Magazine Archive

Home -> Magazines -> Issues -> Articles in this issue -> View

Oscar Synth | |

Article from One Two Testing, January 1985 | |

Britain's finest (only?) mono

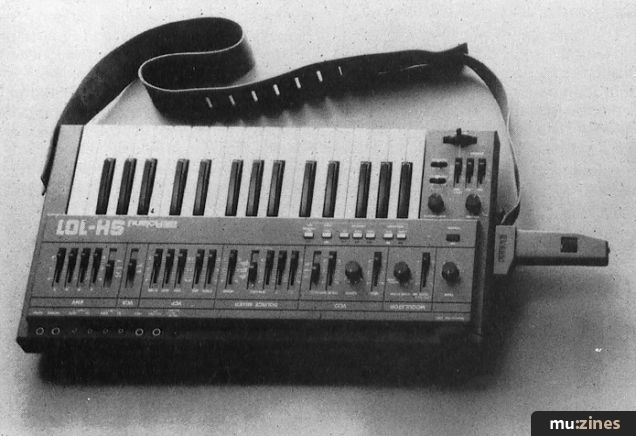

TO BE BLUNT, it looks like a tyre tractor. Uncharitable, perhaps, but what else can you make of those thick rubber ridges separating the control sections, not to mention the slabs of Firestone's finest that make up the end cheeks.

Yet think back to granny's famous words as she bounced you on her digital knitting, scarf-o-master... 'judge ye not a synthesiser by its external decorations'.

For the Oscar is excellent, imaginative, innovative, packed solid with features and details very rarely found elsewhere and, perhaps most important of all at a time when synths are being brewed to near identical Japanese recipes, it's British, and it's different.

The Oscar began life as virtually a one-man operation in 1982. Software and hardware were the creation of Chris Huggett who easily qualifies as being 'very clever', but had the limitation of taking on the recognised, big business synths with naught but his own bare soldering iron. Though the Oscar can look like a synth that's 'growed' as opposed to being perfected in a mighty R&D department, it's a tribute to designer and machine that the instrument has achieved considerable popularity through word of mouth, and has survived to become a mark seven.

So we have a MIDI-equipped, programmable, 32-sound, monophonic synth boasting two digital oscillators, plus the ability to devise its own waveforms by adding up to 24 harmonics to the fundamental.

On top of that there's a 1500-note step time sequencer. That figure is the total memory space which can be divided into 12 separate sequences (255 notes is the longest) which can in turn be linked together for more involved arrangements and stored in 10 chain positions.

Notice the words digital oscillator there, not digitally controlled oscillator. T'is true, the pair that nestle within the Oscar are, like the rest of the treatment circuitry, 'electronically imagined'. They exist in software only so Z80 processors essentially calculate what sound an oscillator would produce, were it to be fed through a filter of this type, at just such a setting and given an envelope of this shape, etc.

But don't down-mag with the impression the Oscar can create only the clinical and metallic noises associated with digitallity. Far from it. It's a winningly thick and forceful sounding synth, equally at home with broad bass sounds or innocent and appealingly dirty solo tones. The variety of noises the Oscar can produce is immense, both in terms of fine tuning sounds by playing with the waveform construction, and in coming up with patches that go several steps further than the capability of a normal analogue.

The Oscar updates have largely been in the software (existing samples can therefore enjoy these advances by dropping new EPROMS into old sockets). This does mean that such improvements must work with the existing front panel and controls, so to save on space, the keys themselves frequently double as switches.

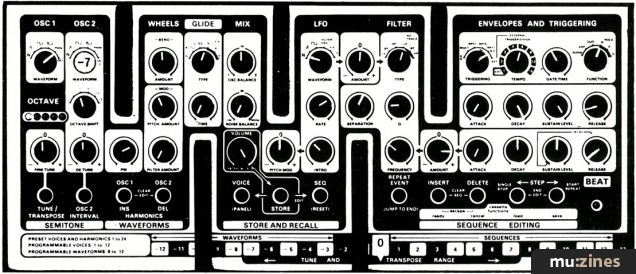

The Oscar's panel zig-zags around those aforementioned rubber dividers. First section past the left end cheek (wherein is secreted the on/off switch) we have the two oscillators both of which feature preset triangle, sawtooth, square, pulse, and pulse width mod waveforms.

