Magazine Archive

Home -> Magazines -> Issues -> Articles in this issue -> View

Richard Harvey (Part 1) | |

Richard HarveyArticle from Sound International, January 1979 | |

Meanwhile Richard tells me that Richard is a multi-instrumentalist and used to play with Gryphon. Course I knew that cos I've read the piece, but you haven't yet, have you?

Richard Elen discusses past and present with multi-instrumentalist Richard Harvey; this month we look at the past, and Richard's band, Gryphon... next month we take a look at his forthcoming solo album.

Richard Harvey is a member of a rare breed — the multi-instrumentalist. He started playing recorder when he was four, going on to play percussion and clarinet in the band and orchestra at his grammar school, Tiffin's in Kingston-upon-Thames. At this time, apart from the Beatles, he had no contact with rock music at all, and it wasn't until he studied at the Royal College of Music that he began to meet other people who introduced him to rock'n'roll through such bands as Yes — particularly via The Yes Album. Suddenly he discovered that at least some rock musos 'could actually play'! Richard suddenly realised what he'd been missing.

Among those he met in the corridors of the RCM was one Brian Gulland, who bounded up to him one day and whispered 'Do you smoke dope?'. Thus were friendships formed. He got involved with a circle of people who were interested in rock music, and through this Richard began to change his ambition of playing in one of the big orchestras. He got together with a lute player called Chris Wilson who was playing Renaissance music in a Fulham Road restaurant called Teddy Bears' Picnic, and they played as a duo.

Richard feels today that very many modern classical composers have developed their own rules and stick to them so rigidly that there's no room for creativity. Rock bands, however, have retained the freedom that was created by such composers as Stravinsky. Richard feels that Rite of Spring was a watershed: after that you could do anything you liked. But many composers rejected this new-found freedom and, as a result, will not be remembered. He feels that in the future people will remember the Beatles, Terry Riley, Stockhausen, a few major rock bands; a handful of innovative people, but none of the more pretentious avant-garde composers.

Richard would like to see far more sponsorship of new music, however, along with a more enlightened attitude from the record companies. He'd like to see the companies more willing to release experimental music, more willing to cater for things that are more creative than the average disco single. British radio, he feels, has contributed to a decline in the standards of the British record industry, with its failure to air anything that isn't aimed at the lowest common denominator.

There are people composing and playing today, I suggested, that were combining the best of rock, jazz, avant-garde and whatever, to produce good music, combining with these the immensely powerful mood-evoking techniques of traditional classical composition. He agreed, feeling in addition that a lot of the music never got heard. 'Neglecting traditional techniques,' he suggested, 'is like removing the entire podium on which music stands.' Such a good line, I thought.

Richard feels that the record companies are the new patrons of the arts, yet there are A&R men who'll come up to you and tell you that they won't put a record out unless they're sure it'll get to Number One; and be proud of it. Such are the pressures that the modern creative composers must overcome. He's sad that the days are apparently gone when a musician could do something really interesting on a low budget and release it, to sell 25 000 or so copies. Yet such an album can make money. I thought immediately of some of the musicians who have suffered in this way and have been trying to find ways round the problem, such as those mentioned in our Alternatives to 'Product' section in SI 4. But today's record companies are too blinkered; everything must be a hit. Multi-instrumentalists like Richard may find themselves in difficulties too, with primarily instrumental albums which are — at first sight — not chart material. One thinks here of people like Martin Briley and Mike Oldfield — remember the trouble he had getting a company to take Tubular Bells? But there the egg was on everyone else's fades when the album shot to the top. An object lesson, perhaps, for the companies.

But to return to Richard's past. The Teddy Bears' Picnic group became a trio, with Richard on sopranino recorder and a bit of glockenspiel, Chris on lute and a bit of sitar, and Brian Gulland playing bass crumhorn and bassoon. Richard had seen the crumhorn, a Renaissance instrument with an enclosed double reed and fingering like a recorder (but unable to be overblown by virtue of its narrow cylindrical bore, curved at the end — hence the name, which means 'bent horn'), at a concert at Kingston Polytechnic given by the late David Munrow's Early Music Consort, and had persuaded Brian to take him to London's Musica Rara instrument store to buy one. Richard loves the sound of this instrument; it could be described as sounding like 'a bee... buzzing in tune.' The trio began to play mediaeval music, and loved it; 'Except,' says Richard, 'when the audience threw food at us 'cos they wanted rock 'n' roll!' An occupational hazard for the mediaeval muse. Richard had in fact bought a soprano crumhorn while he was at school, but the trio was the first opportunity he'd had to play one in front of an audience.

