Magazine Archive

Home -> Magazines -> Issues -> Articles in this issue -> View

Steinberg Cubase | |

The new heir to the ST sequencer throne?Article from Sound On Sound, August 1989 | |

After a change of name and a long wait, Steinberg's successor to Pro24 is finally here. Has it been worth the wait? David Hughes thinks so...

After a change of name and a long wait, Steinberg's successor to Pro24 is finally here. Has it been worth the wait? David Hughes thinks so...

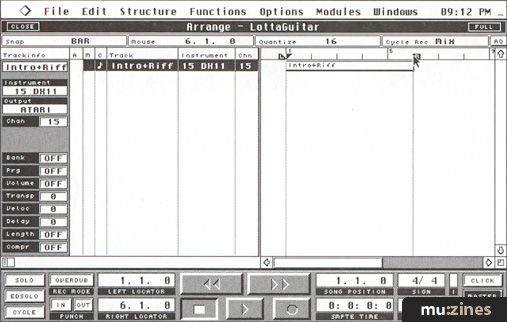

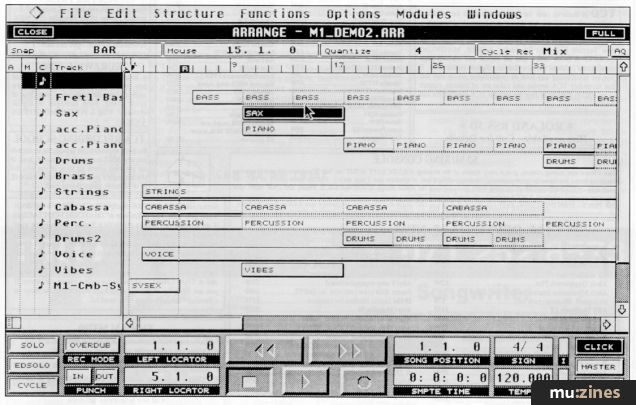

Cubase main screen.

Steinberg are probably best known as the originators of Pro24, a 24-track desktop MIDI recording program, which practically set the standard of what a computer sequencer should or should not do in a recording studio. The influence of this program is tremendous, and extends right the way through the industry. However, Pro24 has been with us for a number of years now and is perhaps starting to look a little long in the tooth when compared to some of the more recent programs, such as C-Lab's excellent Notator.

Cubase, the latest offering from Steinberg, comes as an obvious successor to Pro24. It boasts a wealth of features, a new graphic user interface and, as the centrepiece of the program, a new 'operating system' called MROS. That's definitely a piece of jargon that will usurp 'workstation' as the current industry buzzword! (Look to the side panel for more information on operating systems). With the release of Cubase and MROS, Steinberg appear to be right out at the front of the pack, ready to set another standard which I feel a lot of software companies will have trouble trying to match.

WHAT YOU GET FOR YOUR MONEY

The review package contained a number of goodies. There were two 3.5" double-sided disks, one containing Cubase itself, the other a simple slide show demo program which provides a general overview of the Cubase system. Also provided is a copy protection dongle and the user manual. It's all attractively bundled together in a very professional beige box-like affair. My only criticism of the general packaging is that the weighty, ring-bound user manual tends to break free from its moorings rather easily.

Steinberg's previous attempts at a user manual were, from my point of view, a total disaster. Happily, this is not the case with the Cubase manual. I have never come across a manual that is as detailed, as helpful and as readable as the Cubase one. It starts by giving a brief introduction to the concept behind Cubase and then leads you into a simple recording session.

After quickly flicking through the manual the next step was to get the program up and running. The first thing you must do is fit the software protection key - or 'dongle', to use the common computing parlance - into the Atari's cartridge port. The dongle prevents any unauthorised duplication of the program, although this doesn't stop you from making as many backup copies as you need - they just won't run without the dongle in the cartridge port.

It was at this point that I discovered the first major let down with Cubase. It does not support a colour monitor. Oops! I can't help but feel that Steinberg have shot themselves in the foot with this. All of you folks using colour monitors will have to think about buying a standard Atari monochrome monitor or else look for a different program.

