Magazine Archive

Home -> Magazines -> Issues -> Articles in this issue -> View

Age Of Consent | |

Phil ThorntonArticle from Music Technology, October 1988 | |

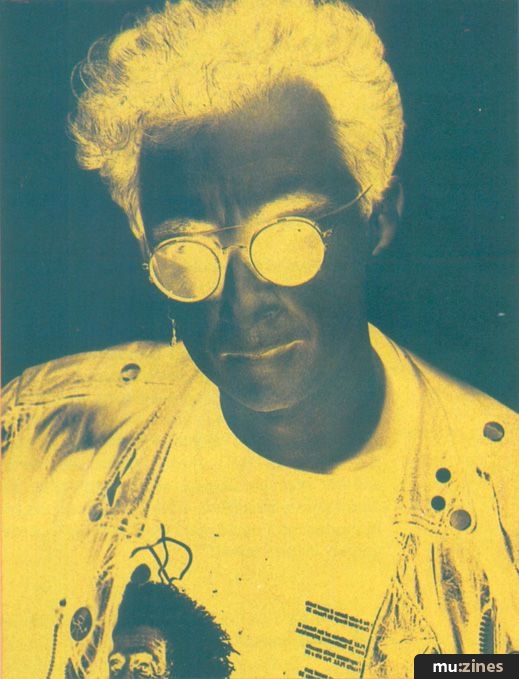

Through a career that has encompassed the controversy of the Bollock Brothers and the serenity of new age, Phil Thornton has drawn the best from technology. David Bradwell listens in.

Throughout a career that has embraced the extremes of Expandis, the Bollock Brothers and new age music, Phil Thornton has pursued technology for the sake of his art.

THE FIRST TIME I saw Phil Thornton was at the South Bank Purcell Room earlier this year. He was playing a track called 'Goldfish Don't Whistle' alone on stage, and thoroughly enjoying himself. Surrounded by keyboards, modules and sequencers he appeared to be in his element. The audience were there to witness the final night of Coda Records' new age festival. Thornton was the only non-Coda artist on the bill, and received one of the warmest receptions.

Meeting him now, several months later, he looks slightly different. Gone are the leather trousers; gone, in fact, are the synthesisers. At this moment we are in his living room, discussing music, colour and technology. After a few minutes, he suggests we take a drive to his studio. During the journey I catch up on his musical career so far.

A former member of synthesiser pioneers Expandis, Thornton attained further notoriety as a member of the infamous Bollock Brothers. It would be hard to imagine anything further removed from new age...

"I like light and shade", he explains. "I wouldn't want to just be vicious, I like to be mellowas well. Just prior to my first new age album Cloudsculpting, I was producing extreme hi-nrg. It was almost like getting an electric shock - Blancmange on acid, if you like. It was an analogue sequencer chugging away at high volumes with a very dicky bass drum and a slash of white noise and Hendrix-tvpe guitar. Over the last two years the public has heard the mellow side of my music. Now I'm quite keen to bring the old electric shock treatment back in."

Cloudsculpting was a soundtrack project, commissioned by publishers Filmtrax. The brief was to write an album of mood music, not to get too heavy, and not to use drums. For Thornton, who had previously been inclined to go over the top with drum programming, it was an intriguing challenge.

"It was actually quite inspiring to do something that wasn't rhythm based", he explains. "I was using quite archaic equipment, in particular analogue sequencers. I was given a week and a half to do it in, so it was quite mind bending but good fun. It was all written from scratch apart from one track which they requested called 'Goldfish Don't Whistle'."

The result was a classy debut reminiscent of early Jean Michel Jarre, though Thornton is keen to deny any direct influence.

"I like some of what he does, but I was trying to do that sort of thing before I'd even heard him. I sometimes resent people assuming that I'm influenced by him. Musically, my inspiration isn't from other people in the same field at all, it tends to be people like Jimi Hendrix or classical music."

Since Cloudsculpting, Thornton's intention has been to record one-off projects for different companies. The first of these was an album called Edge Of Dreams for hard-core new age label, New World Cassettes. They offered the composer a commission to produce a single piece of music, stretched over two sides of a tape.

"I wrote an epic for them", Thornton says. "The technology was greatly different to Cloudsculpting, being basically a QX1 triggering a TX816. The engineer was the guitarist from The Enid, who I've known for years. It was great to collaborate with somebody who was in tune with what I'm doing musically as well as being very experienced at the technical side of it. He set up the sequencers to record a segment and then I'd play something or make a suggestion. Over the ten days I was there we developed a vast labyrinth of sequences and sounds. Most of the melody lines were actually played, but the sequencer lines were all meshed together and then we pulled things out in the mix."

