Magazine Archive

Home -> Magazines -> Issues -> Articles in this issue -> View

The Sequencer Bible | |

The MT Software Sequencer Buyer's BibleArticle from Music Technology, October 1992 | |

The only guide you'll ever need

Which sequencer should I buy?

With over 60 sequencers available across the four main computers, how do you decide which will do the job for you? The following questions should give you an idea of the sort of things you need to ask yourself before Buying...

HOW EASY IS IT TO USE?

As in most walks of life, it's usually easier to work with something you're familiar with rather than going through a learning curve for something new. Sequencing programs are a perfect example of this. There tends to be two principle ways in which they work. The first is where each part of a song is encompassed in a pattern - much the same as a drum machine. Such a system can make the composition of a piece of music very easy as a pattern can be created for, say, the first verse and used (perhaps with some minor changes) for ensuing verses as well.

The alternative is to work with linear tracks, rather like you would using a multi-track tape recorder. Each track has a different instrument and by recording a track in, say, four or eight bar phrases, the entire track can be assembled.

Steinberg Cubase on the Macintosh is a good example of a multi-platform sequencer. The well-known version is on the Atari ST.

Many of the current crop of software sequencers utilise both of these techniques. For instance, you might be able to take the parts from all tracks that lie between bars four and twelve, group them together and then use the grouping as a pattern. This lets you record a song in linear track fashion, and then rearrange it by using patterns if you wish.

A second concern has to be the visual elements of the program. For example, given the right software the mouse can be a very powerful tool for drawing curves in order to fade music in and out and pan sound across a stereo image. Visuals are also important when it comes to editing a sequence; it is usually easier to edit a note represented as such on the screen than by searching through lists of numbers or events. Though of course, different people prefer different methods of working.

HOW MANY TRACKS DO I NEED?

Steinberg Cubase on the PC under Windows is a good example of a multi-platform sequencer. The well-known version is on the Atari ST.

You may think that as there are only 16 MIDI channels, there is little point in having more than sixteen sequencer tracks. Such thinking comes from looking at the 'tracks' of a sequencer in the same way as those of a tape recorder. To give an example: if you had a single microphone and wanted to record a drum kit, the sounds for all of the different instruments would have to be recorded onto a single track. However, if you could use eight microphones, each positioned to pick up a particular instrument of the kit, you could record the drums on eight different tracks. This has the advantage of giving you greater scope at the mixing stage.

In a MIDI sequencer set-up, you might use different tracks for the different percussion instruments such as bass drum, snare drum etc, and so require eight or ten tracks just for the drums. Where these sounds are derived from a single source, say a drum machine receiving on MIDI channel 3, all the relevant tracks on the sequencer would be set to channel 3, but each would be sending out individual note-on messages relating to the instrument assigned to it. Thus, the fact that there are only sixteen available MIDI channels does not necessarily impose a restriction over the number of tracks a sequencer may offer.

Dr. T's KCS on the Amiga. This has separate visual editing and scoring modules amongst others.

The advantage of using several tracks in this way becomes clear when you want to change the sound of one percussive instrument. Let's say that you use a drum machine for the percussion sounds but then decide to also make use of a great snare drum you happen to have on a synth. If the MIDI information for all of the drums is recorded on a single track, you may - depending on the facilities of the sequencer - have to go through every note to change the pitch for the snare drum. If the drums are on individual tracks, a simple track transpose will solve the problem.

Another reason for needing more than 16 tracks is that it is often easier to record Pitch Bend and other MIDI performance information on separate tracks from the notes. This lets you edit information much more easily. Let's say that you've set up a fade-out using MIDI Volume and then decide that the fade isn't quite correct. It is easier to view and edit the data for the fade if it is separated from the note information.

Dr. T's KCS on the ST, where it is known as Omega. This has separate visual editing and scoring modules amongst others.

Taking all these extra requirements into account, it is easy to see why some sequencers offer up to 64 separate tracks. There is of course, a possibility that using a large number of these tracks, sixteen MIDI channels really wouldn't be enough. Using a multi-timbral synth or expander with up to eight voices, for example, would drastically reduce the MIDI channel availability if each was set to receive on a different channel.

