still living now) and moved in there. The previous owner had already converted the garage into a guest-room and we decided that would be the best place for our home studio.

Buying Secondhand

We also decided to buy secondhand equipment wherever we could, because that way it's possible to get better products for your money. So for instance we bought a Brenell Mini 8 tape-machine instead of something like a new Tascam, simply because the Brenell was a one-inch machine, and the signal-to-noise ratio with one-inch tape is so much better, it makes buying the equipment secondhand worthwhile.

We ended up buying all our equipment from Don Larking because he had a very wide selection of secondhand stock, and he was obviously interested in developing a long-term business relationship with us, given that we were keen on making the studio professional. We hung on to our original Tangent mixer and the Space Echo, but we also bought some more basic outboard effects, like a Great British Spring, and a Rebis modular system with a noise gate and a compressor/limiter.

Although the studio was still quite a basic set-up at this stage, what set us apart from a lot of other small studios was that we had a Roland modular synthesiser system incorporating the TR808 rhythm composer, an SH2 monophonic synth and a CSQ600 sequencer. When we decided to operate the studio on a semi-commercial basis, we advertised it with the Roland system included in the list of equipment, and about ninety per cent of people who chose our studio did so because of that facility.

Professional Work

Hiring the studio out to professional users gave William and I our first taste of working as engineers and producers, because very few of the people who came in to record knew the first thing about how to go about it. But the main purpose behind the studio was still as a means to produce our own music, and after a short while our compositions became more disciplined: it became possible to divide sections of our work into recognisable songs, but that didn't mean the studio became less important to us. In fact, I'd say the reverse was true because I know William for one spent almost all his available spare-time working on pieces in the studio.

The only real major problem was that we were almost constantly on the verge of bankruptcy, and during the year we had the eight-track system, we had to keep going to various different parties asking them to bail us out! Fortunately our confidence seemed to have a good effect on people and we had the advantage that since most of our equipment was secondhand, we could use it as a form of financial guarantee without the risk of it depreciating suddenly. The thing about buying all your gear new is that you lose money almost before you walk out of the shop...

Eventually however we realised that we needed a 24-track set-up in order to continue with our work, so I began a massive PR campaign and sent demo tapes to more or less every major record company in existence. I didn't bother with the independent labels because I knew they wouldn't be able to give us the sort of financial backing we needed. We were very surprised at the favourable reaction our music got, because we were at a disadvantage in that we weren't a gigging band, but a lot of companies seemed interested in us and the only problem in the end was choosing which one to go with and sorting out contractual details. Eventually we signed with IRS three months ago.

Demo Tapes

Sending tapes to record companies is a very long and random process. We sent cassettes to just about every company we could find, and sometimes it would be six months before the A&R people wrote back, by which time of course, our music had changed totally. To try and combat this, we sent tapes in under different band names, and I remember receiving two letters from PRT one morning, one rejecting us as 'Tiger, Tiger', the other asking Torch Song to come along for a chat.

When IRS got in touch with us and said they were interested, I honestly didn't know who they were, because I'd written off to so many major labels I hadn't really thought about independents at all. What I'd done was send tapes to just about every label in the Melody Maker yearbook, regardless of whether or not I'd heard of them.

IRS is owned by Miles Copeland who as you probably know is also manager of The Police, and he loved our tape as soon as he heard it. When we were invited up to the company offices to meet him he just said, "I want to sign you up. What do you need?" So we told him we needed a 24-track studio, which is no small thing to ask for, and we told him that because of the sort of music we were producing, we needed a good 24-track, not just the cheapest available. So we were talking about a lot of money for a lot of sophisticated equipment, and we were very surprised when he agreed to let us have what we wanted.

I think basically he realised that what we were asking for wasn't really all that much in relation to what we wanted to achieve. We told him that we were essentially a studio band and that all our evolution had been in studios, and what we really needed to do was to make an album to get all the material we'd already written down on to tape and then on to record.

What was so refreshing about IRS was that they seemed to have total confidence in the way we were going about things. A lot of the companies who expressed interest in us — like Phonogram, for instance — liked our music a lot but as soon as we said "we want to produce ourselves" they backed off. They refused to believe we were capable of doing the job ourselves and they refused to let us do it so early on in our career. They wanted to force another producer onto us, but obviously, because we were so interested in recording and because we'd been producing ourselves for so long at home, it was very difficult for us to accept that sort of thing.

IRS also saw the potential of our working with other artists once we'd got our own studio together. They saw the significance of our role as producers in our own right, independent of our own musical interests, which is quite unusual.

William Orbit at the mixing desk.

The First Release

Our first single is 'Prepare To Energize' which is a twelve-inch only. It's really only intended for the clubs; it's not really what you'd call a chart record. Of all the songs on our demo tape, it was the one that received the most favourable response, because a lot of people, like ourselves, are very excited by the new wave of New York dance music. We were very interested in that particular genre of music and we decided that we wanted to make some sort of contribution to it. Even though it's really completely different to anything else we've ever done, it's a very significant release for us because it was the point where we were trying out a lot of new musical and recording techniques. These included things like recording lots of sequencer patterns on different tracks and syncing them all together using a triggering device a friend had built for us.