The trio shortly evolved into the group that became known as Gryphon; Richard introduced schoolfriend and acoustic guitarist Graeme Taylor, but Graeme and Chris didn't get on, and Chris finally left, two gigs later. The embryo Gryphon spread its wings and began to do the odd folk club, and a couple of other restaurants. Brian was amazed one night at such a venue when the manager came up and sternly asked him to turn his instrument down. He even fingered the bassoon all over to try and find the volume control!

At this point, Dave Oberlé, the percussionist, came on the scene. Richard knew him socially, and when his exceedingly heavy-metal band Juggernaut split up he phoned Richard to see if they needed a percussionist. Richard was a little worried about the effects of introducing percussion — a bit too close to an ordinary rock group, perhaps? How would the drummer of a sado-masochistic college band, used to playing against 200W Marshall stacks make out in the fragile, delicate world of Gryphon? But Dave brought along a couple of bongos and a tambourine, and everything fitted into place. He could sing, too — useful.

Gryphon did a demo tape — not so much for a record deal, but to get gigs — and one day Transatlantic Records phoned up and offered the band a deal. Their manager had, in fact, approached EMI and Island, because the band thought an album would be a nice thing to do, but they'd got a very lukewarm reception. They'd given up, until the call came and the band signed with Transatlantic — 'Our first big mistake,' says Richard.

The first album was produced on a combination of 4-track Teac (for the smaller tracks) at Riverside Recordings, and 16-track at Livingstone studios. Listening back to it now, it's a very good-sounding album. The budget was miniscule, but it sold enough to get in the album charts for one week, soon after its release in about May '72.

The band spent the next few months busily getting excited about becoming stars. The big turning point was the album's one-week appearance at number 28 in the album charts. Yes' manager, Brian Lane, took an interest in the band, and Brian arranged a good deal in the States, and an eventual tour in the US — which didn't actually happen until the third album. But there was one thing wrong: as a result of this interest the band set their sights too high, thinks Richard. 'A mediaeval, English, semi-rock band is never going to be the best thing since the Beatles.' The album did very well, considering the apparently total lack of advertising, and troubles with availability. I discussed it with Richard.

RH: We would have done far better to gradually build up a following on the college circuits, but we moved towards being a rock band so we could be as big as everyone else. Youthful indiscretions.

RE: By the second album you'd added a bass player. Was that a deliberate decision?

RH: Well the main reason was that Brian was restricted by having to play the bass line all the time: sometimes bassoon or bass crumhorn playing the lines was very nice and we still kept that in, but for him to have the responsibility for playing the lower end of these instruments all the time was quite heavy. And it limited Dave to top-heavy percussion work. "So a bass player gave everyone more freedom.

RE: Phil Nestor joined the band at that point?

RH: Yes, and the writing was really on the wall. Pretty soon we were trying to put our intricate acoustic filigrees over a rather conventional rhythm section. We never really combined the two in the best way until the final incarnation of the band, with the last album.

RE: So we come on to the second album, Midnight Mushrumps.

RH: Yes, and this time we wanted to include more of our own material; in fact there's only one number on that album that wasn't written by ourselves — The Ploughboy's Dream. I'd never written before I was in the band; I didn't have the confidence. But I somehow ended up writing the title track which was one whole side.

RE: At the same time you were doing the music for Peter Hall's National Theatre production of The Tempest.

RH: The album was done at Chipping Norton with Dave Grinsted, and I was commuting between the studio and the theatre in London, rising at the first sparrow's fart, going up to London, coming back later in the day and working up till about 2am. After a few days I didn't know whether I was coming or going. I was very involved with the Tempest project, and some of it rubbed off on the album, although there's only one tune that's common to both. But they were both that same kind of magical 'music in the air', a very lovely concept that there could be a magical island where the wind is music and the rustling of the leaves is music. I wanted to combine the impressionist aspects of things like Ravel's Daphnis and Chloe with the sort of Renaissance concepts.