That's why another point to look for is whether any hardware is available to expand the number of MIDI Outs - especially on Atari ST software. While the Apple Macintosh, PC and Amiga all use separate MIDI interfaces, any expansion of the built-in MIDI ports for the ST requires an add-on.

A spread of Atari ST sequencers. From top left reading across and down; Concerto, Midistudio Master, Sequencer One Plus, Virtuoso, Trackman II, Realtime, EditTrack Gold and Startrack. The ST has proved to be the most popular computer for sequencers due in no small part to the in-built MIDI sockets.

WHAT KIND OF EDITORS DO I NEED?

This depends on the way that you work and your musical background. If you are a trained musician, the chances are that you will want to work with standard notation. If this is the case, check that the sequencer you choose can also print out the score if you need it to and that it supports the printer that you intend to use.

If you are working with drum rhythms, you will probably need an editor which allows for step-time entry so that you can input the drum notes one at a time without using a MIDI keyboard. Many sequencers have a dedicated drum editor which includes a list into which are entered the names of the percussion instruments used, their MIDI note numbers and a user-friendly grid for note entry. (This and other information is, of course, included in our Buyer's Guide.)

The other most common editor is the one that presents you with a 'piano- roll' type display. This usually comprises a vertical keyboard with horizontal notes in the form of rectangles appearing on an adjacent grid - the length of the rectangles representing the length of the notes. It is referred to as a piano-roll editor because in operation it resembles the action of the old player pianos where holes in a paper roll caused to the notes to sound as they moved past the keyboard. In its MIDI sequencer form, this system makes changing the note value, position, length and velocity extremely easy and quite intuitive.

Many sequencers also offer a MIDI event list which catalogues all notes and other MIDI information along with the time at which they occur. Such lists can be useful for changing certain MIDI parameter throughout all entries, but are generally too number-oriented for most people to feel comfortable with.

Most modern synths respond to MIDI performance messages such as Pitch Bend, Aftertouch and the various MIDI Controllers such as Volume, Modulation, Pan and Sustain Pedal. To simplify editing of this information, many sequencers have a special Editor which allows you to draw curves to control the above MIDI information. This is especially useful with MIDI Volume (Controller #7) and Pan (#10) and some sequencers incorporate this within their Graphic Editor.

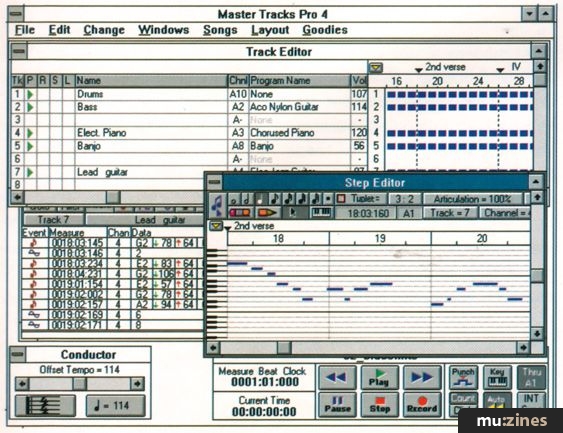

Sequencers using the PC under the Windows environment are becoming more popular. Passport MasterTracks is also available on the Macintosh.

IS THE TIMING GOOD ENOUGH FOR ME?

By their very nature, all computers will subtly alter the timing of MIDI information that they record. The accuracy of timing is usually referred to as the resolution of the sequencer and is measured in pulses per quarter note (ppqn). Most modern sequencers have resolutions of at least 192 ppqn with many offering 240, 384 or 480 ppqn. Generally, the higher the number, the less audible the effect of the timing inaccuracies. However, the relatively slow speed at which MIDI itself works has to be taken into consideration at some stage and it is doubtful if extremely high resolutions offer any real advantage, musically.

Bars & Pipes on the Amiga.

How audible timing variations are also depends on your perception. Tests have shown that some people start to hear delays when they reach around seven milliseconds, while others remain impervious to them. The only meaningful test is to turn off the sequencers's metronome and to record a series of notes. If you can hear any change on playback, then the resolution of the sequencer you are trying is probably too low for you. But it has to be said, the chances of this occurring with present-day programs is pretty slim.

CAN I DUMP MY SYNTH SOUNDS TO THE SEQUENCER?

Cakewalk for Windows is a new entry to the market.

