Magazine Archive

Home -> Magazines -> Issues -> Articles in this issue -> View

Totally Wired | |

Leads & WiresArticle from Making Music, July 1987 | |

Find out about the rubber on the outside, the wire on the inside, the music goes round and round...

Ever felt all caught up in miles of tangled leads? Ben Duncan unravels all the cable you're likely to need, identifying the types of mains, instrument and speaker leads on the market and explaining why some are better than others.

AN IRONY: although we don't need any wires to transmit music over hundreds of miles, we do need wires by the handful to make it all happen in the first place. For like everyone else, musicians continue to depend upon lengths of copper to connect their equipment together.

Paying attention to wires and cables is important once in a while, since they're basically bits of fragile metal and plastic, and as a musician you shouldn't have any trouble recalling broken leads by the handful. Aren't they the most frequent cause of failure and frustration?

Copper is an everyday conductor of electricity. An individual conductor is always covered in an insulator, usually PVC or rubber. Because electricity needs to run in a circuit (what goes out has to come back again), there are always at least two conductors in a circuit. And whenever two or more conductors are joined together, or live in the same jacket or sheath, it's called a cable.

POWER CABLES supply vital juices to the majority of equipment which isn't running on batteries. Commonly, these carry 240 volts (or 230 or 115v), and must be safe and sturdy with a thick, overall insulating sheath as double protection against electrocution. Sometimes, there's an intermediate power supply unit, converting AC mains to low voltage DC. Cables carrying (say) nine or 12 volts DC to, say, FX units can be thinner and may lack an overall sheath. This is safe enough, but certainly less sturdy: if a skimpy cable gets trapped in a door, it's more likely to be wrecked.

SIGNAL CABLES carry musical information. The signals may be analogue or digital, but either way they may be subject to corruption and interference from the magnetic and electrical fields radiated from surrounding equipment and cables. In the everyday analogue connection between a guitar and its amplifier, interference is heard as hums, buzzes or clicks.

In digital interconnections, the interference won't be heard directly. Instead it comes across as a spurious malfunction: a command you programmed gets missed out, or maybe one turns up that you don't remember programming. To prevent this, most signal cables are shielded: one conductor, called the shield or screen, is arranged to surround the other conductors, protecting them from nefarious outside influences.

SPEAKER LEADS carry high currents and moderate voltages. Compared with miniscule currents and voltages running around a typical mixer or guitar circuit, it's a fair bet that five amps and 30 volts pulsing down the average speaker lead won't be so readily messed with.

INS AND OUTS

Many signal cables come to grief because they're too skimpy and delicate for the job. Unlike mains cables, there's no overriding need for chunky conductors (because the current is so low) or fat insulation (because the voltage isn't high enough to be dangerous), and with PVC and copper being expensive raw materials it's tempting for manufacturers to see just how little material they can get away with. Witness the thin grey stuff given away with oriental equipment and sold across the counters of electrical shops. It's fine for the wiring inside equipment, but not up to being twisted, yanked and trodden on. As a general rule, any cable less than 5mm (3/16in) outside diameter (OD) is best skipped over, unless it's going to lead (ha ha) a sedentary life at the back of your recording set-up.

The ability of individual wires to withstand lots of flexing without dying of metal fatigue is down to the thickness of the strands. Thin strands are the most pliable, but we need a group of them to build up strength. A single strand of very thick copper would resist a lot of pulling and tugging, but soon splits when bent back and forth. Take a close look at a few cable ends, and notice the different number of strands in the wires, and their diameter. In cable speak, wires are described with a pair of figures: 1/0.5 means one strand of wire 0.5mm in diameter. This would be useless as a flex, but cool for permanent wiring. '16/0.2' spells 16 strands, each 0.2mm across, and as such it's a classic recipe for rock 'n' roll stage leads. Meanwhile, a top quality studio patchbay lead built to withstand continuous tight flexing might be 128/0.05: that's 128 strands of very fine wire.

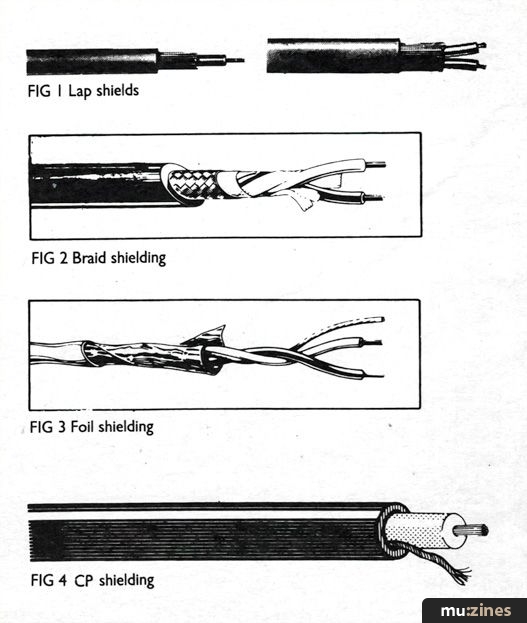

FIG 1 Lap shields

FIG 2 Braid shielding

FIG 3 Foil shielding

FIG 4 CP shielding

Shielding comes in four varieties, and largely determines the qualities of a signal lead.

