Magazine Archive

Home -> Magazines -> Issues -> Articles in this issue -> View

Using Microphones | |

Directional CharacteristicsArticle from Home & Studio Recording, June 1984 | |

An explanation of the 'directional characteristics' of microphones.

A microphone's response to sounds from different directions is completely different from that of the human ear. Hearing involves some information telling us from where a sound comes. Our brain assesses the time delay between the left and right ear's perceptions due to unequal sound paths, (except when the sound source is exactly in front of or behind us) and utilises this information to locate the sound source. Recent studies have shown that directional information is also gained by one single ear, using reflections from the ear's pinna (lobe).

A subtle psychoacoustic mechanism also enables us to shut out unwanted sounds from directions other than our 'target', creating a way of focusing our attention on one particular sound. This is not true of a microphone.

Figure 1. A hypercardioid mic allows doubled distance to the target instrument, with same ambient sound pick-up, compared to an omni.

A microphone won't provide any directional information. It simply reduces sound pick-up from directions off its axis (unless it's an omni), but it will still pick up this sound, though to a smaller degree. Figure 1 shows how rejection of ambient (off-axis) pick-up allows greater distance to the instrument to be recorded. It is important for the home recordist to keep in mind that, in a well-damped recording location with little reverberation, pick-up of unwanted ambient sound (leakage) may be reduced:

a) by selecting a more highly directional microphone

b) to a much higher degree by moving unwanted sources further away from, and the target instrument closer to, the microphone.

Polar Diagrams

To get an idea of a mic's directional characteristic, it is useful to rotate the mic in front of a speaker to which it is connected. By pointing the microphone right at the speaker you'll get feedback even at a long distance. Turning the mic around makes it possible to move closer without feedback, thus giving a good impression of how the mic 'hears'. (Turn up the microphone gain slowly though, for your ears' sake.)

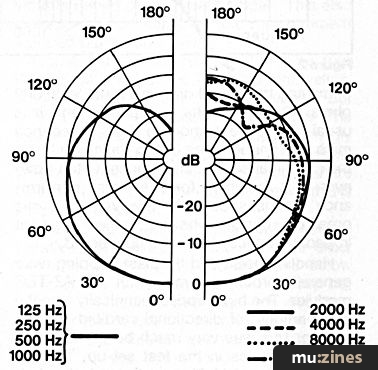

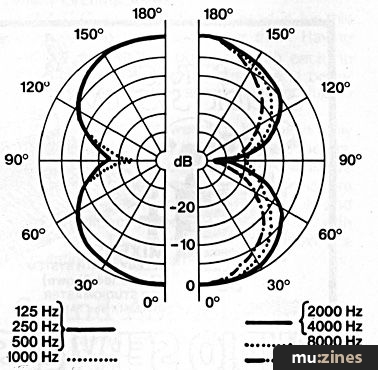

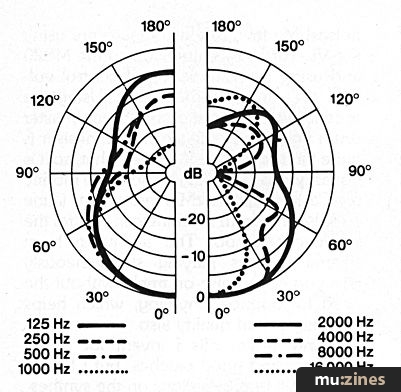

An alternative means of assessing the directional characteristic of a mic is to study the polar diagrams issued by microphone manufacturers. These show the attenuation values for each particular angle from the mic axis, as well as for different frequencies (directional response is frequency-dependent!). Because of the left-right symmetry of the curves (attenuation is equal for a specific angle to the left, right, up and down) some manufacturers divide the graph into two semi-circles showing 3 or 4 frequencies each. But always bear in mind that polar response is three-dimensional!

Polar Problems

The standard polar response measuring distance of 1 metre in no way represents the usual close-up situation. If a singer stands close to a mic, reflections from his/her face, screening effects of the head etc. all alter the polar response tremendously. On the other hand, for long working distances, off-axis alternation at low frequencies is better. (A sort of reversed proximity effect reduces bass off-axis attenuation if measured at 1m.) Still, polar plots do indicate the basic directional performance. Figures 2-6 show the most commonly used directional patterns.

Figure 2. Omnidirectional: equal sound pick-up from all directions; at high frequencies tendency to cardioid (sometimes fig-of-eight) pattern.

|  Figure 3. Cardioid: greatest sensitivity at 0° (directly in front of the mic), greatest rejection at 180°.

|

Figure 4. Hypercardioid: greatest sensitivity at 0°, greatest rejection at 135°, good rejection for signals from the side (90°).

|  Figure 5. Figure-of-eight: greatest sensitivity at 0° and 180° (in front and behind the mic), greatest rejection for sounds from the side.

|

Figure 6. Shotgun mic: special design for very narrow pick-up angle and long 'reach'; rejection of off-axis signals to aim the mic at a distant source.

|

Quality

As mentioned before, directional characteristics depend on frequency. Good quality microphones display a rather uniform polar response throughout the frequency range. And here is why you need it: as off-axis sound pick-up will be attenuated, but never totally suppressed, there will always be sound leakage (especially strong in a live concert). By rejecting leaking signals more strongly at certain frequencies than at others, you'll get nasty colouration. At this point, leakage becomes really annoying. Uniform directional response over the whole frequency range is displayed in a 'tight' polar plot - with curves that don't differ much from each other.

