Magazine Archive

Home -> Magazines -> Issues -> Articles in this issue -> View

The Emulator... Two | |

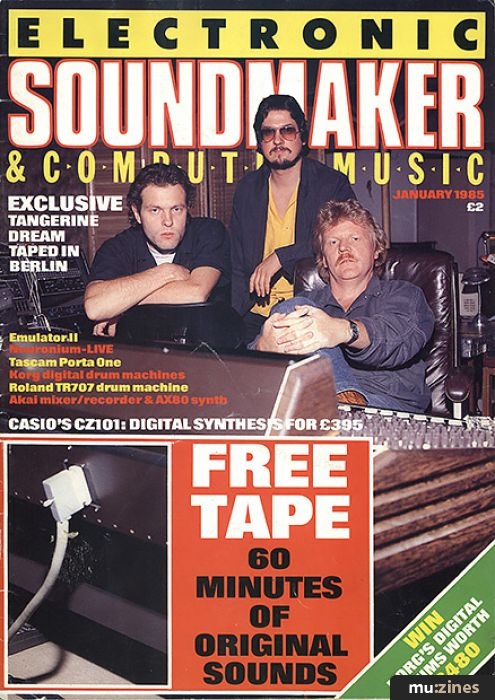

Article from Electronic Soundmaker & Computer Music, January 1985 | |

The original Emulator brought sound-sampling out of the labs and onto the stage. The new model looks likely to repeat that success, and to transform sound sampling from precision recording into something like art.

You thrilled to the earthshaking potential of the original Emulator. Now, stand aside as the new, improved Emulator II gets ready to sweep the High-spec sound-sampling stakes. Curtis Schwartz reports.

Sam'pler (sah-)n. piece of embroidery worked to show proficiency...

Well how's about that then! The lads in Oxford are living in the Victorian epoque. Well I suppose I am being a little unreasonable, as the above definition would have been accurate up until six years ago when the Aussies put the proverbial spanner in the works with their Fairlight computer keyboard.

The result of this uncharacteristically crude behaviour on their part was to take from the poor (session musicians), and give to the rich (successful record producers).

18 months after the Fairlight shook the music business by the balls, out popped a product from California called the Emulator, less than a third of the price of the Fairlight, yet which took the sampling specifications of the Fairlight and put them in an economic package (yet without the extensive sequencing/modification software/hardware etc. that still places the Fairlight in a class of its own).

Emu II

Dave Rossum is the man to thank for this and all other EMU creations - the Emulator I, the Drumulator (one of the most ingenious pieces of software design ever written), and now this equally revolutionary instrument - the Emulator II. Under normal circumstances, this machine would have been called the Emulator VI or VII, due to the staggering level of advancement over its predecessor's design; however, what others do in ten steps, the Almighty Dave Rossum does in one leap. A brief list of improvements on the original Emulator design will undoubtedly confirm this to any cynics of my enthusiasm:

- Sampling times had been increased from two seconds up to 17 seconds;

- Sampling bandwidth has been increased from 8kHz up to 12kHz;

- The filter section has grown from the EI's simple low-pass 'brilliance' control to having a full complement of filters, VCA's, envelope generators and independant delayed LFO's, which are all programmable on each of the eight channels;

- One megabyte of disk-based sound storage, twice what was available on the E1.

- A touch sensitive keyboard, over which any number of samples can be assigned, as long as the 17 second sampling capacity is not overshot (previously the E1 could only play two samples at once)...

These are but a few things that EMU have done with the EII, however to be able to delve deeper into the bowels of this instrument the distinction between voices and presets must be firmly grasped.

A 'voice' is a sampled sound with its initial parameters set using the VCA filter. This is stored on a library disk from where it can be recalled. A 'bank' of these voices can then be loaded from disk into the EII's memory, as many voices as are needed for a particular task (perhaps eleven individual samples/voices of a grand piano over the keyboard, or three string voices and a couple of brass voices for instant recall during a live set). Then within that bank, up to 99 different presets can be made, consisting of perhaps a bass voice over the bottom octave, a Rhodes over the rest of the keyboard, with a few string voices that only appear when the keys are struck below a certain velocity. As long as the various samples do not cumulatively use more than the 17 seconds of sampling memory, then such a preset is possible.

The swift-of-mind among you may, however, have added the decay times of this last example, and come to the conclusion that it would be impossible within the confines of 17 seconds, in which case you will not have taken into account the phenomenon called 'looping'.

Looping on the EII is infinitely more versatile than on the EI, where looping consisted of a direct edit of the end of a sample onto its beginning - resulting in a click. The EII gets round this by using a 'cross-fade' technique, along with a multitude of other controls to help make the loop as inconspicuous as possible: coarse and fine edit point controls, Autolooping, Back and Forth looping, Splicing between voices (a violin turning into a flute for example), Autosplicing...

Boxes Inside Boxes

The EII's front panel layout is organised into seven multifunction boxes labelled Master Control, Sequencer, Enter, Real Time Control, Sample, a dual multifunction box marked Special and Disk, and a multi-multi-function box for Filter, VCA/LFO, Voice Definition, and Preset Definition. (Bottom left there is a box for the not-so-bright marked 'Wheels' in which are two performance wheels, the left one marked 'Left Wheel' and the right one marked 'Right Wheel'!).

