Magazine Archive

Home -> Magazines -> Issues -> Articles in this issue -> View

Sampling Techniques (Part 3) | |

How To Get The Most From Your SamplerArticle from Sound On Sound, February 1993 | |

The digital mixing of samples can be used to both creative and practical ends — creating new sounds, producing stereo effects, or just saving on sample RAM.

Many samplers, and certainly any sample editing software worth its salt, will have some facility for mixing samples entirely in the digital domain. Now that samples can be matched in pitch through sample rate conversion (see last month's issue) you have no excuse not to experiment with mixing and splicing them together. Sound sources, software, your patience, imagination and the sky are the only limits with creative sample manipulation.

Although everyone's ears are tuned to a different set of values (sounds that attract your ears may make someone else want to stick their fingers down their throat) the techniques are identical whether you're manipulating orchestral instrument or industrial noise samples.

The great thing about digital sample mixing is that the entire process is carried out in software. Without having to go through digital-to-analogue or analogue-to-digital conversions, distortions caused to the audio signal by these and other factors will be avoided, giving you as clean a result as you'll get with modern technology.

Although each sampler or sample editing software package may go about things in different ways there are primarily three things that can be done with such software: mix two samples together, splice one sample after another, cross-fade one sample through another. If you're lucky you'll have all three at your disposal.

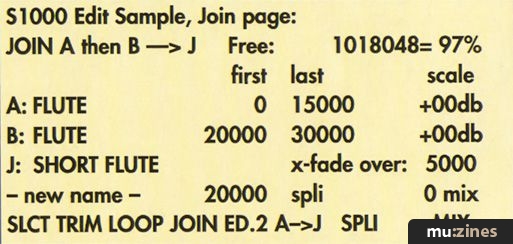

The key to successful sample manipulation is keeping track of where one sample starts and the other leaves off. The only advice I can offer here is to be thoroughly familiar with what sample start and end information your software requires and to keep a pen and piece of paper handy at all times. Here we'll work with the Akai S1000 Sample Join page for the purpose of illustrating dealing with samples in terms of numbers. See if it helps.

DIGITAL MIXING, SPLICING, AND CROSS-FADING

Digital mixing is pretty straightforward. As with splicing and cross-fading you're usually required to specify the start and end points of samples and, may be offered the choice of changing the amplitude of either or both samples in the process.

In this example the new composite sample is 131,708 words (or samples or blocks or whatever the manufacturer calls it) long. Sample 1 is started 643 words into its duration of 132,351 words (132351-643 = 131708), and Sample 2 is 107,775 words long and starting at word 0, is raised in level by 3dB.

Digital splicing is not a lot more involved but, since one sample starts where the other leaves off, matching levels can be extremely tricky.

Here we start Sample 3 on word 0 and end on word 482. Directly after the new sample's word 482 we splice word 318 of Sample 4 and continue until word 15,000, making a new sample length of 15164 words.

Digital cross-fading allows us to fade from one sample to another over as short or long a period as we choose. A short crossfade is usually the answer to spliced samples that give a click at the transition point.

This clears up any problems we might have had with the splicing example. Here we've cross-faded over 164 words and in the process have shortened the new sample length to 15000 words.

You could also try augmenting sounds — add some synth triangle or sine wave to a bass guitar, mixed back so you don't perceive it as a synth sound, to solidify the bottom end of the bass sample or to strengthen the fundamental pitch of an overly breathy flute.

Taking the time to match pitches through sample rate conversion opens up all sorts of possibilities with digital sample mixing. You can create 'bigger' sounds by mixing all your favourite brass stabs or drums together for the ultimate mega-sound. Line up starts if you want a tight composite sample. Experiment with various mixes of the same samples for soft and loud velocity switching sets.

"Delays are easy to construct - simply graft a bit of blank space before the sample start. For a well-defined attack on your delayed sample use a splice, but if you're after a softer attack, for spacey effects for example, go for a cross-fade."