It's possible to turn Osc 1 off or coerce Osc 2 into adopting the same waveform as Osc 1. The pulse width modulation rate is preset but at slightly different speeds for each oscillator — very sensible considering we're all after slow but indefinable pulse width 'munges' which the Oscar aspires to admirably.

A five-strong line of LEDs just below the oscillator controls serve many display purposes, most obvious is to indicate the octave selected by up and down buttons to the left of the keys.

Osc 2 can be moved away from Osc 1 in small, chorusy amounts (detuned), and by striding octave steps or harmony intervals invoked by pressing the 'interval' push button and then the keyboard key matching the desired harmony. (You can also transpose the entire keyboard in this manner.) Lurking nearby are a balance control between the oscillators and the noise source, a six-position rotary switch for various portamento options — normal, auto (gliding only when two notes are held down) and glissando plus the same trio again at useful, fixed rates instead of the infinitely variable (and programmable) alternatives of the first three.

A word now about these programmable waveforms. If you're used to the strong tone changes of swapping from, say, triangle to square, the Oscar's wave composition might seem slow and fussy, the tone barely changing as you tack on new harmonics. Have patience, the results will be varied, but will take time.

First step is to clear one of the five waveform memory positions to zero giving you just the pure fundamental sine wave, best heard by playing a low note with the filter open, a low resonance and the output set to hold. The editing section supplies insert and delete buttons. Press insert, and then, for example, the D key one octave up from the bottom (corresponding to 2 on the front panel scale). You have now added a sine wave at the second harmonic to that fundamental and should hear the sound become richer and slightly brighter. Each harmonic has a mildly different effect (to be truthful they get hard to tell apart in the upper regions). The fine tuning of the sound is more down to the strength of harmonics you insert since each is programmable at 16 volume steps — you'd achieve maximum by pressing the D 16 times.

Each oscillator can be programmed with its own waveform and you're free to treat them with filters etc, as normal. Seems a pity to transform them too strongly. With the right programming they already stand out as spikey, chiming or organ-like, distinct from the usual analogue tones. But the choice is yourn, and great it be.

Slipping around to that filter by way of the six-position LFO (triangle, ramp, square, filter envelope, keyboard and random) the Oscar's ability to take standard analogue formats one step further is again reinforced. It's a 24dB per octave filter available in low, high and bandpass modes with or without keyboard tracking.

The Oscar actually has two 12dB per octave filters which can either be kept in step for the 24dB effect (the punchiest form of filtering) or their cutoff frequencies can be separated by up to four octaves. That separation lets you to take two bites at any source waveform setting up not one but two resonances in the sound. Aurally the effect is of a patch with less of the familiar 'wang' over a wide range, but more as though it were being caged in between two frequencies — a sound concentrated and pulled it on itself.

If you're used to commonly accepted 24dB filters the Oscar's solutions might at first seem gimmicky. First encounters with parametric eq can leave similar impressions. Experimentation will prove otherwise.

The efforts of the Oxford Synthesiser Company return to earthier levels with the two ADSR envelope generators, which I found the only slight disappointment on the Oscar. Both could have been a fraction snappier. Some synths like Korgs and Rolands, begin their notes quickly when you hit the keys. Others, such as the early Moogs and Oberheims, feel as if they begin a split second before you touch the keyboard.

The Oscar's ADSRs are punchy enough, slugging it out easily with other popular makes, but they don't quite get... er... angry.

Tinkerers that OSC are, they couldn't leave the envelope generators completely alone. The S and R sections of the Filter's generator encompass a delay function. When the sustain is set at zero, a slight hiccup is deliberately introduced to the tail end of the sound so the filter blips as it dies away. The release control determines how long after the initial decay this blip takes place, it's only short but it's another Oscar detail to be played with when you're searching for that sonic identity of your own.

All this discussion of facilities has overshadowed the feel of the Oscar.

The three-octave, plastic keyboard is reminiscent of several other early British synthesisers. It's lightly sprung with neat, well spaced keys, that have a fully enclosed, sloping underneath at the front. (Complicated, that.) They're also creamier than the usual whiter-than-white Japanese keyboards.

Even more individualistic are the pitch and mod performance controls, both on chunky rubber wheels and with the heaviest spring action I have ever felt on any synthesiser. They virtually leap back into the centre-off position. You'd never need worry about their safety during an over-active gig. They are a fraction close to the tall, rubber surround at the end of the synth, however, and it's no easy job to squeeze your fingers around them. Best to rest them on top.