LAP shielding is the cheapest (fig 1), comprising parallel strands of copper wrapped around in a light spiral. The effectiveness of a shield depends, as you might expect, on how well it hides the centre conductors). The snag with lap shielding is that it soon develops holes when twisted and flexed. Misused as a mike or guitar lead, it rapidly loses its effectiveness, and all hum breaks loose.

BRAID shields (fig 2) are again strands of copper, but this time, they've been woven like cotton, so they'll stay in place and survive much bending and twisting. With top quality cables, the braid is hermetic — meaning it's so densely woven that the inner core's insulation isn't visible. This uses a lot of copper, so it's expensive. With copper being a dense metal, cables with a cheap and thin weave weigh noticeably less. In fact, the shielding can be almost as good with a more loosely woven braid (one we can see through), so it's tempting to cut corners — but loosely woven braids are less good at staying in one piece, and like lap shields, they tend to loose their effectiveness with heavy use.

Summing up, strip back the outer jacket and take a look: for stage leads, it's good to steer clear of cables where the inner core's insulation can be clearly seen through the braid. If in doubt, screw the cable about, to check whether the braid develops big gaps.

FOIL shields (fig 3) are aluminium ('tin') foil. Soldering bits of baco-foil to plugs at either end wouldn't be popular, so the makers wrap the stuff around a length of bare copper wire, called the drain (because it drains away interference, like a gutter). This is the bit we solder to. The foil makes a good, hermetic shield, but is easily broken and torn by kinking and other abuses. On the other hand, it's quick and easy to strip and wire up, making it a favourite for big and tedious wiring jobs, like patch bays. Overall, it's dodgy for PA and backline connections, but ideal for recording set-ups.

CONDUCTIVE PLASTIC (CP) shields (fig 4) are similar in construction: the sensitive inner conductors are wrapped in a special black plastic that's good at conducting away nasty electrical interference, again wrapped around a bare copper drain to make termination easy at either end. But the plastic shield is much more rugged, comparable to the best braid. Cables with CP shielding also tend to stay where you put them, and don't curl up or kink. From the outside, they're readily identified by their surprisingly lightweight and carefree flexibility. They're a firm favourite for stage mike leads. Typical brand names include Musiflex, Rockflex and Phonoflex.

SIGNAL LEADS: WHAT WHERE?

For the home studio and control room, where lead lengths are short and things don't get moved about much, any of the cables described above are cool.

The exceptions relate to connecting signals from high impedance sources, namely guitar pickups, Fender Rhodes, some acoustic pickups, 'Hi-Z' dynamic mikes and cassette recorder DIN sockets. Here, a low capacitance cable should be sought, something with less than 150pF/m (picoFarads per metre). Foil shielding can be microphonic when driven from a high impedance, meaning it can add odd 'rustling' sounds if jiggled about.

If there's a problem with hum pickup with these sources, try rerouting the cable well away from mains leads and the sound equipment. If the buzzing recedes — or at least, changes — then your cable's screening is probably defective. When replacing, avoid lap-shielded cables. Overall, this leaves Braid and CP cables as the universal favourites. Of these, a good conductive-plastic cable is likely to come cheaper.

For on-the-road use, and the studio floor, cables with braid or CP shields are the biz. To survive any length of time, a good sheath is all important. Again, rubber is the most popular material. Unlike PVC and similar plastics, it survives being bitten, trapped under a ton of PA cabinets, run over by grand pianos, and doesn't melt when campfires are built over it.

The one snag is the extra expense. As a result, one of the most crippling purchases a band make for their PA, the multicore (snake), is often an economy model clad in a PVC jacket — and easily punctured. Also for reasons of economy, many multicores have foil shields.

Overall, the multicore is the most delicate cable in the average PA set-up, and should get treated accordingly. Religious roadies uncurl the snake slowly, never allow knots or kinks to develop, and never tug it willy nilly over rough surfaces. If it crosses a public area, you'll find it protected by duck-boards, or (more ad lib) cardboard gaffered over it.

SPEAKER LEADS

Loudspeakers over 100 watts draw very high peak currents, particularly at bass frequencies and whenever a PA is thrashed hard. Power equals volts times amps. Eight and 15 ohm speakers derive their power from high voltages, and pull the least current, whereas 2 ohm units à la Bose pull the highest currents, and need the biggest conductors to avoid power loss.