APPLICATIONS: MIXING

There are more prosaic applications for mixing: you can conserve memory by combining as one sample sounds you ordinarily layer on top of one another. (Don't scoff at the work involved. It's not so bad if you work with tape and have multitracking facilities — you can always overdub parts. But if you're a gigging musician and/or have limited facilities, fitting a few more samples into your sampler can mean the difference between realising a great arrangement or not. Either that or buy a second unit. So, if you find yourself layering the same samples in your music try digitally mixing them — it costs nothing but your time.)

I learned the sampling basics years ago on the PPG Waveterm B system, which had the capability of mixing (merging they called it) up to four samples at once. Sadly, with the demise of PPG as a company and with the exception of DigiDesign's Sound Tools and Dynacord's Add 1, all that seems to be commercially available at present is software that allows mixing two samples at once. Saying that, with enough planning you can execute multiple passes, building up a sound in sections and adding them together to give as complex a composite sample as desired.

Building up complex composite samples is not difficult but it does take a bit of planning. Remember, we're working in lots of two samples at a given time, so mixing four samples together involves three individual processes:

SPLICING

Successful splices rely on matching up not only the level of both sounds to be joined but also the wavecycles at which the two samples meet. As with forward loops, it's easier to avoid clicks (glitches) when dealing solely with wavecycles at their zero crossings, either positive or negative. In fact I've spent relatively little time working with simple splices, finding short crossfades to be faster (no levels to match up) and giving highly professional results in practically every case. Excellent splices are possible, but can eat up time with jiggery-pokery like resampling to adjust levels. Rule of thumb — use a short cross-fade if you can, and if you have only splicing software get out the coffee.

The most common application by far is to splice (or cross-fade) the attack portion of one sound onto the body or ambience of another. It all happens so fast with percussive sounds like drums and plucked strings that often the splice needn't be technically perfect. We're talking 10-25 milliseconds or so here, so even if there is a slight glitch it might just enhance the attack of the sound, making it brighter and more pronounced. A harpsichord pluck can be grafted onto an electric piano or the attack transients from a bright snare onto another to give it more bite.

We need not stop there with simple two part splices. Entire series of events can be constructed in the digital domain from a variety of acoustic events and saved as one sample. This comes in really handy with sound effects, eg. 'The Toast': unwrapping champagne bottle foil, followed by a cork pop, followed by pouring and fizz, champagne glasses clinking, and giggles.

Delays are easy to construct — simply graft a bit of blank space before the sample start. For a well-defined attack on your delayed sample use a splice, but if you're after a softer attack, for spacey effects for example, go for a cross-fade. Take the time to record a sample of nothing and save it to disc for future use. For sounds recorded at 44.1 kHz, 1 second = 44,100 samples. When mixed back with the original sample, a spliced delay of 4,410 samples (or 100ms) is a good starting point for 'slapback' echo effects. Delays are very effective panned to one side, the original to the other.

CROSS-FADES

Cross-fades are a lot more creative and give you more leeway than straight-forward splices. The list of what you can do with cross-fades is almost limitless. Here are a few ideas to get your imagination going:

• You can simulate a brass swell by cross-fading a brass section note played forte (loud) through another brass section sample played pianissimo (soft).

"To take sounds from the world around us and mix and match them (in or out of context) to make totally new sounds or sequences of acoustic events is definitely the feather in the cap of the creative samplist."

• Start out with a percussive grand piano sample and cross-fade to a sustained sample like a choir or string section. Also try starting with a bowed string and fading to a grand piano.

• Cross-fade from a thrash metal guitar power chord to ear piercing feedback.

• Cross-fade from one sound to another over several seconds for imperceptible timbre changes, say a clarinet to a sax.

• Cross-fade to a reverse copy of a sample. Or from a reverse version to the forwards version. Great on cymbals. If you spend some time on lining up sample attacks when using a sequencer, some very strange reverse tape effects can be obtained with all sorts of musical, and non-musical, sounds. The 60s strike back!