The Cubase disk contains even more goodies. There's the Cubase program itself and a number of associated data files; a 'switcher' program, which allows you to have multiple programs in memory at the same instant (provided you have enough memory, that is); a desk accessory program called Satellite, and a couple of demo song arrangements. (See side panel for details of Satellite.) There's also a 'read.me' text file which contains a number of useful hints and tips about the package in general. The contents of this file vary from version to version, and therefore it's advisable to read this through before you start up the main program.

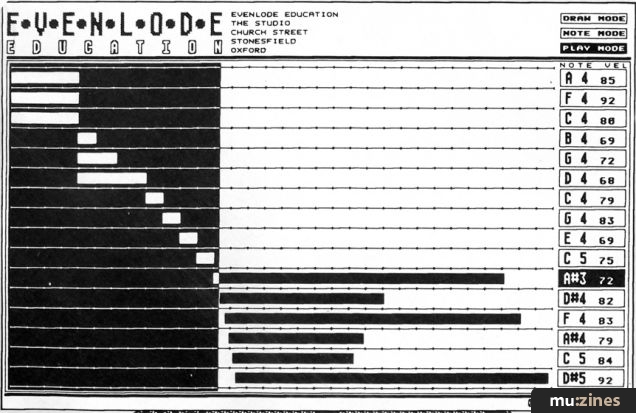

Score Edit window.

BOOTING UP

Loading Cubase from a standard ST floppy drive seems to take forever, but actually takes just under a minute. Once up and running, the default Arrange window opens on the screen.

One of the first things you notice is that Steinberg have reset the character set to something close to the 'Chicago' font used on the Apple Macintosh. I strongly prefer this font to the rather 'stubby' character set adopted by Atari and used on most other ST software. It's interesting to note that any desk accessories, such as the aforementioned Satellite program, which use the standard Atari font also appear in a new guise. So be prepared for a few surprises!

The main screen retains very little of the general appearance of Pro24. There are the usual 'tape transport' functions, bar count and elapsed SMPTE time etc, which are pretty much par for the course these days. The array of bargraph meters which Pro24 used to indicate the amount of activity on its 24 tracks are no longer present. In their place are two similar bargraphs which simply show the activity on the MIDI In and Out ports. Shame about that, but never mind.

In fact, the main screen at first appears to be very sparse in nature. The Arrange window is divided into two halves: to the left is the Track list and to the right the Part display. The title of the piece is shown at the top of the window. It's also possible to have a number of Arrange windows resident in memory at the same time. To select an alternative arrangement, you simply go to the relevant drop-down menu and click on the required title. Couldn't be simpler. The Track list allows you to assign an appropriate name, instrument and MIDI channel to each track. To the left of the track list you have the track mute field. Clicking the mouse within this region effectively silences the selected track. Talking of tracks, with Pro24 you were limited to just 24 tracks; with Cubase you can have up to 64 tracks within an arrangement.

As the name suggests, the Part display indicates the position, in time, of a collection of MIDI data. A Part is the most fundamental element that you can have in Cubase, and Parts can be made up from just about any type of MIDI information. The ability to manipulate data at this sort of fundamental level is one of the strengths of Cubase. A Part can be created in a number of ways. Firstly, data can be recorded via the MIDI In socket. It's also possible to create a Part from one of the drop down menu options, ready for modification in any of the four edit windows. Part data can also be generated by copying between different Arrange windows using the 'clipboard' utility. If you've used a word processor before, you'll probably know this function under the more usual name of a Cut and Paste edit buffer.

Recording a Part is a simple process. It's just a matter of specifying the start and end point of the piece you want to record - represented in Cubase as a pair of vertical lines drawn within the Part display - and clicking on the record icon. Cubase will allow you a straightforward two bar count-in or play back from a preset position ready for you to 'punch' into an existing piece. A third vertical line - the song position pointer - scrolls from left to right as the sequence plays. Cubase will also assist you during the recording process, if you require. The 'Human Sync' option will attempt to match the tempo at which you play to the tempo selected on the front panel. The degree to which Cubase will help you can be selected from one of the drop down menus. Furthermore, you can select a 'Chase Events' function which will step backwards through any previously recorded track data searching for the last MIDI Program Change message, so that you always begin recording with the correct patch data set up on the relevant synth or sound module.

