Magazine Archive

Home -> Magazines -> Issues -> Articles in this issue -> View

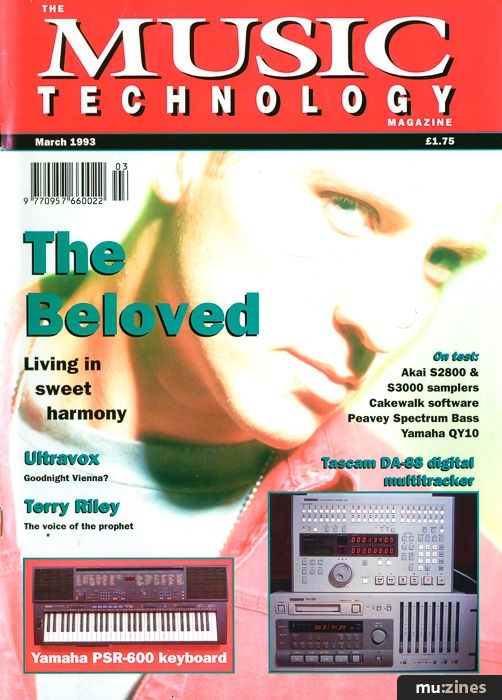

Akai S2800 & S3000 Samplers | |

Article from Music Technology, March 1993 | |

Leaders of the new school?

It's tough at the top, but in the sampling stakes, Akai have every intention of staying ahead of the pack...

Loyalty is the most elusive of human emotions - and certainly one of the most difficult to instill in people. Down the ages, power-crazed despots have lopped off prominent parts of people's bodies in their efforts to encourage loyalty amongst their subjects. Politicians will happily sell their souls to the Devil to win the loyalty of the voting population, while cat owners, anxious to maintain the affection of their brooding pets, must bear the cost of a lifetime's Whiskers and milk.

For Akai it has taken the production of a series of 3U rackmounting samplers and a commitment to continued R&D to win the loyalty of their customers. But win it they have - and now most wouldn't contemplate buying a sampler from any other manufacturer. Of course, when you already produce machines of the calibre of the S950, the S1000 and the S1100, you have something of a problem when it comes to designing new machines which will maintain the loyal customer base you've built up. Things aren't helped either, when you gain a reputation for reliability; what is the incentive for owners of fully functioning S1000s and S1100s to part-ex their machines for a new model? The words 'rod' and 'back' spring to mind here.

But as anyone who read last month's preview will probably know, the incentives most definitely are there and with the release of their two new machines, the S2800 and the S3000, Akai appear poised ready to net a whole new generation of devoted users. In fact, the two machines currently nestling in my rack blow Akai's previous flagship models out of the water. And most of the competition with them...

There are strong family resemblances between the S1000/S1100 and the new units, although the S2800, being physically 'challenged', lacks the pert, angled front panel to hold the buttons and opts instead for a flush S950-type look. The buttons themselves have been radically altered; gone is the familiar sea of white rectangles; in its place a variety of new designs. For example, the major function buttons (Select Prog, Edit Sample, Edit Prog and so on) actually now light up when pressed, rather than relying on an associated LED.

I'm not too sure about the re-designed numeric keypad; I like something substantial in this department to withstand my jabbing fingers, and the new, thinner buttons are perhaps a little too small. But at least they don't rattle. The Cursor Knob from the old-style panels has disappeared too, to be replaced by a 'diamond' of four direction buttons - a la DD1000. They take some getting used to, but overall they represent a significant improvement.

In general terms, it appears that Akai have been paying a great deal of attention to sorting out all the little niggles that came to light on the last generation of machines and have made the S2800/S3000 ergonomically and aesthetically even more appealing. Until you discover their first glaring (and unforgivable) error, that is.

Question: where should the sample input jacks be on a rack-mounting sampler? Answer: on the front panel, where they are easily accessible for the wide variety of input sources from which samples may be drawn. I wouldn't mind but this was obviously realised on the S1000 and S1100; why on earth take such a retrogressive step on two new machines? Very puzzling.

One other area of concern (though I'll admit this is a personal grievance of mine) is the fitting of SCSI ports only as optional extras. On samplers with the potential of the 2800 and 3000, the demand for floppy disks for day to day use becomes unrealistically high. In these circumstances, the provision for a hard disk is virtually essential and should, in my opinion, be included as standard. OK, it would put up the overall price of machines, but the volume costs would surely be lower. You'll almost certainly have to buy a hard disk at some stage and to have your machine adapted to make this possible seems crazy to me.

A range of other, minor features have been added to the exterior of the unit which undeniably make it more user friendly. For example, the headphone output is now on the front panel - thank god! - and an on/off switch for the LCD has been built into the contrast knob, helping to save the little blue lives of displays everywhere. But enough of these trivialities - let's get some noise going...