Starting with the master control box, this contains controls for Tuning, Transposing, Master Volume, Dynamic Allocation (making all channels available to all voices), four sliders and a keypad. The sliders adjust parameters in some of the menu functions, and the keypad chooses menu functions, enters data and selects presets from a bank when no modules are activated. In the Master Control box is a 32 character LCD display which informs the user of the meaning of life. To the right of the Master Control box is a box labelled 'Sequencer'. However, at the time of writing, the software had yet to be implemented into the EII, so I shall swiftly change the subject - an interesting facet of the EII's design is that when new software is written, rather than having to return the EII to the source of purchase, the software is written on each disk, thereby making it dead easy to update or even downdate back to a software level whence a preset was set up.

To the right of the sequencer is the multi-multi-function box for Filter, VCA/LFO, Voice Definition and Preset Definition. When in the filter mode, there are three sections in which can be found 1) Cutoff Frequency, Resonance and Envelope Amount; 2) LFO and Keyboard Amount; and 3) Attack Decay and Sustain and Release. Preceding these parameters are the letters A, B, C or D, relating to the four sliders in the Master Control Section. Thus if you wanted to alter the LFO amount, you would first select the Filter module, press '2' on the keypad and the move slider 'A', according to the LFO amount your heart desires.

The same method is used for all parameter and function editing. Under the VCA/LFO heading are parameters for VCA ADSR, and LFO rate, delay, variation and routing to the VCA.

Coming on to Voice Definition we have the parameters from which looping, velocity routing (to VCA level and attack, VCF cutoff frequency, attack and resonance), and several other specialised functions for individual voice attenuation and tuning, vibrato depth, single note triggering, various looping 'extras', and a mode for playing a sample backwards (as well as reverse loops)!

Further to the right are the 'Preset Definition' controls which are essentially for filing purposes - to and from disk, memory management, MIDI assignment and Crossfade (between two or more voices allocated to the same keys).

Below this are boxes for 'Real Time Control' (for routing control sources to specific destinations - 'performance controls)'); 'Special' (for self testing and new software loading etc.); 'Disk' (further memory management and save/loading data to and from disk); and finally the magic word itself 'Sample'. This sampling box is deceptively simple, and so makes sampling an ultra simple activity.

Sample preparation

To prepare for sampling you select the VU mode, whereby the LCD will transform itself into a peak holding VU meter. Then you adjust the coarse input level with function 3) Gain Set - 0, 20, or 40dB; and then adjust the output level from the mixing desk to the EII's input for peaks just below scale maximum. Then, with function 4) Threshold Set, adjust the level above which the incoming signal will trigger the sampling. Following that you select 'Define Voice' and choose the range and point at which the sample will sound on the keyboard.

Set the Sample length and finally 'Arm Sampling' and the EII will be ready to capture whatever it hears above the threshold level. I have probably given the impression that this is a longwinded process, however this is not the case, as in experienced hands the EII takes no more than 20 seconds to arm, and less if the default values for 'Define Voice' and 'Sample Length', are opted for, with sampling being activated manually from the 'Force Sampling' switch, and stopped manually with the 'Stop Sampling' switch.

Once a sample is taken, it is not automatically stored into memory, as this is only done once the Enter button is depressed. This is very useful as it enables you to keep on sampling until just the right sample is made, at which point the display will read 'Sample Is Good', and you can then store the sampled voice.

Then, with the sample, you can loop it, crossfade it in or out of another sample, filter it, assign touch sensitivity to up to five different elements of the sound, truncate it, splice it, eat it...

Construction

The EII is characteristically EMU - its casting being a single moulded shell, lightweight yet it looks as though it could withstand a crash cymbal and stand plummeting off the drum riser and onto the unsuspecting EII's front panel - however, I was not allowed to perform this simple test of strength on it unfortunately.

The keyboard, although unweighted, has a light, springy feel to it which my fingers found most pleasing, equally suitable for 'bouncing' ragtime digits, or soft, sensuous stringy digits.

Conclusion

EMU have always been the kind of company who are ten steps ahead of the 'Only Ifs' of this world, and as such, they make the job of the reviewer a little awkward (unless you wish for criticism for criticism's sake).

The EII is undoubtedly a spectacular instrument, possibly being all things to all people. After only a short time with it, my thoughts had drifted from critical analysis, and more into the realms of 'Where can I get eight grand from', and 'I wonder if anyone would notice if I snuck out the backdoor with it under my arm?'

Also featuring gear in this article

Featuring related gear

E-mu Systems Emulator

(EMM Jun 82)

First Born - E-mu Emulator

(MT Feb 91)

Hear You 'Lator - Sampling The Emulator

(12T Dec 83)

Sampling Synths

(ES Oct 83)

Screen Test - Sound Designer Software

(EMM Dec 85)

Sweetening the pill - Sampler test

(MX Dec 94)

Synth Computers

(12T Nov 82)

Browse category: Sampler > Emu Systems

Browse category: Software: Sample Editor > Digidesign

Publisher: Electronic Soundmaker & Computer Music - Cover Publications Ltd, Northern & Shell Ltd.

The current copyright owner/s of this content may differ from the originally published copyright notice.

More details on copyright ownership...

Review by Curtis Schwartz

Help Support The Things You Love

mu:zines is the result of thousands of hours of effort, and will require many thousands more going forward to reach our goals of getting all this content online.

If you value this resource, you can support this project - it really helps!

Donations for April 2024

Issues donated this month: 0

New issues that have been donated or scanned for us this month.

Funds donated this month: £7.00

All donations and support are gratefully appreciated - thank you.

Magazines Needed - Can You Help?

Do you have any of these magazine issues?

If so, and you can donate, lend or scan them to help complete our archive, please get in touch via the Contribute page - thanks!