RE: How long did it take to make?

RH: A month; the budget was about £5000. It didn't sell as well as the first album, probably because of lack of promotion. The first album had saturated the 'novelty' aspect of promotion, and the new one was less easy to use for airplay. The first album still gets used for obscure TV and radio programmes. But Mushrumps wasn't like that. It gets used occasionally, but it was very much a big lump, not easily chopped up for airplay. And it wasn't so easy to attach the 'historical bullshit' that everyone loves. You couldn't say that somebody played this tune and danced it all the way from London to Norwich — or wherever — like you could with Kemp's Jig on the first album. It was starting, for the first time, to be music for music's sake; which is always a killer for trying to get any publicity.

RE: What actually happened after that album?

RH: We did a lot of gigs — college dates and a tour with Steeleye Span, which was highly enjoyable, including two dates at the Albert Hall; we found the audiences totally receptive — they didn't go out and buy the albums afterwards, but as they weren't in the shops you could hardly blame them. Then we did the Victoria Palace gig on our own, and headlined at the Old Vic — the first time a band had played there. That was the time you started to get involved.

RE: Then you made the third album, Red Queen To Gryphon Three, again at Chipping Norton.

RH: We were in the thick of wanting to be stars, at that stage. Phil Nestor, the bass player, left during that album. He's a great player for rock music, but some of the lines on Checkmate were killers, and not his cup of tea. I felt sick about that; I was sorry to see him go. That album, and the remaining ones, we always felt that it would be the 'next album' that would make us big. Malcolm Bennett joined the band on bass just as we were about to leave for the next tour. We were desperate for a bass-player. Malcolm was at college with me. At college we'd argued for hours, because he wouldn't hear of anything but the Grateful Dead, and I wouldn't listen to anything but Yes. And I thought there was no way we'd be compatible. But he came along, he played very well, and blended in very well indeed. A real object lesson for people with differing tastes, if you can get thrown together like that.

RE: How did that album come about?

RH: Well I was very much involved with the business side of the band — a real busybody — and when it came to writing I really couldn't get any inspiration. So at rehearsals I got everyone to pool their ideas, we'd go off into different corners and just get writing. Then I'd go away and put them together into structures. It was like a symphony: a rapid, powerful first movement, a very silly Scherzo, with RAF marches combined with crumhorn duets, and then a slow movement almost totally put together by Graeme, Brian and Phil, and then the last movement, pompous, frenzied and joyous, everything a last movement should be. The bulk of the ideas, all the tunes, were together before we went into the studio. I'm a great believer in leaving something big until the studio; if everything's demoed, there's no incentive to get any life into the piece because you know it too well. So although we had the tunes, we left the arrangements until the album, to retain the excitement of the performance.

RE: So the name was thought up afterwards.

RH: Yes; again, music for music's sake is the kiss of death for promotion so we had to have a concept. So poor old me had to sit through Radio 3 musical analysis programmes telling everyone that it was based around an ongoing chess game, very carefully worked out. All tremendously embarrassing. As far as we were concerned, it was just a piece of music we'd written, and we felt that it should conjure up enough pictures in people's minds for us not to have to give it silly titles — but that's life.

RE: And that was the album you took to the States in late '74 on your first Yes tour.

RH: And it was released by Arista there. But the album was still not available. That could have been the 'crushing blow' that started our downfall. They did a good job of promotion,- and we were very well received by 150 000 people at least, and I went into almost every shop I could find, but I saw it in just two stores in New York. And neither had it on display. Mike Klenfner, who's since become head of Atlantic or something, he was very good at arranging promotion, interviews, and so on.

RE: And by that time you'd done the 'single', at Brian Goodman's PSL studios in Battersea, with the Manor Mobile.

RH: That didn't ever get released as a single. You did that didn't you?

RE: Right. How did the whole thing with Yes come about?

RH: Well, two things. The first — and sadly the most important, I think — was that for Brian Lane to get the best record deal, he would have to promise a Yes tour. And secondly, Yes wanted a group they thought they could work with. They'd had a lot of stick from support acts, and their show was suffering. So they thought they'd get a band with somewhat compatible music who wouldn't be a hassle, and it worked out very well. Similarly, on the British tour in early '75, they wanted the tour to go as smoothly as the American one had. Both went very well.