Most of the functions within Cubase can be selected either from the Atari's keyboard or the mouse. For instance, you can set the left and right locators from the keyboard by typing 'L' or 'R' followed by a suitable value, or you can set them with the mouse by simply clicking above the required position with the left or right mouse button, as appropriate.

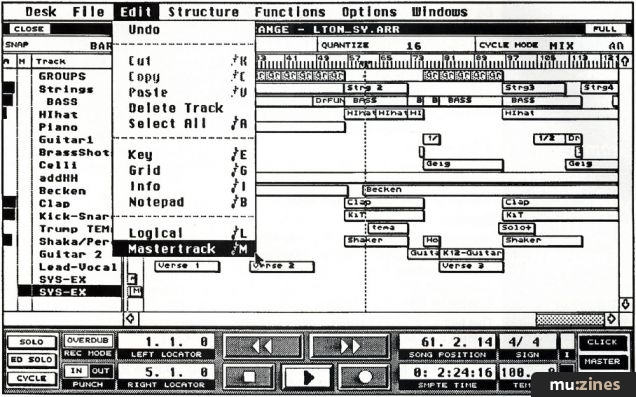

Grid Edit window.

Cubase's major claim to fame is that it operates in 'real time', meaning you can modify any of the parameters of a song while the piece is playing. [Intelligent Music's RealTime sequencer is also capable of this feat - Ed.] To emphasise the real-time nature of this feature, it's possible to reposition the locators, copy, merge, delete and create Parts within the Part display while a song is playing. It's also possible to modify Part data from any of the edit windows and hear the effects of any changes on the piece as a whole without stopping and re-starting the main sequence. The Part display also scrolls whilst the song plays and each screen is redrawn with the most amazing speed. Although Cubase retains the windows, icons, mouse, pointer (WIMP) approach used in standard GEM programs, it's important to note that the graphic interface used is, in fact, Steinberg's own version of GEM. Digital Research's GEM is simply too slow for the job!

COMPATIBILITY

At first sight Cubase doesn't appear to have much in common with Pro24. However, operationally, the two are very similar. Existing Pro24 owners will have little trouble relating to this package.

My next step was to port a number of Pro24 songs over to the Cubase environment. In theory, you shouldn't encounter any problems in doing this. However, I discovered that a number of my Pro24 files would not transfer and actually caused Cubase to crash. A quick phone call to Steinberg Technical Support indicated that the review copy of Cubase was a May 1989 release of the program and that the bug should have been fixed in the June 2nd version. In fact, the bug wasn't fixed in this version either, though I have been assured by Evenlode Soundworks, the UK distributors of the program, that Steinberg are aware of a number of problems with Cubase which should be fixed by the time you read this.

To be fair, this bug isn't so much of a problem with Cubase. It's actually caused by Pro24, which fails to verify that the data it saves to disk has indeed been correctly recorded, and since Cubase carefully checks all of the data that it saves and loads to and from a disk, the file couldn't be retrieved properly. Since the program was supplied for review purposes, this wasn't such a serious problem at the time. I still had my Pro24 package to hand and, using a process recommended by Steinberg Tech Support, I managed to remedy the defect so that Cubase could import the suspect files. This could cause problems for users intending to upgrade to Cubase from Pro24. When I discussed this with Steinberg Tech Support, I suggested that Cubase might be a little less fussy about the data imported as Pro24 files. Their reply was that - as an added safeguard - you should re-save all of your existing Pro24 songs as MIDI File compatible song files before you trade-in your Pro24 package. This makes a lot of sense.

Having successfully ported a number of Pro24 files over, the next step was to simply put Cubase well and truly through its paces...

DOWN TO BUSINESS...

Cubase retains the Pro24 concept of Songs, Tracks and Parts and each Cubase Track can be named and assigned to a particular MIDI channel. You can also assign an instrument name to a particular Track. If you have a Steinberg SMP24 SMPTE-MIDI processor at your disposal, you can assign the output of a Track to any one of its four available MIDI Outs, as well as the normal Atari MIDI Out connection. Furthermore, you can route the output of a given Track to another MROS-compatible program entirely via a sort of 'virtual' patch cable.