If the conductors in the speaker lead aren't hefty enough, we can lose a great deal of body from the bass sound, and upset the balance of the other frequencies. At the same time, even a comparatively chunky cable can be too thin if its length is excessive. That's because the problem is one of resistance, equal to length times diameter.

Overall, it makes sense to put your power amps as close as possible to the speakers, ideally no more than six feet (2m) away. It's better to have long signal cables, if this cuts the length of the speaker leads.

Because we don't need any shielding, but we do need a rugged overall sheath, it's common to use mains flex for speaker connections. Sometimes this can be obtained with just two cores, as used for lawnmowers. Otherwise it's three-core and the unused core (earth) gets chopped off to avoid any confusion. Instead of designating the number of strands and their size, cables in this class are usually identified by their cross sectional area, in mm2 (square millimetres). For mains power only, this relates directly to the capacity to carry current, and though it has no significance for loudspeaker duties I've included some current ratings in brackets as a point of reference when you go shopping.

In a home studio where the amplifier can be within a metre (3ft) of the monitors, we can get by with a skimpy cable (eg 0.5mm2), or even a length of old lighting flex. But if the cable is longer than two metres (6ft), or the conditions more arduous, it's best to use the heftiest cable you can lay your hands on — as long as it fits the plugs at either end. With most jack plugs, you can just fit 0.75mm2 (six amp) cable. With XLR plugs and bin-ding-post terminals, 1mm2 (10 amp), 1.5mm2 (13 amp), or even 2.5mm2 (20 amp) cables can be squeezed into place.

CARING FOR LEADS

The gigging life is less hassle if leads and plugs stay in one piece. Leads like to be stored in a neat circular or oval coil. Avoid tying knots. So long as the plugs at either end are carefully tucked in, they should stay free from tangling when you come to use them again.

XLR leads are the most tangle free, since we can plug the male and female ends together so there's nothing hanging loose. If you need to hold the coil together, use string, 'Tywraps' or gaffer.

Cables with PVC jackets develop a 'memory', according to how they've been stored in the past. If they've developed bad knots and kinks or have been coiled into too small a radius, they may resist being tidied into a bigger, neater coil. If this happens, put the cable in a warm place (like an airing cupboard) for an hour or two. This softens the plastic, helping it to forget past kinks. Naturally, longer and thicker cables prefer a bigger coiling radius.

ROLL YOUR OWN?

If you're good at soldering and 'dressing' (preparing) wires, and can be sure of getting hold of suitable connectors, DIY assembly of leads can save a lot of money, particularly if you're wiring up a complete studio or PA. If you can solder but you're not very confident, you'll know after wiring up the first ten (phew!) whether it's your, er, bag or not. Owning or borrowing a decent pair of automatic wire strippers is a godsend.

Signs of dodgy DIY assembly include cables which are too small to be gripped by the connectors' clamping, and where the cable's innards are visible before it reaches the plug. After building a lead, try to rip the plug off. If it stays in one piece, fair enough.

IS READY-MADE CABLE WORTH IT?

If you meet a tasty looking lead in a shop, take a careful look. If the jacket is rubbery, that's good, and accounts for some of the cost. Ask if you can unscrew the plug, and take a look at the termination. Look for dead neat soldering, with no loose bits of plastic or whiskers of wire.

Since moulded connections can't be inspected, and you can't repair them, steer clear unless the price is low enough to justify throwing the lead away in due course.

Now, is the cable securely and positively clamped? Does it shift if you tug hard? Finally, are the plugs firm, solid and business like? Beware of glittery metal.

More with this topic

Setting Up Shots |

Adding an Independent Tracking Output to the 4780 Sequencer |

First Guitar Faults - Your First Guitar |

Polarity Unveiled |

Roland Drumatix Modifications |

Trigger Converter for the Yamaha SPX-90 |

Modifying The Mu-Tron Bi-Phase - For Control Voltage Interfaces |

Workbench - Modifying The Midiverb |

The Shocking Truth |

Drum Hum |

Improve Your Instrument - Really, really serious and totally brilliant ways to... |

Workbench - Signal Processors — the saga continues |

Browse by Topic:

Maintenance / Repair / Modification

Publisher: Making Music - Track Record Publishing Ltd, Nexus Media Ltd.

The current copyright owner/s of this content may differ from the originally published copyright notice.

More details on copyright ownership...

Feature by Ben Duncan

Help Support The Things You Love

mu:zines is the result of thousands of hours of effort, and will require many thousands more going forward to reach our goals of getting all this content online.

If you value this resource, you can support this project - it really helps!

Donations for November 2025

Issues donated this month: 0

New issues that have been donated or scanned for us this month.

Funds donated this month: £0.00

All donations and support are gratefully appreciated - thank you.

Magazines Needed - Can You Help?

Do you have any of these magazine issues?

If so, and you can donate, lend or scan them to help complete our archive, please get in touch via the Contribute page - thanks!