Magazine Archive

Home -> Magazines -> Issues -> Articles in this issue -> View

Article Group: | |

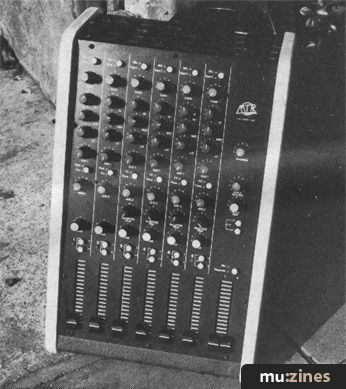

MTR 12:8:2 Mixer | |

Studio TestArticle from International Musician & Recording World, August 1986 | |

Jim Betteridge explores every nuance of the MTR mixer, but still doesn't reveal what MTR stands for

This is the Mark II version of the MTR 12:8:2 mixer. I feel particularly well qualified to give forth on this device because I have had sustained personal experience of the original. At under £500 the Mark I seemed to be the proverbial real bargain, but in practice the corner cutting effected to arrive at this phenomenally low price left a rather weak and imbalanced product.

Back From The Drawing Board

One of the many fine qualities of the MTR A&R department is that they listen to constructive criticism and are always open to improving their products. Such an approach always wins out in the end and the MTR brand is not without its winners. Thus I was pleased to hear that the MkII 12:8:2 had surfaced after the rather severe shelling suffered by its predecessor, and still at an enticingly low price.

As the name suggests, the mixer has 12 input channels, eight output groups (making it ideal for eight-track recording) and a final stereo output for mixdown and monitoring. It's a reasonably compact console which it achieves through an in-line design which will be explained later. Much of the basic layout is identical to the original: at the top of each input channel is a Mic/Line button which switches between the balanced XLR mike socket and the ¼" mono (unbalanced) line level jack socket. A single input gain control determines the level at which the signal is sent to the input of the eq section. A large red LED further down the channel acts as an input peak overload indicator, lighting up 4dB before clipping to warn you that you may be about to overload the equaliser.

Speaking of the equaliser, though many things have been changed for the better on the new model the old fixed three-band eq section remains. For me this came as a serious let down; the general standard of the MkI desk made this arrangement fitting, but with the general upgrading that's gone on here I feel that it now rather lets the rest of the system down. I can just see the designer pulling his hair out at this remark; balancing features against cost isn't an easy task, and the skill is knowing where to draw the line. Whatever's improved, there's always apparently a weak point somewhere to be jumped on. An inexpensive mixer is bound to have to suffer some compromises, but if you are to have reasonably hassle-free, high quality recording there are certain facilities that are a must. I find fixed three-band eq very limiting; you can't pull out unwanted rings and resonances, give a hard edge to a tom, or bring out the tone on your Rhodes sound... in other words you can't use your ears or imagination to determine how you colour a sound. A sweepable mid control would go a long way to putting this right, and indeed very few even semi-serious recording mixers don't have one. It would naturally up the price a bit, but the difference would be considerable. After all, all the routing and metering in the world is of little use if you can't get the sound you want.

There are two auxiliary sends, one fixed post-fade and one switchable pre and post. The first is intended as an effects send while the second can be used pre-fade as a foldback control while recording, and post-fade as an extra effects send during mixing: a faultlessly sensible arrangement inherited from the original. Below the aux knobs are to be found the routing buttons and their associated pan controls. There are five routing buttons: 1-2, 3-4, 5-6, 7-8 and L-R, allowing routing to all eight groups (ie the eight tracks of the multitrack) and the main stereo outputs for mixdown. Odd tracks are accessed by panning to the left and even tracks by panning to the right. A fifth button is marked PFL, meaning pre-fade listen. Pushing this button effectively (though not actually) mutes the rest of the channels so that you can listen to one instrument, or a selection of instruments, in isolation. To the right of the console is a suitably large LED to tell you when a PFL button is depressed.

Back To The Design

And so we return to in-line design and the resultant compactness mentioned earlier upon which I promised to expand. The term 'in-line' simply means that rather than having a separate monitor section tacked on the end for the monitor controls, they are all incorporated in the main input channels. Being designed for eight-track work, the console needs eight tape monitor channels. Hence, on each of the last eight input channels you will find a dual concentric control for monitor level and pan which correspond to tape channels one to eight.