Each Track is made up from a collection of Parts, and any Part may be highlighted for editing purposes simply by clicking above the Track name with the left mouse button. The Track is then highlighted in reverse video ready for any subsequent operation. Patterns may be manipulated in the same way. Part data may be moved from one Track to another simply by dragging the relevant Part - represented on the Part display by a simple rectangle - to the required destination. To duplicate the Part completely, you have to hold the 'Alternate' key down on the Atari whilst dragging the Part. Repeating this for each Part can be a bit of a chore, although it is possible to drag whole groups of Parts around the Arrange window very easily, which greatly simplifies the writing process.

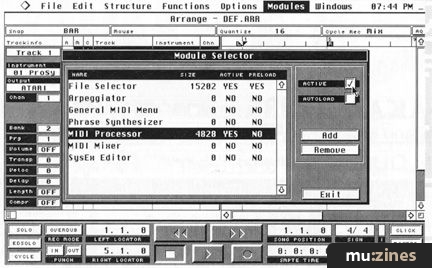

Drum Edit window.

Clicking on the right mouse buttons reveals a drop-down toolbox containing a number of useful icons which really simplify the manipulation of data. The number of tools available depends upon which particular window is active at the time. There are eight such tools available in the Arrange window, for example. To select the required tool, you've got to hold the right mouse button down - the toolbox then appears - and then move the cursor so that it highlights the tool you're after.

This takes a bit of practice, but once you've perfected the technique, updating the Part display becomes child's play. The icons are very well drawn, although in some instances their function is not immediately obvious. For instance, the 'Q' icon left me a bit puzzled - it's actually for matching quantisation levels between different Parts. Other functions are readily apparent. You can cut a Part in two using the 'scissors' icon and repair the damage using the 'glue' icon. Deleting an unwanted Part is simply a case of selecting the 'eraser' icon - the mouse pointer actually takes on the form of the eraser icon - and clicking over the offending Part. Very useful.

One of the later additions to Pro24 was the ability to create a Song by manipulating groups of Parts together. Cubase retains this concept as 'Group Tracks'. Basically, a Group is a collection of Parts which constitute perhaps the chorus of a song or possibly the instrumental break. The advantage of this way of thinking is that you can quickly change the structure of a piece simply by manipulating the individual Groups which make up the Group Track. You can have a number of different Group Tracks within alternate Arrange windows. Once you get a grip on this option, the creation of 12" disco mixes, party mixes, rap versions, etc is very easy. I liked this feature, because like most people I'm rarely happy with my first attempt at any given arrangement. Come to think of it. I'm frequently less than happy with my final arrangement, too! Consequently, the ability to restore the original is very welcome.

VISUAL EDITING

The edit options within Cubase are also one of the strongest points of the program. Editing a Part can be accomplished using any one of the plethora of visual editors available within Cubase which, thankfully, retains all of the edit options used in Pro24 - Grid Edit, Score Edit and Drum Edit. To that list it also adds a Key Edit option. It's also important to note that each of the original Pro24 edit windows have been given something of a facelift, though they remain operationally very similar. My main criticism is that, occasionally, there is just too much information presented to the user at any one instant - probably the reason why Steinberg chose not to accommodate a colour monitor - and I found myself scuttling back and forth between the edit pages and the manual in search of one function or another which was readily available on my trusty Pro24. Actually, I suspect that this is a problem which would resolve itself during the learning curve that must always be anticipated with a new product like this. Graphically, the edit windows are excellent. The wealth of detail is truly stunning.

It's worth running through the basic functions and operation of some of the edit windows for those who are not all that familiar with the idea of an edit window. Score Edit and Drum Edit are pretty well self-explanatory: Score Edit simply displays the MIDI information that makes up a Part (or Parts) using standard musical notation; Drum Edit simplifies the generation of percussive Parts and assists in the creation of new drum sets.