For the uninitiated, creating a new sample involves the selecting of an existing sample, renaming it and copying it - so that you can then record over the renamed sample to create a new one, leaving the original intact. Having told the unit how long you want to record for and at what bandwidth (20 or 10kHz), it's simply a matter of setting a suitable recording level using the appropriate front panel knob and pressing 'Arm'. When the unit hears the start of the sound, it begins recording, and stops when the allotted time elapses (that's the most common method anyway).

Having obtained your initial sample, you can then go on to edit it - and it's at this stage the new units start revealing some of the tricks Akai have installed up their sleeves. Samples are displayed as waveforms on screen - which may seem a little disconcerting for the unfamiliar, but is actually a deceptively clever way of working. On the S2800/S3000, these waveforms are now plotted as complete bargraphs; the S1000's miserable scribble of a line marking just the top of the plotted points is now a thing of the past.

Naturally, you can vary the Start and End points of samples, truncate them, loop them, crossfade sections, join samples together, timestretch them and resample them at a different bandwidth - all things S1000 users are pretty well accustomed to. These functions are performed through the 'Edit 1' and 'Edit 2' pages - it's 'Edit 3' that holds the real innovations. In this mode various functions have been added which are reminiscent of Akai's DD1000 direct-to-disk recorder/editing system. Indeed, the new S-Series samplers offer you features previously only associated with ludicrously expensive digital editing systems.

The first batch of functions let you edit individual sections of a sample; for example, you could remove a cough from the middle of a vocal sample. The screen presents you with three options for doing this: Chop, which removes the area of sample you highlight between the 'start' and 'end' markers and closes the gap this creates; Cut, which removes the selected area but retains the resultant gap; and Extract, which lets you 'lift' the highlighted area out of the sample altogether and remove the remainder of the waveform. One obvious application lies in the editing of drum loops; now you can isolate a single snare sound from a sample, or remove the kick drum to create a second version of the loop. Think how easy that makes customising, and individualising loops taken from sample CDs.

Another new feature is a facility which makes it possible to normalise or rescale the gain of a sample. This is something many S1000 users would have killed for. Basically, if you have under-recorded the original signal, pressing 'normalise' expands the entire waveform to fill the available headroom, bringing the volume of the sample up to the optimum operating level.

As you might imagine, this can make a world of difference to flaccid bass and drum sounds, and is particularly useful when it comes to multisampling an instrument across a whole keyboard, serving to keep the volume of the sound uniform. Rescale is a more drastic affair, in which the user chooses a level in dB for the entire sample to be cut or boosted by. Executing this causes the loudest point in the waveform to increase/decrease by the set amount, with the rest of the sample increasing/decreasing proportionately. It's a rough way of tweaking the volume of the sample, but again, very effective - providing you don't drive the signal into clipping, which it's all too easy to do.

Finally, Akai have added a 'fade' facility by which you can set up a digital fade-in or fade-out on a sample. Again, blindingly simple, this function will see a great deal of use when it comes to smoothing off the sharp start and end points of a string or pad sound.

Admittedly, these inclusions might not seem particularly earth-shattering to the casual passer-by, but for those who spend many hours of their lives gazing into electric-blue LCD screens trying to manipulate samples in ways their machines will not allow, Akai have suddenly become A Very Special Company once more.

But the carnival doesn't stop there, as the Edit Program mode goes on to reveal. It's on these pages that you take your samples, assign them to areas of the keyboard, set up MIDI and performance data and basically turn the unit into a multitimbral sound module. As you might imagine, you are presented with all the data necessary to do this - again, the system is S1000-derived - but rather than simply restricting these to key ranges, MIDI channel numbers, pan settings and so on, Akai play their trump card with the addition of a new filter section. Not only this, but filters which can be controlled in real time. Hold me back...

A major new element in the design of the S2800 and S3000 takes the form of Assignable Program Modulation (APM), a feature which lets you route virtually any MIDI controller to almost any 'module' in the sampler - a module being the filter section, amp section, pitch, LFOs, envelope generators and so on. Those of you familiar with old synths will instantly realise what this means: you could, for example, route the modwheel of your keyboard to open a filter while you're playing a sound (to recreate the character of a bubbling analogue synth). You could use the second envelope to control the pitch, for more off-the-wall, effects and you could try controlling the LFO from your keyboard to add vibrato or 'rotary speaker' effects to organ sounds. You could also... no, sorry, I'm getting carried away...

I've already mentioned the basics of program construction and getting your samples into 'performance' mode is extremely simple - so I'll not detail every single parameter which can be controlled using APM. Naturally, the filters are the feature most people will get worked up about, so let's go straight to these.

The S2800 and S3000 are equipped with 12dB/octave low-pass resonant filters which make it possible to alter the tonal character of your sample (using variable cutoff, velocity and resonance) from within the machines themselves. Other options allow you to use the modwheel, pitchbend, LFO1, Envelope1 or an external controller to open or close the filter.