In the normal home recording environment, it is unlikely that you would want to record using more than four channels at once, except on the first backing track where you might want perhaps six channels for your drum machine alone. There is a small problem here in that the line level sockets into which you plug the multitrack returns (the playback from the multitrack) are the self same sockets into which you would want to plug your drum machine. Only channels one to four are unfettered by tape returns; if any more line-in channels are required at any time you have to unplug some. This doesn't generally raise any unsolvable problems — you simply start from channel 12 and work backwards. It is highly irritating, however, to be continually plugging and unplugging leads from a largely hidden and densely populated rear panel, and the unplugged ones always slip down behind the table and when you crawl under to find them, there's generally a metal phono plug or two to kneel on and... it's generally a tiresome experience.

What's needed is a separate set of eight tape return sockets and eight buttons to go with them. If the buttons make this too expensive, then the last eight line input sockets could be 'break jacks' wired in parallel with tape returns such that when an instrument is plugged in, the tape return is disconnected. In this way instrument leads could be left half plugged-in and the constant in/out/drop/pickup action centering around the tape return leads could be avoided.

Along with the suggested sweepable mid section on the eq, this is the other main addition that would make a huge difference to the usefulness of productive power of this mixer. Though it is not usual to actually need more than four line inputs simultaneously once the initial track is down, it really is a great help if you can leave your drum machine, synths, guitars, bass and effects returns either plugged-up or loosely half plugged in to their line inputs ready for use. Otherwise it's like re-setting up every time. Even if this added another £25 to the price, I feel it would be very well worth it. Of course all 12 mike inputs are always available (except during remix) and lower level line inputs could be connected to them if the input gain was turned down, but the problem here is one of leads — who has enough XLR to jack leads to connect up all their instruments? On the other hand, just a few would improve the situation greatly.

Back on the positive side, they've made a good compromise on the metering front: there's only a single pair of VUs (and they could be a little bit bigger) but there's a rotary knob that allows you to switch between L-R, 1-2, 3-4, 5-6, 7-8 and PFL. This kind of arrangement seems strangely scarce these days although it was being used on WEM Audiomasters in the early Seventies and works really well for home studio work. The combination of the peak LEDs and the VUs keeps you well in touch with what's going on at various stages of the mixer.

There are a couple of headphone sockets on the front of the mixer for the engineer's convenience. One gives you the stereo mix (ie the same as you would hear over the monitors) and the other plugs you into auxiliary send one — the foldback. My headphones have a 600ohm impedance which is studio standard as opposed to the eight or 16ohm standard for hi fi headphones. These outputs have been designed for the latter and thus hadn't really got enough power to drive my cans at any volume. That won't be a problem if you intend to use your normal headphones, but it would be nice to have a more powerful amp to cope with both extremes.

An excellent feature considering the price is that of a routable effects return — you can permanently connect the output of your reverb device to this effects return socket and a set of routing buttons, identical to those on the input channels, allow it to be sent to any of the tracks on the multitrack or to the stereo outputs for remix. The only limitation is that it isn't a stereo return, and so if you have a stereo reverb device you'll have to use a couple of spare channels to return it. Again, this may be something of an inconvenience whilst recording if you need to record stereo reverb, but most of the time you'll probably only need mono until the mixdown stage, in which case you'll have four channels spare for such things.

Other niceties include a stereo input for the mixdown machine so that having done a mix you can quickly listen back to it at the touch of a button. There's also a socket for a talkback mike which, at the touch of another button, will send your instructions to the foldback — unfortunately it doesn't go to tape for track idents, but that's certainly no big deal. There are inserts on all the channels using the standard stereo jack—tip send, ring return and common screen convention.

Conclusion

Overall I'm impressed with the performance of the 12:8:2; it's acceptably quiet and has a good set of facilities. If it had the extra eight tape return sockets and the sweepable mid on the eq, it would be excellent. Even so, it's still a very usable mixer for a singularly low price.

MTR 12:8:2 Mixer RRP: £523

Also featuring gear in this article

Featuring related gear

Publisher: International Musician & Recording World - Cover Publications Ltd, Northern & Shell Ltd.

The current copyright owner/s of this content may differ from the originally published copyright notice.

More details on copyright ownership...

Recording World

Gear in this article:

Mixer > MTR > 12:8:2 Mark II

Review by Jim Betteridge

Help Support The Things You Love

mu:zines is the result of thousands of hours of effort, and will require many thousands more going forward to reach our goals of getting all this content online.

If you value this resource, you can support this project - it really helps!

Donations for October 2025

Issues donated this month: 0

New issues that have been donated or scanned for us this month.

Funds donated this month: £0.00

All donations and support are gratefully appreciated - thank you.

Magazines Needed - Can You Help?

Do you have any of these magazine issues?

If so, and you can donate, lend or scan them to help complete our archive, please get in touch via the Contribute page - thanks!