Grid Edit is a little more complex. MIDI data of any type is represented as a series of sequential events running down the page. The data is presented in two ways. Firstly, it's shown in a simple numerical format with the message type, its position within a Part, and any associated values grouped together. Secondly, each MIDI event is depicted graphically as a rectangle within the edit grid. Manipulating the data within an edit page is simply a case of opening up the toolbox - again, with the right mouse button - and selecting the required tool.

It's also possible to move an event around the edit grid just by clicking on it with the left mouse button and dragging. I'd also like to emphasise that, although you do tend to spend a lot of time within the edit pages - unless, of course, your playing is actually spot on - they are remarkably creative tools as well. As a simple example, I always used to have a great deal of trouble playing along with the standard metronome tick. It was either too loud or too quiet! With the Grid Edit page - and, equally, the Drum Edit page - I can quickly produce a simple regular hi-hat pattern, using the Fill function, that I don't have any trouble working with. The same process works equally well for simple pulsed bass patterns.

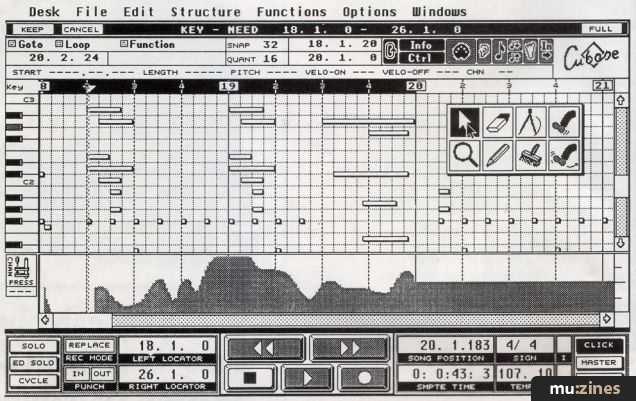

Cubase main screen showing various windows.

Key Edit is a useful addition to Cubase. Although most of the functions within the Key Edit option are duplicated in the Grid and Score Edit pages, it is an extra option which will make life just that little bit easier. The Key Edit page consists of the usual title and function bars associated with each of the other edit windows, and a standard chromatic piano scale drawn vertically at the left-hand side of the window. The main screen is populated with an edit grid, within which all of the note events are represented. At the bottom of the window is a bargraph which depicts the key velocity for each note as a vertical line. If you go to the toolbox and select the 'pencil' icon, it's possible to re-draw the individual key velocities, which greatly simplifies the creation of crescendo and diminuendo effects. Superb! Also, as the mouse is moved around the edit grid, the relevant key on the piano scale is highlighted. This is also true when you play a few notes on your MIDI input device. What's more, there's a feature within this page which actually recognises the shape of the chord that is currently held. Great fun!

This is one of those features that pushes you further and further into the musical side of the machine. My music theory was never very hot - but just having this feature is a real incentive to get down to some real hard learning a.s.a.p!

It's important to point out that you can have several edit pages open at the same time. However, even though you can jump between these windows while the main sequence is playing, only the currently selected window is updated graphically. All other activity within the remaining windows - and that includes the Arrange window - ceases. The tape transport functions are always updated, no matter which window is selected.

Having come this far into the review, it's easy to see that I'm becoming more and more enthusiastic about Cubase - and I haven't yet explained several of the other features that I singled out as being worthy of mention. The problem, if you can call it a problem, is that Cubase is vast! The attention to detail is very impressive and Steinberg seem to have listened very carefully to the user feedback they have received since Pro24 was released. I can give a few examples of this attitude...

Suppose you're using some kind of MIDI input device that doesn't have a Local Off function. If this were so, then every note that you play on (say) your keyboard would be echoed straight out via the MIDI Thru socket. You could solve the problem by switching off the MIDI Thru function on the Atari ST, but that would mean that data destined for any modules you might have connected would never reach its target. Steinberg have thoughtfully created a function which allows you to switch off the MIDI Thru connection on a single channel - which means you don't get double notes and consequently none of the hassle that usually results. Nice touch!