RE: Do you think you've been influenced by Yes, musically?

RH: I' m certain of it. I almost regard Yes as an instrumental band — no offence to Jon Anderson, but I think his lyrics are there for the sound, to make his voice come through as an instrument. Colour, really, is their ace card. I suspect some of their material wouldn't be that strong if done by a single acoustic guitarist and singer, but it's brilliantly arranged, full of excitement, full of light and shade, full of colour, and they also put on a superb live act that's an example to anybody.

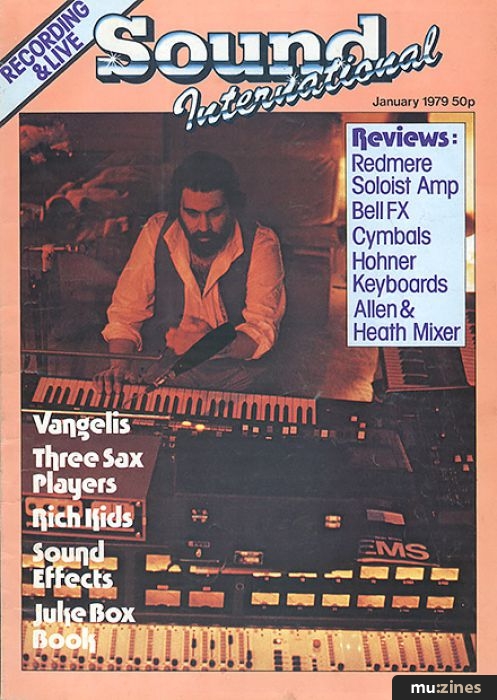

Gryphon at the time of the final album, Richard bottom left

RE: And of course, after those tours, we went down to Sawmills and did the fourth album, Raindance.

RH: That's right; a very enjoyable time. In fact there was a mini-crisis in between, because the group very nearly split up. We were very dejected, and we were told that we were obliged to make another album, for the States. We later found out that the States would have been delighted not to have had another album. They never released it, although they forked out $150 000 or so for it. But we were told that so that the 'powers that be' could get their cut of the $150 000 we had to make another album. And it worked out very nicely. We thought we were a dying operation, and we threw all our restrictions to the wind, and as a result enjoyed ourselves a lot more. And we came out with an album that was just as much a part of our plans. We did go overboard in one or two places, and Transatlantic cut the album up a lot, there were great arguments with Nat Joseph on the phone, when he threatened not to pay.

RE: And when they'd said: 'Make two singles in the first week or we'll cancel the time', and then after the LP was almost finished and we were £500 under budget they threatened to bring it back to London and mix it in an evening with an engineer and producer who'd probably never heard the band, let alone the music.

RH: That was a 'bad scene', but it knitted the group together quite fantastically. There's nothing like a bit of strife, Us and Them, to bring a band together.

RE: A lot of that album was written 'on site'.

RH: Oh, yes, we only had about ten minutes written before we went down there. But then if you're going to write an album on spec, there's no better place than Sawmills. We made such good use of the environment, not just in the recording sense, as you know very well, but in the writing sense. It was very nice, for example, for Graeme to be able to go out, and just sit by the water with his guitar, writing.

RH: It's a great source of annoyance to me that Graeme's song, Ashes, was removed from the album — it really caught the atmosphere of the place.

RH: Yes, I' m a bit unsure about a couple of the other tracks that weren't released: a couple of them weren't quite good enough...

RE: Well at least one was mixed when I was on my last legs, and I just mixed it appallingly.

RH: It was unbelievable. Nobody should be asked to work under that kind of pressure. Certainly not people who have to rely on their ears and their brains. It was sad.

RE: How do you feel about the albums now?

RH: Well, I listen to them infrequently. I have fond memories of the excitement of doing them; I think 'That's really nice...' We were all very young — on all the Transatlantic albums, at least — there are rough edges, but they make good listening, all of them.

RE: Are all the albums still available?

RH: Yes, they are, and I hope they don't get deleted, because they'll always be of interest to somebody.

RE: It was a pity about the cover of Raindance — it was really appalling.

RH: Yes, a real indiscretion. I want to try and talk to Logo about reissuing it with another cover.

RE: The original idea, perhaps, with the pictures of Sawmills?

RH: I'm going to talk to Malcolm about that — he took all of them.