Bearing in mind that you can shape the waveform of your sample using the twin envelope generators (the second of which is a multistage envelope), and then use LFO at various stages, what we're really talking about here is the 'front panel' of an analogue synth included within each of the new machines. And lo! - Akai have actually included a diagram of this 'panel' in the manual.

To sum up, the new S-series samplers actually redefine the concept of getting creative with samples in a way not previously imagined on machines of this kind. I found I was able to bring incredible life to string parts (in real time), add an extra rasp to brass instruments, and much greater depth to bass.

Which brings me to another area of improvement - dynamic range. It's generally recognised that, good as it was, the S1000 lacked something in terms of bottom-end, particularly when it came to dance or pop music sounds. This, to make a massive understatement, is no longer a problem. I don't know what Akai have done to extend the range of the S2800 and S3000, but both units are capable of producing unbelievable bass and clear, sparkling highs. The problem is, trying to describe how this (and the filters) have transformed the sound is all but impossible on the page - you just have to hear it. Once you do, it's going to tear apart your ideas of how any piece of digital sound generation equipment should perform. Add to that 32 voice polyphony, APM and the countless improvements that have been made to the operating system and editing facilities, and you have machines that will once again set the standard all over the world.

It's hard not to admire Akai; the enormity of the task of improving machines like the S1000 and S1100 could well have been their undoing. That they have succeeded can only be due to the fact that they have been prepared to listen to what musicians had to say about samplers and what they would like to see included on the new machines. Myself, I'm preparing for severe withdrawal symptoms when the S2800 and S3000 leave my studio. My loyalty to Akai has started to take root and I'm not even an owner.

Background

Vive le difference

But there are greater variants; the 2800 only has two individually assignable outputs compared to the 3000's three; it offers less in the way of memory expansion potential (a maximum 16Mb compared to the 3000's 32Mb) and no SMPTE interface option. Although this might not seem like much, it cuts heavily into the cost of manufacturing, making the 2800 a not insignificant £800 cheaper than its big brother, and thus within easier reach of the amateur/semi-pro.

Other than that, you get the same 16-bit quality with 20-bit internal processing, the same 64x oversampling, the same advanced editing, the same 32-voice polyphony (phew!) and the same real pleasure using both units.

The Spec

Shared

Sampling resolution: stereo 16-bit linear with 64x oversampling

Sampling rates: 44.1kHz, 22.05kHz

Internal processing: 28-bit D/A conversion: 20-bit with 8x oversampling (L/R); 18-bit with 8x oversampling (individual outs; each one has its own DAC)

Polyphony: 32 voice

Default sample RAM: 2Mb

Maximum number of samples: 255

Maximum number of programs: 254

Filtering: Low-pass, -12db/oct with resonance

Envelope generators: 2

LFOs: 2

Effects: echo, chorus, pitchshift and delay

Assignable independent audio outputs: ¼" phono jack (unbalanced) x 2

Connections: stereo headphones jack, footswitch jack, MIDI In, Out & Thru.

Display: 40 characters x 8 lines (text), 240 x 640 dots (graphics); backlit

S2800

Maximum sample RAM: 16Mb

Standard audio inputs: ¼" phono (balanced) x 2

Standard audio outputs: ¼" phono (unbalanced) x 2

Interface boards: SCSI and AES/EBU digital I/O, both optional

Onboard storage: 3.5" DSHD/DSDD floppy drive

Casing: 2U 19"

Weight: 7.7kg

S3000

Sampling resolution: stereo 16-bit linear (internal digital signal path from CD-ROM unit)

Maximum sample RAM: 32Mb

Standard audio inputs: XLR (balanced) x 2, - ¼" phono (balanced) x 2

Standard audio outputs: XLR (balanced) x 2, ¼" phono (unbalanced) x 2

Interface boards: SCSI fitted as standard

Onboard storage: 3.5" DSHD/DSDD floppy drive, optional 105Mb hard drive

Casing: 3U 19"

Weight: 9.7kg

Also featuring gear in this article

Featuring related gear

Akai CD3000 - CD-ROM sample player

(MT Sep 93)

Akai CD3000 - CD-ROM Sample Player

(SOS Sep 93)

Browse category: Sampler (Playback Only) > Akai

Publisher: Music Technology - Music Maker Publications (UK), Future Publishing.

The current copyright owner/s of this content may differ from the originally published copyright notice.

More details on copyright ownership...

Review by Ian Masterson

Help Support The Things You Love

mu:zines is the result of thousands of hours of effort, and will require many thousands more going forward to reach our goals of getting all this content online.

If you value this resource, you can support this project - it really helps!

Donations for April 2024

Issues donated this month: 0

New issues that have been donated or scanned for us this month.

Funds donated this month: £7.00

All donations and support are gratefully appreciated - thank you.

Magazines Needed - Can You Help?

Do you have any of these magazine issues?

If so, and you can donate, lend or scan them to help complete our archive, please get in touch via the Contribute page - thanks!