One of the fun things you can do with Pro24 is create echo, delay and flange type effects simply by creating a copy of a specific Part and then adding a delay (time offset) to the second Part. You can make the resultant sound more complex still by creating further copies of the original Part and doctoring the delay between each Part. This is a bit fiddly to do and time-consuming to set up, but is still very much less expensive than buying a second or third digital delay unit. It's therefore good to find that Steinberg have included a MIDI effects processor as an option within Cubase, available from one of the drop-down menus, which makes the rather complex setting up procedure simplicity itself.

THE SWITCHER

There was one aspect of the Cubase system that I did find a little disappointing, and that was the 'switcher' utility. Theoretically, this package should allow you to have up to 10 different application programs resident within the ST at any onetime, providing there is sufficient memory available at the time. I managed to beg an Atari Mega ST2 for the purposes of the review, which is apparently the minimum configuration for the switcher to work correctly.

Key Edit window.

The set-up procedure for the switcher isn't very complicated at all. Essentially, you just tell it which programs you want to use and how much memory they require in order to run properly. In the switcher tests, Cubase loaded and executed perfectly every time I went to use it. However, I did encounter problems when I attempted to run a number of other programs from this page. Steinberg's own Synthworks editor for the Roland D110 would not load properly when the memory allocated to it was less than one Megabyte. When it did load up, it refused to proceed past the title display because its copy-protection dongle was not in place. This is because the Cubase dongle already occupied the ST's cartridge port and it isn't advisable to remove a dongle when the machine is powered up. Therefore, if you want to run multiple Steinberg programs from the switcher then you will need to purchase one of Steinberg's own 'dongle expander' modules and insert it into the cartridge port.

WHERE DOES CUBASE FIT IN?

It's interesting to look at where Cubase fits into the existing music software marketplace. The most obvious competitor - in terms of cost - has to be C-Lab's Notator package. From what I've seen of Notator, which admittedly isn't much, there appears to be quite a bit of common ground between the two programs. Both are highly professional packages - with professional price tags to match! - and both have features which make them very attractive to any class of musician, be they established professional or aspiring amateur.

Although both Notator and Cubase are excellent products, I feel that Cubase does have an edge on Notator. Firstly, it's easier to see what's going on at any given instant - the Notator display is initially quite confusing and a bit untidy. Secondly, Cubase is a simpler package to use from my point of view. I don't want to be unfair to the C-Lab program but I must admit that I was left somewhat bewildered by the shop demonstration I received.

If I have any reservations about Cubase, it's because the review copy that I received from Evenlode did contain a number of small bugs. Most of the problems I encountered were of the type that are eliminated with time. However, some of these bugs were so readily apparent that I'm surprised they were not picked up in the beta-test phase of this product.

I'm a little alarmed by the amount of memory that you now need in order to run multiple music programs within the Atari ST. I used a 2 Megabyte machine for the purposes of this review, and that was only enough to run two programs. Cubase itself won't run on anything less than a 1 Mb machine. If you don't already own a Mega ST and you want to take advantage of the multitasking facilities which Cubase offers, you'll have to consider either upgrading to one of the Mega STs or increasing the available memory in your existing 1040 ST.

There are a number of companies offering such upgrades as 'simple to fit' expansion boards, although I would be a trifle cautious about putting so much RAM in a machine such as the 1040 because of the effects of heat dissipation on the other machine components. Third Coast Technologies of Wigan ((Contact Details)) offer such an expansion board in a number of differing configurations which can be tailored to fit most purses. Ordinary 520 STFM machines can be upgraded to the normal 1040 ST configuration simply by adding a few RAM chips to the main board and either an internal or external 3.5" double density disk drive.

Finally, I also would have liked to see the Cubase scorewriting option but this was not yet implemented in the review program. It should be available at a later date.

VERDICT

I like this program a lot. Cubase is a natural successor to Pro24 and I would strongly recommend Cubase to any existing Pro24 owners, who should remember that they can save quite a substantial amount of money if they take part in the part-exchange scheme that Steinberg are offering. I would also recommend this program to those musicians looking for a fully professional system with the potential for expansion. Cubase has this in abundance. I've used the review package for over a month now and Steinberg will find it difficult to prise it out of my hands. I feel that I've written some of my best music with Cubase, and consequently don't want to lose a single note of it. I enjoyed the sheer depth of this product. You simply won't exhaust the possibilities in a single night. It will take a great deal longer than that, I promise you.