It was all pretty awful. We were given a more-or-less free hand with the packaging of the first three albums, and the first one we weren't given a free hand in was a disaster. It was like Transatlantic's punishment for upsetting them. A record company will never take the personal interest in an album that the band does, and that's what it was. 'You've been naughty boys and we're punishing you by not letting you design your own sleeve.'

Gryphon went their separate ways after that time; Graeme and Malcolm were totally disillusioned by the treatment received from Transatlantic. I was being very heavily courted by Transatlantic to become a solo artist; suggesting things like to make another Gryphon album — or another three, because the five-year contract was extended to seven with the American deal. We were to make another album, but it would be a 'Richard Harvey and Gryphon' album, and I didn't like the sound of that at all. After that it would have been solo albums, and 'you can let your friends play on them if you like'.

RE: By this time you'd done the Divisions on a Ground album.

RH: That was round about Red Queen — it's very blurred in my memory. That was one of the nice things that Transatlantic did; they let me do a classical recorder album. And their confidence has been repaid by quite decent sales.

RE: That album earned you the title of being one of the, if not the, world's best recorder players.

RH: Well, people were saying it, they might have been wrong. But if any album was about to start my solo career off, that was the one. I was glad about that. It caused me not to write Transatlantic out of everything. There were people there who had some spark of integrity, so I didn't write them off 100% - just about 98%! That's good for any record company, isn't it?

So Graeme and Malcolm left; they were fed up and I don't blame them. Graeme went off to join the Albion Band; and I couldn't stomach the idea of the next album being a 'Richard Harvey and Gryphon' album. So I foolishly bartered all my publishing to Transatlantic in order to get the band out. I put a new band lineup together, in two layers: the first layer was Brian, Dave and myself, the original band, then we got a guitarist, bass-player and drummer. The drummer was Alec Baird, from Contraband, another Transatlantic band who'd had the carpet pulled away from under them, a good drummer, very strong; Jon Davie, who was playing in a pub band locally and worked for the GPO, a very good bassplayer and absolutely essential to the operation; and Bob Foster, a guitarist. He was the only one of the band who left before the band had to fold up anyway. He was a classical guitarist, masterful technique, but there was a personality clash, and he departed shortly after the Treason album. We went to EMI: I was looking for a record deal, and I'd approached Atlantic and A&M, through Yes, and not made much headway, but I bumped into Mike Thorne, ex-Editor of Studio Sound (incestuous, isn't it!) in a wine bar, and he said he was now an A&R man at EMI, and why didn't I come and see him! So we went over to EMI and made Treason.

RE: Where was that made?

RH: Against my better judgement, at The Manor, Wessex, and Abbey Road.

RE: Why do you say that?

RH: Because I think that where there's an imbalance of interest, between time and sheer technical quality, one should always go for the time. I would say that when you consider the astronomical cost of The Manor — it's not for mortals like us, it's for the 10ccs, Elton Johns, and Rod Stewarts of this world — so many hundreds of pounds per day; so our budget, big as it was, could only allow us 2½ weeks, at a push. That meant rushing. If you really want to enjoy it, and play well, and be relaxed, you need time. We were killing ourselves: Mike and I, particularly, were just dead at the end of the album. By the time we mixed the album at Abbey Road we were working such long hours that I had to stay in a hotel nearby, I was too knackered to go home. No-one should work in those conditions. And that budget would have given us three months in Chipping Norton — £30 000 — it makes my eyes water. I mean the album turned out fine, considering, but I think it could have been far, far better. We could have got as good recording quality with more time...

RE: I think the recording quality could have been better. It was OK in solo passages but when everything was playing at once it was very muddy and indistinct. I put that down to the monitoring at Abbey Road. It was fine in the control room, but outside a lot got lost.

RH: No real clarity. Nothing jumps out and grabs you. There's a few Black Holes in it. Vocals, a horrific example; that either can be there or can't be, if you listen. Some are so indistinct that you can't hear them unless you listen very hard. They're loud enough, they just don't come through. But we were shattered at that time. My memories of that album... we'd listen to a mix and I just have a memory of these blurred boxes jumping around in front of my eyes with sounds coming out of them and if I could hear everything that must be OK, and we'd go on to the next bit.

RE: And what happened after that? Nobody seemed to hear of Treason.