It was also the first time we'd used the 24-track equipment, and for comparison purposes we put the original eight-track demo version on the B-side of the single. What is interesting is that both mixes are getting a very favourable reaction in the clubs, and if anything it's the original working that's proving most popular. What you've always got to bear in mind is that eight-track is perfectly acceptable for some sorts of music. Far too many people today assume that you've got to go 24-track in order to achieve anything like reasonable results, but that's a myth really.

I think the twelve-inch single is really a wonderful medium, because it enables you to put out an ordinary seven-inch version for chart purposes and do something totally different for the clubs. A lot of people nowadays are recording tracks as twelve-inchers and then editing them down for the seven-inch, which I think is perfectly healthy. The problem comes when musicians and engineers start doing things the other way; recording a short track and then padding it out for the twelve-inch simply because the latter has now become such an attractive commercial proposition.

Different Producers

What can also be interesting is that some bands are getting one producer to take charge of their A-side mix and getting another one in to do the B-side, which seems to me to be a much better use of the extra inches of vinyl than putting on a couple of previously unreleased bits of rubbish that nobody's interested in. You can look at the two mixes of the Human League's 'Fascination' single and the difference between the two is incredible, and it's also very interesting from a creative point of view. What you've got to say though is that that sort of mixing and editing only really works if the material is specifically intended to be dance music, because it's only then that all the different mixes are likely to be heard and appreciated. Often there are versions of tracks which are only sent to clubs as opposed to being commercially available on record, which I think is also quite exciting because it means that things are being recorded purely for danceability rather than to make money.

Outboard Equipment

When we went from eight-track to 24 we realised very quickly that our outboard equipment just wasn't good enough. Obviously it would have been possible for us to have carried on using that equipment and to have made an album using it, but in the end we had to make a decision about the quality of recorded work we were aiming for.

What I think has been very noticeable in recent years is the extent to which the Japanese have been applying themselves more and more to professional audio products. In a sense they've brought an entirely new philosophy to manufacturing studio equipment. When you look at something like the Otari MTR90 24-track machine we have, it's very evident that the makers have applied a lot of the technological lessons they've learned through making hi-fi and so on. If you compare our machine with something like a Studer, say, or an MCI, it certainly appears to be streets ahead in terms of the application of technology.

You can see it at the other end of the scale too with people like Tascam and Fostex. Because the Japanese approach to manufacturing is so different from anyone else's, it's pretty obvious that they're going to be the first people to come up with, say, applying cassette technology to professional or semi-professional recording, and they're probably the only people who are going to make much out of it either.

Much the same thing now seems to be happening with outboard gear. Obviously the Japanese companies aren't going to make much of an impact at the very top end of the market, because that's something they've never been all that good at, but they've started coming up with all sorts of budget equipment that nobody else can even approach, like the new Korg DDL, for instance.

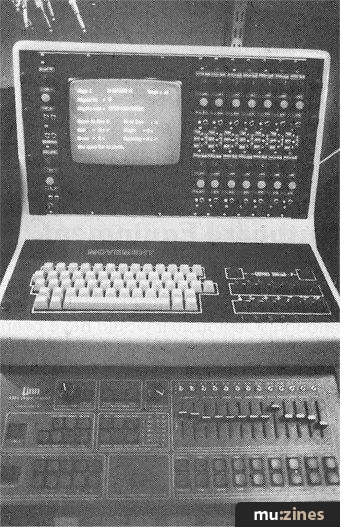

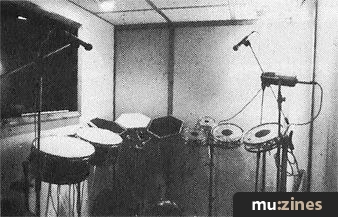

Once we'd got all our 24-track equipment together, we realised that we were going to have to spend more than IRS' advance in order to get all the musical instruments we needed to further our work, so we decided to start letting the studio out once again on a commercial basis, and to that end we bought a lot of instruments that many potential clients are familiar with, like a LinnDrum rhythm machine and a Roland Jupiter 8 synthesiser. We also had a friend of ours put CV outputs on to all our bits of gear, so that you can sync up all the rhythm machines we have, the Linn, the Movement, the Roland TR808, and some Simmons modules. That's given us a vast catalogue of electronic percussion sounds that a lot of people have found useful when they've come to the studio...'

More with this artist

Both Ends Burning (Torch Song) |

More from related artists

Torch Baring (William Orbit) |

The Heart Of The Bass (William Orbit) |

William Orbit - Urban Guerilla (William Orbit) |

Publisher: Home & Studio Recording - Music Maker Publications (UK), Future Publishing.

The current copyright owner/s of this content may differ from the originally published copyright notice.

More details on copyright ownership...

Interview by Grant Gilbert

Help Support The Things You Love

mu:zines is the result of thousands of hours of effort, and will require many thousands more going forward to reach our goals of getting all this content online.

If you value this resource, you can support this project - it really helps!

Donations for November 2025

Issues donated this month: 0

New issues that have been donated or scanned for us this month.

Funds donated this month: £0.00

All donations and support are gratefully appreciated - thank you.

Magazines Needed - Can You Help?

Do you have any of these magazine issues?

If so, and you can donate, lend or scan them to help complete our archive, please get in touch via the Contribute page - thanks!