Most synths can dump the information for their sounds via their MIDI Out, and as long as a sequencer can record System Exclusive (SysEx) - the format used for such a dump - it can act as a sound librarian. Sequencers will generally handle SysEx in one of two ways: as standard MIDI data in which case it can be recorded and played back on a normal track, or by using a dedicated SysEx librarian. Either of these can be very useful if you come back to a song some time after first recording it, because they save you the trouble of hunting around for the particular sounds that you originally used.

Notator Logic on the Macintosh, which is about to be released from C-Lab, uses a very visual approach to sequencing.

WHAT HAPPENS IF I MAKE A MISTAKE WHEN I'M EDITING?

Rule number one when editing a sequence is to frequently save to disk! That said, most sequencers have an Undo facility where you can take the sequence back to the situation it was in just before the last edit. To do this, a sequencer has to use some of the computer's memory which reduces the available memory for editing. Some sequencers allow you to turn Undo off which you may need to do if you are carrying out extensive editing. Another common trend is that of non-destructive editing which means that you can always return a track, or part of a track, to its initial state. Useful when you make a total mess and haven't saved...

CAN I SYNCHRONISE MY SEQUENCER AND TAPE RECORDER?

C-Lab Notator on the ST is one of the main programs on their respective computers.

Whether you have a cassette multitracker or a reel-to-reel recorder, the chances are you will want to be able to sync this with your sequencer. This will usually require an extra piece of hardware which can record a special sync signal to tape and read it on replay to make the sequencer play in time with the recording on tape.

The cheaper systems use a method called FSK (Frequency Shift Keying) which encodes timing pulses (MIDI Clock) transmitted from a sequencer into a code that can be recorded to tape. Unfortunately, this means that the code has to be started from the beginning each time so that you can't start a song in the middle and get the sequencer to lock on. Slightly more expensive devices use Smart FSK - smart because special song locators called Song Position Pointers are also encoded and recorded to tape, allowing you to start a song from any position on tape.

Mark Of The Unicorn Performer on the Macintosh is one of the main programs on their respective computers.

A more standard tape code exists in the form of SMPTE which can then be converted to either MIDI Clock, with Song Position Pointers, or to MIDI Time Code - another type of sync which many sequencers can recognise.

A number of manufacturers have developed special sync units to go with their particular sequencers. For instance, most companies who support the Atari ST have their own sync boxes which usually include a number of extra MIDI Ins and Outs along with a time code generator. As the Apple Macintosh has to have a separate MIDI interface, connected to its modem and/or printer serial ports, this interface often incorporates a time code generator and so can be used with any sequencer on that computer.

Ballade (PC-DOS) is dedicated to work with various Roland synths.

The situation with the PC is rather different in that an internal card is normally used which will vary from having a simple MIDI In and Out to incorporating multiple MIDI ports and a time code generator. Check the PC Card boxout for more information.

CAN I USE THE SEQUENCER TO CHANGE PATCHES ON MY SYNTHS?

Most current synths have a number of patches on-board. These are memories which hold the information for a particular sound or group of sounds. With a multi-timbral synth you can usually call up a group of sounds for a song via a single MIDI Program Change which would usually be sent at the start of a song. Alternatively, one sound within a patch can be altered by sending a Program Change on the MIDI channel for that sound. This allows you to change individual sounds in the course of a song. Some budget track-based sequencers will only let you assign a Program Change per track at the beginning of that track - which does not allow you to easily change sounds during the course of a song. Such sequencers are rare, but it is always worth checking that this facility is available if you feel that you need it.

Sequencer Plus Is a popular PC-DOS sequencer.

AUTO CORRECTION

Very few of us can play exactly what we intend. Quantising moves notes to a note position specified by you to try to improve the timing of your playing. For instance, selecting 16ths will move every note onto a 16th beat of the bar. However, this means that if your playing is very loose, it may be impossible to quantise successfully and some notes may have to be moved manually. There are various different kinds of quantising. The most common is where the Note On is moved to the stated quantise value and the note length is kept the same. A possible alternative is to move both the Note On and Note Off to quantise values. This has the effect of also changing the length of the note and can be used to ensure that notes are butted up to one another - that is, 'legato'. A further possibility is to move notes which are more than a certain distance away from the quantise value nearer to the value, but not all the way - 50% perhaps. Notes which are within the certain distance are moved onto the quantise value. This can tighten up a piece of playing without making it feel strictly regimented.