Just to the right are the octave selection buttons (two octaves up and two down) which are conveniently placed and fast to use. Take a cookie from the cookie jar. The voice selection system needs a little more adapting to. You press the 'voice' button in the centre of the front panel and then push down any one of the keyboard keys between C (one octave up from the bottom) and the C at the top. These, according to the scale on the front panel are for programmable voices 1 to 24. You'll hear nothing, but the next time you play the keyboard, it will be producing that selected voice. Keys 1 to 24 correspond to the Oscar's sounds — a factory selection of sustaining and slapping bass voices, a couple of solo brass and trumpet options, one or two pipe and jazz organ tones (which are less successful in mono than they would be on a poly) plus an exceptionally fine imitation of a high, flutey, Mini Moog patch as frequently applied by Keith Emerson in the fade outs of early ELP tracks.

The Oscar has previously been compared to the Mini Moog. It's not too unfair a comparison. The Mini Moog was unavoidably more erratic than this modern, digital offspring, and sometimes more 'human' because of it.

The remaining bottom octave of keys are the spaces for the other 12 programmable voices and are numbered -1 to -12 which is perhaps slightly too O level maths. However, it's laudable that everything on the Oscar is programmable (barring the final volume) and this includes detune amounts, modulation depth, selections for the pitch and mod wheels, etc.

With all this finesse and achievement packed into the Oscar, I was (unreasonably) expecting a slick, real time, easily programmable sequencer. It is asking a bit much. The Oscar's is a straight step time job, entering the notes as events one at a time by pressing the appropriate keyboard key, and then storing the timing as normal, legato or tied depending on how the key is released and what other buttons are pressed. I found the number of commands and double presses required were daunting to begin with. Doubtless they'd become practiced procedures.

In its favour there are several valuable insert, delete and edit functions allowing you to replace notes, or, when several sequences are chained together, to add extra sequences or swap voices at desired stages. Also liked the jump functions that let you instantly reach the beginnings or ends of sequences without plodding all the way through them, note by note.

Criticisms are hard to find. Perhaps the Oscar is at times over complex in use such as the extra buttons that have to be punched to change the direction of the arpeggiator, and the 'small caution' that the same operations could also start the sequencer so to avoid that you also have to etc, etc, etc.

But those are finicky faults and not much to worry about when the trade-off is the remarkable degree of fine control the Oscar allows. You really do feel you can get right inside the sound and mess about with it, from the original waveform construction up to how, when and why the filter behaves.

If you're looking for any synthesiser then it could be argued that for the price of the Oscar you could pick up a perfectly presentable programmable polyphonic — second hand in the case of certain models, new in the case of others. Incidentally, as a final fascination, the Oscar is equipped to be duophonic.

However, if the decision is less complicated, if you're just looking for a monophonic synth it would not be stating the case too strongly to say right now, at this price, the Oscar simply has no competition.

OSCAR mono synth: £625

Contact: Oxford Synthesiser Company Ltd., (Contact Details).

Also featuring gear in this article

A Selective Survey of Lead Line Synthesizers

(ES Sep 83)

OSCar Synthesiser

(EMM Aug 83)

OSCar Update - MIDI OSCar

(ES Jan 85)

The Oscar

(MU May 83)

Patchwork

(EMM Jan 85)

Patchwork

(MT Mar 90)

...and 1 more Patchwork articles... (Show these)

Browse category: Synthesizer > OSC

Featuring related gear

Browse category: Synthesizer Module > OSC

Publisher: One Two Testing - IPC Magazines Ltd, Northern & Shell Ltd.

The current copyright owner/s of this content may differ from the originally published copyright notice.

More details on copyright ownership...

Review by Paul Colbert

Help Support The Things You Love

mu:zines is the result of thousands of hours of effort, and will require many thousands more going forward to reach our goals of getting all this content online.

If you value this resource, you can support this project - it really helps!

Donations for September 2025

Issues donated this month: 0

New issues that have been donated or scanned for us this month.

Funds donated this month: £0.00

All donations and support are gratefully appreciated - thank you.

Magazines Needed - Can You Help?

Do you have any of these magazine issues?

If so, and you can donate, lend or scan them to help complete our archive, please get in touch via the Contribute page - thanks!