WE'VE REACHED Thornton's Expandibubble studio and, once inside, the conversation turns to equipment. His aim, he says, is to combine the best of old and new technology, a claim borne out by the equipment surrounding us. In the Korg corner an SQ10 sequencer nestles beside MS20 and MS50 synthesisers. Below them is an Atari 1040ST, complete with Pro24 software, a Mirage, DX7 and Moog Source. Thornton offers his comments on playing techniques and polyphonic synthesisers.

"My main love is synthesisers and for most of my career, a synthesiser was an instrument which only played one note. There's not a lot of point in having a good left-hand technique if that's all you play. I bought the DX7 when it came out but I've bypassed analogue polysynths. To me they were not serious instruments. I bought an Elka Rhapsody when they came out, and I put that through the filters of the Korg MS20 and MS50 under the control of an SQ10 sequencer. As far as I was concerned, that was as near to being a polysynth as you could ever want. In general, my approach is not to sit there with a chord sequence going on, I prefer to work with melodies and counterpoint. Consequently, polysynths have never been a crucial part of my setup. With the system I've got now I can sync to tape, and control 99% of the electronic music capability in this room through the computer. For most people I would say a computer system is not necessary because you could do the same thing on a QX21, but then, when you get in to the bigger studios you have to be compatible. As for the newer keyboards, the DX7's great. It has got limitations and there's lots of things it should be able to do but can't. I know plenty of people who've sold DX7s because things like the D50 come out, but for me, a D50 will never be as much fun to program as a DX7."

Programming is something Thornton does a lot of, basically because he enjoys it. He rarely starts with a preconceived idea for a sound, although he believes that's where the skill in programming lies.

"The fun is in just keeping your ears and your options open. I might have a programming session where I'll start off with no preconceived ideas, maybe pick a sound I'd recently come across that inspired me, then sit and analyse why it inspired me, and work towards making it inspire me even more. I suppose, once in a blue moon I will do something from scratch, if there's a particular sound which I just have to have, but it can take two days to create a sound. It's not an easy thing to do, although I love doing it.

"I'm into the Mirage these days, and I've been using the Akai S900 quite a lot. More often than not, I use the Mirage as an analogue synth, because the filters are very sweet on it, they're very reminiscent of a Moog. I've made quite a few samples of string quartets on the Mirage which, when you play them as string quartets, are pretty raspy and noisy. But if you put the resonance right up on the filters and treat it as a Tangerine Dream-type swell it works brilliantly. As the filter goes through the noise inherent in the sample, it has a flanging quality that doing the same thing to a good sample of strings wouldn't have. Doing the same sort of thing to drum sounds is quite interesting, too."

When it comes to sampling morality, Thornton's attitude is dictated by his view of music as art.

"I know plenty of people who've sold DX7s because things like the D50 come out, but for me, a D50 will never be as much fun to program as a DX7."

"One of the things about the hip hop scene and rapping that I'm quite inspired by is that there's no morality involved, it's purely an artistic thing. If you take two bars of a James Brown riff and cycle it round and round, you've already changed it. It's no longer a James Brown riff as he intended it. Soon there will be equipment which can sample whole songs, but I don't know if there would be any point in doing that. It's a bit weird when it comes to snare drum samples because most sounds in rhythm boxes are sampled. That sample has got to come from somewhere and we've only got Roland's word for it that they put a snare drum in a studio somewhere."

ON STAGE, THORNTON complements his range of synthesisers with an electric guitar. In some ways he sees the guitar as his first instrument, not because he is most proficient on it, but because it is the instrument that inspires him the most. From there it may seem a logical step to the MIDI guitar synthesiser. Surprisingly, this is not the case.

"If I had the money I'd buy one, but I'd prefer to put an advert in the paper and find someone who inspired me with the way he played it", he explains. "Using a guitar synth to program a sequencer is not crucial to what I do because I don't like the idea of using a sequencer as just a recorder. I think its strength lies in that you can manipulate things and make them sound robotic or natural. If you're going to play a solo you might as well switch your tape recorder on and play a solo. The Clavinet is the only keyboard instrument I've ever come across which even comes close to the physical vibration in your fingers you get with a guitar.

"One thing I've noticed about the way most people use MIDI is it's too easy to just layer things. That's not a very musical way of creating a thick sound, because everything is consistent. If you hit one note harder then all the synths that are slaves will play that note louder which is not something that would happen naturally. MIDI is a great thing, but it has meant that you can be superficially impressive. It has detracted from what making music really is about, like putting in soul and feeling. Producers don't hire specialist musicians to play synthesisers in the way they used to, because now they've got a computer and a rack of MIDI gear. It produces a sound that's fine for the record, but nothing to do with music."