RH: The album would never have been released but for two major factors. One was Mike's involvement, which was absolutely invaluable. That was the first time he'd ever done any production, I think... and whatever pitfalls were caused by that were totally eclipsed by the fact that he was totally behind the album all the way. Also, Nick Mobbs was very partial to several tracks and put his influence behind it. But I'm sure that if it had been left to the marketing department of EMI it would never have been released. We did a single of one of the tracks, did it the way we wanted it, and we were very happy; that didn't get released, and we had to redo it, in a really watered-down version, before they'd release it. Even then, the pluggers refused to plug it. They thought their reputations were at stake. The album's done about as well as Red Queen To Gryphon Three, our worst selling album.

RE: Why's that? Promotion again?

RH: Yes, there's a world of difference between Transatlantic and EMI, because Transatlantic never had the money to splash out on full pages and radio ads, they had to rely on radio, TV and press writeups for promotion. EMI don't have to, and their promotions department know they don't stand a chance with our type of record — they're more pleased when they get a writeup for Queen in the News Of The World - that must be really hard. Also things weren't doing well gigwise. That was when New Wave was starting to emerge, and it was that which finally killed us off. Not the nature of the music — purely because the record companies were persuading bands who were quite well-known to go out for £50 a night, which completely destroys the kind of ideals you have as a live gigging band. We knew how much we had to make to go out and break even — when we cut down to a one-man crew, when we were back to doing our own humping again, we could actually break even at about £180 a night unless it was a one-off in Scotland. And we weren't overcharging: two drummers, lots of woodwinds, a good-sized PA, and lots of keyboards — a six-piece — was a lot to cart around. But social secretaries are only human, and if they get a well-known band for £50, they'll go for it, make a lot of money. But at that time we'd become definite that we couldn't take any more record company handouts — not that there'd have been any, probably — we didn't want to live on borrowed money, and we were well-used to not seeing our royalty cheques, so we were quite a rarity — a large-scale band making money on the road. There were a few bands like that but they were mainly four-piece outfits, and we had far more than that to cart around. And that just put the nail in the coffin. We couldn't ask our band members to get a job in the summer, or whatever — we'd done it once too often and we had too much self-respect to ask each other to do it again — you can't have much dignity as a professional musician if you have to serve in the pub at lunchtime. So that was the last straw. And EMI were saying they'd quite like a solo album... we don't really want another Gryphon album — same story again.

By this time Gryphon was going down the drain, so I thought I'd get in while the going was good. I took some ideas to Nick Mobbs, some acoustic tracks, and he said that he'd actually prefer something more along the lines of Jean-Michel Jarre... he was top of the charts at the time. And I asked if he'd like me to make Oxygene. And he said, well, no, but nice and electronic, lots of whizzing about... And I thought: Oh, no; if I'm going to be a solo artist, I have to do my own style. If I have to enter the world of Kraftwerk and Jean-Michel Jarre, I won't do it as well. Yet there are things I could do that they could never do. So what's the point? And they said that they'd leave it at that. And Brian Lane pleaded my case, and asked for £50 000 for an album... that might have had a little to do with it.

Continued Next Month

Series - "Richard Harvey"

Read the next part in this series:

Richard Harvey (Part 2)

(SI Feb 79)

All parts in this series:

Part 1 (Viewing) | Part 2

Publisher: Sound International - Link House Publications

The current copyright owner/s of this content may differ from the originally published copyright notice.

More details on copyright ownership...

Artist:

Richard Harvey

Role:

MusicianBrass / Wind PlayerComposer (Music)

Brass / Wind PlayerComposer (Music)

Composer (Music)

Series:

Richard Harvey

Part 1 (Viewing) | Part 2

Interview by Richard Elen

Help Support The Things You Love

mu:zines is the result of thousands of hours of effort, and will require many thousands more going forward to reach our goals of getting all this content online.

If you value this resource, you can support this project - it really helps!

Donations for December 2025

Issues donated this month: 0

New issues that have been donated or scanned for us this month.

Funds donated this month: £0.00

All donations and support are gratefully appreciated - thank you.

Magazines Needed - Can You Help?

Do you have any of these magazine issues?

If so, and you can donate, lend or scan them to help complete our archive, please get in touch via the Contribute page - thanks!