Humanising

This continues on from the point in the section on Quantising, where different techniques are used to ensure that a degree of human feel is left after correcting the timing of notes. Some sequencers allow you to tightly quantise and then move all notes a little before or after their timing values to 'loosen' up the feel. The problem with this is that you can end up losing control over the order in which notes are played - and that doesn't make a piece sound human, just wrong!

TYPES OF RECORDING

Most recording on sequencers is done in real time - in a similar way to a tape recorder. Play a MIDI keyboard and the MIDI information is recorded on the sequencer. Most sequencers have a cycle record mode where you can add extra notes each time the eight bars (or whatever you're working on) cycles round. There are usually facilities to let you delete the last take, if you've made a mistake which would be difficult to correct subsequently or to auto-quantise at the end of a cycle. This is especially useful when you are recording drums, for example, because of the difficulties of recording overdubs when earlier notes are not in time.

There are two further points worth checking, here. Can the sequencer record System Exclusive in real time? If it can, you can record sound parameters for a synth at the start of a song and so ensure that the correct sounds are present when the song starts to play. Secondly, does the sequencer allow you to edit in real time? Can you move between editing screens, quantise, make adjustments to velocities, and so on, while the sequencer continues to play? If not, you will have to stop the sequencer each time you want to make an edit, which will slow you down and can certainly lead to frustrations.

Step-Time Recording

Certain types of recording are better off done in step time - which means that events are placed step by step on a grid of some type. Drum patterns are a typical example of this; it is easier to work out a drum riff as a drawing on paper and then enter it on-screen than to rely on being able to get 'close' by playing notes on a keyboard and editing them to the precise position you require. Steinberg's Cubase comes with a particularly good example of a step-time drum editor.

Notation is often entered in step time for similar reasons; duplicating a score is frequently easier to achieve in this way rather than by real time playing.

ALTERING DATA

Practically all sequencers have this facility. The MIDI data arriving at the MIDI In port is re-transmitted from the MIDI Out on the MIDI channel that you have set for the current sequencer track. This is often referred to as 'Soft Thru' and is an important feature as it stops you from having to continuously alter the MIDI Out channel from your keyboard when you want to access sounds on different synths operating on different MIDI channels.

Filtering

There are many occasions when MIDI data appears at the MIDI In of a sequencer - even though you neither want nor need it. Aftertouch is one of the most common examples (especially when you are attempting to play 16th hi-hats from a note on a keyboard!) Most sequencers have an input filter page which allows you to ensure that certain kinds of MIDI data are ignored and not recorded. This can also save vast amounts of computer memory - as can reducing the amount of continuous data such as Pitch Bend, Aftertouch and some MIDI Controllers once it has been recorded. You can often remove three quarters of such data without any audible result.

MIDI FILES

There are three types of MIDI File, the most common of which is Format 1, multiple linear tracks. (Practically all sequencers will save and load this format.) Format 0 is a single linear track which is used by certain MIDI File playback units (such as Yamaha's MDF2). Most sequencers do not give you the option of saving as Format 0 - if you have more than one track they automatically save in Format 1. To ensure you can save in Format 0, all tracks have to be merged together. Format 2, multiple patterns, is very rarely implemented. Care has to be taken to ensure that parameters which only affect the playback of a sequence are, in fact, part of the data being saved to a MIDI File. For instance, sequencers which always keep the original data but allow you to carry out playback editing such as quantising and velocity adjustment will not usually write such edits to a MIDI File. You often have to go through a procedure sometimes referred to as 'normalising'.

COPYPROTECTION

The hardware key - often referred to as a 'dongle' - usually plugs into the cartridge port on the Atari ST. When a program loads, it checks for the existence of this key and continues to check for its presence every so often. Unfortunately the poor quality of this port's contacts is often to blame for a key being misread and the subsequent crashing of the sequencer.

Where the Apple Macintosh is concerned, the more expensive sequencers tend to use copy protection. Some have an installation procedure where a key file is transferred from the master disk to the hard drive. The disadvantage of this is that a hard drive crash requiring reformatting becomes the kiss of death to such an installation.