Acceptance Angle

For recording purposes, in the studio as well as in a live recording situation, there is often a need for a microphone with a wide acceptance angle either to cover a large instrument (grand piano) or ensemble, or musicians who keep moving about. Top cardioid microphones (Neumann U87, U47, AKG C414, EV RE20) or PZMs are renowned for their wide acceptance angle assuring a wide, open sound.

Of course, omnidirectional mics will suit this job nicely. They are often overlooked by the recording novice, although they can provide a good solution at a decent price.

Avoiding Feedback

For live applications, especially for vocals, the main microphone requirement is for good suppression of off-axis sound pick-up (from monitor speakers mostly) to ensure maximum gain - before feedback. With super feedback safe microphones (mostly hypercardioids like the AKG D330) your trade-off will, of course, be a pretty narrow sound acceptance angle.

Anyway, here are some hints for preventing feedback:

• Aim your monitor speakers in the direction of the mic's greatest rejection: 180° for cardioids, but about 135° for hypercardioids (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

• If you use sidefill monitor speakers, go for hypercardioid microphone types (greatest rejection at 90°).

• Watch out for sound reflective surfaces that might reflect sound from the monitor speaker into the microphones' most sensitive area. This is very often the case in acoustically untreated rehearsal rooms.

• As a singer's head close to the mic can change directional characteristics, feedback often occurs while not singing and moving away from the mic. Switch off the mic in this case. If the mic doesn't have an on/off switch use an XLR connector with an integrated switch (available from Neutrik), or simply build one yourself. I once saw a dance band who wired easy-action light switches into the mic cables, at positions within convenient reach of the musicians.

• For speech reinforcement, shifting the output frequency with a harmonizer will increase gain-before-feedback by about 8 dB.

• Use fewer microphones; each additional mic, amplified with the same gain, will cost you 3 dB gain before feedback.

Response Uses

Omnidirectional microphones give a nice open sound. Terrific for acoustic guitar, piano, miking of reverb chambers; also try them for other instruments. Omnis are also used for all measuring, calibration etc. of microphones/frequency plots.

Figure-of-eight responses are ideal for recording singers or instrumentalists, who can be positioned facing each other, eg. backing singers (Figure 8). Hypercardioid types are used when sound leakage of closely-spaced instruments cannot be reduced by moving instruments away from each other, eg. for hi-hat or snare drum.

Figure 8. Using the figure-of-eight polar pattern to pick up backing vocals.

Shotgun microphones, designed for long microphone distances, are seldom used in the sound recording studio, but are regularly utilised for wildlife recording and sound effects.

Cardioid types, of course, are the usual choice for most recording applications.

Multi-Pattern Microphones

Some excellent studio mics (Neumann U87, AKG C414) offer 4 different patterns. They utilise 2 parallel diaphragms, their output being electrically combined. As one works as an omni, the other as a figure-of-eight, different polar patterns can be 'synthesised'. However, as a small trade-off, these particular polar patterns may not be as 'tight' as with a single-pattern microphone, but can represent a good compromise.

More with this topic

Room To Roam - Radio Microphones |

Mikes And The Mechanics |

Rhythm methods - Drum recording guide |

What Makes A Mike Right? - Microphone Tips |

Feedback! - Why It Occurs & How To Prevent It |

Miking Music |

Live Wire - Miking Up |

Practical PA - Part 1: Introduction To PA (Part 1) |

Basic Microphone Technique |

Sound Bites - Production Tips & Techniques |

Live Miking - Drums |

Looking at Microphones |

Browse by Topic:

Microphones

Publisher: Home & Studio Recording - Music Maker Publications (UK), Future Publishing.

The current copyright owner/s of this content may differ from the originally published copyright notice.

More details on copyright ownership...

Feature by Wolfgang Staribacher

Help Support The Things You Love

mu:zines is the result of thousands of hours of effort, and will require many thousands more going forward to reach our goals of getting all this content online.

If you value this resource, you can support this project - it really helps!

Donations for April 2024

Issues donated this month: 0

New issues that have been donated or scanned for us this month.

Funds donated this month: £20.00

All donations and support are gratefully appreciated - thank you.

Magazines Needed - Can You Help?

Do you have any of these magazine issues?

If so, and you can donate, lend or scan them to help complete our archive, please get in touch via the Contribute page - thanks!