Thornton's enthusiasm comes to the fore, however, when discussing new possibilities technology has opened to him.

"The fact that I can now plug a sophisticated computer-based sequencer into my old MS20 is the most exciting thing that's happened to me in years. One day I'm going to have the most under-the-top computer setup you'd ever believe. When I've sussed this set of gear, I'm thinking of using the Pro24 as the control centre and having another computer create music artificially, like Jam Factory on a Mac. Then I would run the two in tandem so I could start from nothing and very quickly inspire myself."

AWAY FROM THE technology, Thornton sees himself as a musical pioneer.

"In the way I try to create emotion and feel through the use of the equipment. I'm definitely out on a limb", he explains. "I don't collaborate with anybody else, so just by the nature of things I have to be unique. I break rules - I find out how people do things and then go out of my way to do them the opposite way. I love that feeling when you break the rules and come up with something unique. I like working with other musicians and doing the same things with them, almost treating them as pieces of equipment. I don't mean that in a derogatory sense, but rather than scoring something out for someone and telling them to play it, I might play mind games with them and deliberately miss out part of the puzzle. They don't know the whole picture, so then I can take what they saw as an input.

"There is a serious side to synthesisers that a lot of people don't understand. You're dealing with electrical energy to do something artistic, which at its best creates its own energy. The relationship between those two types of energy is very often missed. That side of music and the relationship of colour to music is something I'm intrigued by. Not just the colours, because that's just a certain band of energy. It comes back to what I was saying about manipulating electricity. The same thing applies when utilising colours for inspiration. Numbers can do the same thing. You can take a simple time signature like 7/8 which for most people signifies jazz rock, but you can actually create some unique feels just by taking the number itself seriously. I'm working towards getting as much knowledge about the serious side of new age as possible, not in a cold clinical way, but because I'm actually interested in it."

Thornton belives he has completed the equipment goals he has been working towards for the last two years. Now he is no longer on tour and has time to compose music, he is beginning to doubt the wisdom of his original plans.

"The aim I had with the equipment was to be able to write exclusively on the computer, so I'd got maximum control of the composition side, and then take the disk into a studio. I've now realised that approach actually misses quite a lot of what the creative side of composing entails - collaboration with other people. Just getting a guitarist in means that there are a whole load of opportunities that are missed when you're working on your own with a computer. What I'm going to end up doing is putting ideas down on the computer and taking those into the studio and then bringing in session players. A lot of the things on Cloudsculpting were happy accidents. There's a solo where I'm playing the synth backwards which is something that you'd never really do on a computer in such an inspiring way. It's all very well to play a 'railroad track' solo, where it's over a riff rather than a chord sequence, and then tell the computer to turn the whole thing inside out so that the first note is the last note, but that's not the same thing as turning the keyboard round and actually playing it backwards. That's much more inspiring because it's actually there in front of you. Your fingers can't fall into the old cliches."

Thornton's latest project is a live album entitled Forever Dream. It was recorded at a concert in Scotland at which he was backed for the first time by other musicians. This he describes as a great leap forward.

"I was able to conduct people with an actual feeling for electronic music. I had a didgeridoo player in the team as well. The first gig I ever did playing new age music was at an arts centre in Newcastle. Twenty minutes before I went on stage I went into the dressing room and there was a guy there playing a didgeridoo. I was so impressed with the situation that I changed my set so he could come on stage and play with me. I never found out his name or anything, and I'd never even seen a didgeridoo in the flesh before, but it was just so perfect. That is my philosophy - whatever comes up in front of me I'll be positive about and use."

Driving back to Thornton's home, the composer reviews the past couple of hours, and displays an acute sense of modesty.

"A lot of my time I live a very hermit-like existence and I don't talk to people." Collapsing in fits of laughter, he adds "Being in a small room with synthesisers for long periods of time can drive you completely round the twist. If it wasn't for synthesisers I'd probably be alright."

Publisher: Music Technology - Music Maker Publications (UK), Future Publishing.

The current copyright owner/s of this content may differ from the originally published copyright notice.

More details on copyright ownership...

Interview by David Bradwell

Help Support The Things You Love

mu:zines is the result of thousands of hours of effort, and will require many thousands more going forward to reach our goals of getting all this content online.

If you value this resource, you can support this project - it really helps!

Donations for April 2024

Issues donated this month: 0

New issues that have been donated or scanned for us this month.

Funds donated this month: £7.00

All donations and support are gratefully appreciated - thank you.

Magazines Needed - Can You Help?

Do you have any of these magazine issues?

If so, and you can donate, lend or scan them to help complete our archive, please get in touch via the Contribute page - thanks!