You can also condense samples — a long sustained sample can often be condensed to cut down on memory requirements or to get rid of an unwanted (or un-needed) centre section. A good example of this is a flute sample that starts out fine, wavers in pitch for a short while then ends up on a nice loop. In this example we're cutting out the portion between samples 15,000 and 20,000, and crossfading the remaining start and end sections into one another over 5,000 samples.

You can also use cross-fading to make the attack portion of a sound more pronounced, by cross-fading the attack back into the same sample at a louder level:

Stereo cross-pans are a lot of fun, and are one of the most theatrical ways of showing off the stereo capabilities of your sampler. For a simple stereo cross-pan you'll need two mono samples, say a trombone and a saxophone. Cross-fade the saxophone into the trombone and pan the resulting sample hard left, and then pan hard right the result of cross-fading the trombone into the saxophone. The effect is that of the instruments sweeping to the opposite sides of the stereo soundfield as their notes progress, the speed of which relies upon the length of the cross-fade.

Long cross-fades on long samples (two seconds, preferably four or more) can give you subtle yet constantly shifting spatial and timbre changes — useful for New Age and atmospheric settings. Short, tight crossfades, on the other hand, will make the samples appear to 'jump' from side to side and sounds great on punchy 'pop' brass ensembles and 'stabs' of all kinds.

FADE AWAY

We'll leave you this month with a technique that is useful when a sample needs to be faded and no external editing software (or computer) is at your disposal. This is really handy, and I use it all the time on the S1000 when trimming percussive sounds, giving a very polished result. The fade appears to be linear; for smooth fadeouts use lengthy fade times, shorter fades for more gated effects. Different fade curves can be simulated by making multiple editing passes and moving the fade points each pass (see right and below).

To take sounds from the world around us and mix and match them (in or out of context) to make totally new sounds or sequences of acoustic events is definitely the feather in the cap of the creative samplist. With the freedom to combine synthetic and natural sound sources, never before have we had such a palate of sounds at our disposal. Get out there and start exploring, experimenting and creating with sampled sound... there are entire universes yet to be discovered.

'Till next month, when we look at ways of getting around adjusting the pitch of samples and mixing them together when you don't have the appropriate software and thought you couldn't, happy sampling.

Series - "Sampling Techniques"

Read the next part in this series:

Sampling Techniques (Part 4)

(SOS Mar 93)

All parts in this series:

More with this topic

Hands On - Emu Emax II |

Sampling Keyboards |

Retro-Sampling - Sampling Classic Electro Sounds |

Criminal Record? - Sample CDs (Part 1) |

An Emulator for £10 |

Making the Most of your Akai S1000 Sampler (Part 1) |

Hands On: Akai S1000 Sampler |

What It All Means - Sampling |

Digital Mixing Magic - With Sampling Keyboards |

Making The Most Of Your Mirage (Part 1) |

The Complete Sampler Buyers' Guide |

A Vocal Chord (Part 1) |

Browse by Topic:

Sampling

Publisher: Sound On Sound - SOS Publications Ltd.

The contents of this magazine are re-published here with the kind permission of SOS Publications Ltd.

The current copyright owner/s of this content may differ from the originally published copyright notice.

More details on copyright ownership...

Feature by Tom McLaughlin

Previous article in this issue:

Next article in this issue:

Help Support The Things You Love

mu:zines is the result of thousands of hours of effort, and will require many thousands more going forward to reach our goals of getting all this content online.

If you value this resource, you can support this project - it really helps!

Donations for April 2024

Issues donated this month: 0

New issues that have been donated or scanned for us this month.

Funds donated this month: £7.00

All donations and support are gratefully appreciated - thank you.

Magazines Needed - Can You Help?

Do you have any of these magazine issues?

If so, and you can donate, lend or scan them to help complete our archive, please get in touch via the Contribute page - thanks!