The general concept behind Cubase works well. It's easy and fun to use. I also like some of the esoteric touches that Steinberg have included, such as the cleverly drawn icons. For instance, the step-time input icon within the edit pages is a 'foot'; to modify the amount of pitch bend applied to a note you select a small 'joystick' icon. These may not seem important points but they encourage you to look further into the system as a whole, as well as raising the odd smile!

Obviously, I couldn't possibly delve into every facet of the program simply because there isn't space. I feel that I've missed out a number of elements that deserve more attention but then I said the same thing when I reviewed the Synthworks D110 editor. Cubase has a lot of potential. It has lived up to and actually exceeded my expectations. I hope Steinberg fulfill their promise and push this system to its logical conclusion.

FURTHER INFORMATION

£500 inc VAT.

Evenlode Soundworks, (Contact Details).

OPERATING SYSTEMS

Operating systems are, by definition, fairly complex beasts which usually lurk deep within the bowels of the machine. And, joking apart, this is actually the best place for them! The fundamental principle of the operating system is that it keeps the evils of your particular machine hidden from you.

As a simple example, suppose you want to write a program which loads a file of data into memory. In most cases, you might write a line of BASIC which might look something like: LOAD "Mickey-Mouse". Consequently, the computer loads the file "Mickey-Mouse" into its memory ready for any operation you might want to perform. As a normal user that's usually all you want to know about the process. But, just suppose you had to do it from scratch! The thought is usually enough to make even the most experienced analyst slope off to the nearest watering hole. However, it does illustrate the point.

Another example might be a real-time clock, the kind of facility that is commonplace on all but the simplest of machines. Well, the Atari ST keeps a record of the date and time internally, which must be reset each time the machine is switched on. Other machines use a hardware circuit stashed away in a remote part of the main circuit board. But is this really important? Not to me, I only want to know the time!

In early commercial machines, usually all that existed between you and the guts of the computer itself was the software 'monitor'. This was a simple program that could provide a number of functions such as the ability to read a program card, dump a line of text to a teletype, etc. As the machines developed so did the software monitor, to the point where the monitor became responsible for managing much more than simple input and output of data.

Suppose that you have a particularly slow output device like my printer, which sits chugging away in the corner of the room typing a couple of characters a second and generally having a very easy time of it all. The problem with this, as I'm sure many of you will have noticed in the past, is that the main computer is stuck doing very little indeed. Wouldn't it be better to send a load of data off to a big buffer area somewhere and then let the printer empty it at its own rate while the computer gets on with something else more important. This is exactly how the principle of multitasking came about. The operating system would manage the buffer for us as well as tell the calling program that the printer had finished its job and that it would quietly like to go back to sleep things off after a good hard bang.

There are a number of alternative multitasking operating systems already available for the Atari ST, such as 'PDOS' and 'Mirage'. MROS - Steinberg's new MIDI Real-time Operating System - is described as being optimised for the input and output of MIDI data, which sounds good on paper but what does it really mean?

To be a true multitasking operating system, MROS must operate in real time and support a full set of features like intertask communications, networking, context switching, etc. Ugh! Just look at all that jargon. Actually, to all but the habitually curious, this will remain completely hidden from the user. The advantages, however, are enough to make your mouth water.

Just contemplate, for instance, running two or three different programs at the same time in the same computer - maybe a voice editor, librarian, sequencer or automated mix-down software. Furthermore, you won't be restricted to using the products of just one company. So long as the programs you use adhere to the MROS protocols - and the signs are that a number of developers are taking a real interest in MROS and its capabilities - you should be able to customise your setup as you see fit using software from a number of different sources.

Furthermore, the Cubase manual states that versions of MROS have also been written for the Apple Macintosh and IBM compatible MS-DOS machines. Consequently, you should be able to use the networking facilities which exist within MROS to pass messages between two computers from different manufacturers in real time. All of this, in theory at least, should be completely transparent to you, the user. Your computer - call it the 'host machine' - would simply regard the 'remote' or 'slave' machine as a source or sink of MIDI data.