Steinberg Cubase and C-Lab Notator Logic are both about to start using a small hardware key with the Macintosh to get around the awkwardness of the key file approach. It will be interesting to see how Mac users react to this, especially in America where the use of hardware protection on the Mac is considered sacrilege!

WHICH COMPUTER?

If your computer is going to be used purely for music, then you have to look for the package which most fits your needs. Think along the lines of: Do I need notation? Do I need to print out a score? Do I want a specifically pattern-based sequencer? And so on, until you've narrowed down the market in which you are looking. Always look at the cost of essential peripherals, too, such as a monitor, hard drive and MIDI interface. What may appear to be a cheap option often ends up more expensive once you add on the various bits and pieces that you need.

Finally, make certain that you have enough RAM (Random Access Memory) for the sequencer of your choice. Many computers can be upgraded by using relatively cheap cards called SIMMs, but again, this adds to the overall cost of your system.

PC MIDI CARDS

There is a difference in the way that MIDI interfaces are handled by DOS and Windows software. A sequencer running under DOS has to provide its own software driver to 'speak' to a particular interface, or have a driver program loaded into memory which provides a standardised interface between DOS and the MIDI card. With Windows, all drivers are part of the Operating System; it now becomes the hardware manufacturer's task to ensure that an existing driver supports their interface. If this is not the case, the MIDI interface will not work. For example, Yamaha has a MIDI interface on their TG100 synth module which Yamaha (US) are currently writing a Windows driver for.

TERMS USED IN THE BUYER'S GUIDE

Resolution: The accuracy of recording timing is usually referred to as the resolution of the sequencer and is measured in pulses per quarter note (ppqn).

Memory requirements: Sequencers will work with the stated "required" memory. The "recommended" memory ensures that facilities will not be limited or song sizes restricted.

Screen requirement: Of importance to the PC, where an internal card may be required, and the ST, which can run in high (mono) and medium resolutions (colour).

Editors: Graphic editors are usually of the "piano roll" style with either a vertical or horizontal on-screen keyboard. A Drum editor usually means one with step-time input but with no interest in the length of the note. Arrangement means that a song can be recorded as a group of phrases and then re-ordered. If a sequencer only offers a copy and paste facility, this does not count as the ability to re-arrange a song.

SysEx Record: If a sequencer can record System Exclusive, it can store sounds and patches from a synth or other MIDI device. This facility will either be in "real time", so that parameter changes can be imbedded within normal MIDI data, or as a "librarian".

MIDI File Read/Write: Most sequencers can import and export songs in MIDI File format. See the relevant boxout for more information on the two different formats generally used.

External Sync: Sequencers will usually recognise MIDI Clock with Song Position Pointers or MIDI Time Code or both. In some cases, a sequencer can only act as a master by transmitting MIDI Clock.

Additional hardware: As the Atari ST has built-in MIDI sockets, some manufacturers make additional MIDI expansion boxes. The number of MIDI sockets and whether a timecode generator (SMPTE) is included is noted.

More from these topics

Machines £1500 to £2500 |

Synthesis on a Budget - The E&MM Buyers' Guide For Beginners |

Software Support - Hints, Tips & News From The World of Music Software |

Software Support - Hints, Tips & News From The World Of Music Software |

The Complete Sampler Buyers' Guide |

Valve Guitar Combos Roundup |

Sequencers Have Feelings Too |

Software Support - Hints, Tips & News From The World Of Music Software |

Ancient Cymbals |

Lab Notes: Blessed are the Seque |

Software Support - Hints, Tips & News From The World Of Music Software |

Drum Modules & Accessories |

Browse by Topic:

Buyer's Guide

Sequencing

Publisher: Music Technology - Music Maker Publications (UK), Future Publishing.

The current copyright owner/s of this content may differ from the originally published copyright notice.

More details on copyright ownership...

Feature by Vic Lennard

Help Support The Things You Love

mu:zines is the result of thousands of hours of effort, and will require many thousands more going forward to reach our goals of getting all this content online.

If you value this resource, you can support this project - it really helps!

Donations for January 2026

Issues donated this month: 0

New issues that have been donated or scanned for us this month.

Funds donated this month: £0.00

All donations and support are gratefully appreciated - thank you.

Magazines Needed - Can You Help?

Do you have any of these magazine issues?

If so, and you can donate, lend or scan them to help complete our archive, please get in touch via the Contribute page - thanks!