Suddenly, the concept of a fully integrated studio doesn't look all that far away, does it? Wonderful things, these computers...

SATELLITE EDITOR

Basically, Satellite works in three ways. Firstly, it functions as a 'macro editor' - to use Steinberg's terminology - which essentially means that it has a simple model of a number of instruments which allows you to edit basic voice parameters such as the attack rate, sustain level, vibrato and velocity sensitivity of a voice without needing a full function parameter editor. Secondly, it operates as a simple voice librarian. Provision is made for other instruments that Satellite doesn't immediately recognise, consequently the utility is definitely of use even to users without Synthworks editors. Thirdly, Satellite functions as a 'pipeline' into the Cubase program itself, which means that System Exclusive messages, configurations, control changes, etc can be recorded in a Cubase track ready for downloading to the instrument whilst a particular song is playing, thus freeing you from any memory restrictions imposed by your instrument.

The nice thing is that, being a GEM desk accessory, it can be accessed from within any other GEM-based program - for instance, a sequencer (which does not have to be a Steinberg product). Bearing in mind Steinberg's delight in copy-protecting as many of their products as is possible, it's interesting to note that Satellite is not copy-protected in any way. Hence, I suspect that it will be copied more times than episodes of 'Fawlty Towers'!

Also featuring gear in this article

Clash of the Titans

(MIC Oct 89)

Cubase 2.0

(SOS Dec 90)

Cubase In-depth

(MIC Jan 90)

Cubase MIDI Mixer - Programming Clinic (Part 1)

(SOS Oct 92)

Cubase MIDI Mixer - Programming Clinic (Part 2)

(SOS Nov 92)

Dream Sequences (Part 1)

(MX Dec 94)

Dream sequences (Part 2)

(MX Jan 95)

Dream Sequences (Part 3)

(MX Feb 95)

Dream sequences (Part 4)

(MX Mar 95)

Dream sequences (Part 5)

(MX Apr 95)

Dream sequences (Part 6)

(MX May 95)

Dream sequences (Part 7)

(MX Jun 95)

Hands On: Steinberg Cubase

(SOS Jan 92)

Steinberg Cubase - Version 3.0 Software

(MT Sep 92)

Steinberg Cubase 3.0 (Part 1)

(SOS Apr 92)

Steinberg Cubase 3.0 (Part 2)

(SOS May 92)

Browse category: Software: Sequencer/DAW > Steinberg

Featuring related gear

An Old Pro - Steinberg Pro24 Amiga

(SOS Feb 91)

Macintosh or Atari?

(SOS Jan 88)

School's Out

(MIC Aug 89)

Software Tracking - Steinberg Pro24 Software

(EMM Sep 86)

Steinberg Cubase Audio

(SOS Nov 92)

Steinberg Cubase Lite - For the Atari ST

(MT May 93)

Steinberg Cubeat

(SOS Nov 90)

Steinberg Cubeat - Atari Sequencing Software

(MT May 91)

Steinberg Pro 24 - SoftwareCheck

(IM Oct 86)

Steinberg Pro24 Version III

(SOS Aug 88)

Steinberg Software Page

(SOS May 88)

Steinberg Software Page

(SOS Jun 88)

Yamaha Hello! Music! - computer music system

(MT Nov 93)

Browse category: Software: Sequencer/DAW > Steinberg

Publisher: Sound On Sound - SOS Publications Ltd.

The contents of this magazine are re-published here with the kind permission of SOS Publications Ltd.

The current copyright owner/s of this content may differ from the originally published copyright notice.

More details on copyright ownership...

Review by David Hughes

Previous article in this issue:

Next article in this issue:

Help Support The Things You Love

mu:zines is the result of thousands of hours of effort, and will require many thousands more going forward to reach our goals of getting all this content online.

If you value this resource, you can support this project - it really helps!

Donations for November 2025

Issues donated this month: 0

New issues that have been donated or scanned for us this month.

Funds donated this month: £0.00

All donations and support are gratefully appreciated - thank you.

Magazines Needed - Can You Help?

Do you have any of these magazine issues?

If so, and you can donate, lend or scan them to help complete our archive, please get in touch via the Contribute page - thanks!