Magazine Archive

Home -> Magazines -> Issues -> Articles in this issue -> View

AudioFrame Grows Up | |

Article from Sound On Sound, January 1989 | |

Although expensive, digital audio workstations are a pointer to the kind of features we can expect to see on the next generation of 'affordable' hi-tech instruments. Craig Anderton takes a look at one of the very latest workstations to appear, the AudioFrame.

Digital Audio Workstations are becoming all the rage in top-class recording and post-production studios. Although astronomically expensive, they are a pointer to the kind of features we can expect to see on the next generation of 'affordable' hi-tech instruments. Craig Anderton takes a look at one of the very latest workstations to appear, the AudioFrame.

About two years ago, industry heavyweights started disappearing on a regular basis and re-appearing in Boulder, Colorado as part of a start-up venture called WaveFrame. At the 1987 AES Convention in New York, the wraps came off, production units of the AudioFrame started shipping thereafter, and the company was on its way. Positioned as a high-end digital audio workstation a la Synclavier and Fairlight, the AudioFrame's under-$50,000 price - not exactly small change, but very competitively priced for what it claimed to do - raised a few eyebrows. Most of those early claims have come true, and the system's current level of operation demands a close look by anyone who works professionally in sound and video production.

THE CONCEPT

The AudioFrame recalls the early days of microcomputers, when systems consisted of a single large box with a motherboard and card cage. Cards were plugged in as needed to configure particular systems. The advantages were, and are, that you need to buy only as much system as you want, and expansion is relatively painless. (I'll attest to the soundness of the concept: my 1979 model CompuPro computer has gone from 64K of RAM to 2 Megs, from an 8080 processor to an 80286, from single-user to multi-user, and from a floppy to hard drive, all by simply plugging in a few boards here and there.)

The AudioFrame system fits in a 10U rack-mount box with backplane and card connectors. The backplane handles 64 channels of high-speed multiplexed audio; information is conveyed from one bus slot to another in 350 nanoseconds, and audio is updated every 22 microseconds (the 44.1 kHz sampling rate standard). The backplane also includes a 1 Megabit per second communications line for handling multiple MIDI streams, SMPTE, and user commands from the central computer (more on that later). Working with, for example, MIDI at such a high internal rate renders the "MIDI's too slow" argument moot, if not pointless. Once MIDI data enters the AudioFrame, it flies from point to point.

Cards currently available for plugging into the mainframe include:

• Studio Control Processor. This communications board drives up to four of the AudioFrame racks and handles (among other things) two independent MIDI input and outputs, SMPTE (linear time code) in and out and VITC (vertical interval timecode) in, house sync, digital work clock and connections for the IBM Token Ring network - an industry standard Local Area Network. These can all be in use simultaneously - for example, another user in another studio can access the system via the Token Ring network, while the system itself syncs to SMPTE and outputs MIDI.

• Analogue-to-digital convertors. Available in 2- or 8-channel configurations, these modules convert real world analogue signals into a form compatible with the AudioFrame's all-digital internal environment. The use of high quality convertors and a 44.1 kHz constant sampling rate insures accurate 16-bit conversion. This board (as well as the output D/A boards) can work with -10dB and +4dB signal levels.

"About two years ago, industry heavyweights started disappearing on a regular basis and re-appearing in Boulder, Colorado as part of a start-up venture called WaveFrame."

• Digital-to-analogue convertors. These output boards convert the AudioFrame's digital signals back into analogue, at a constant sampling rate of 176.4kHz. There are also four stereo AES/EBU outputs for those instances when you want to stay in the digital domain (eg. go directly to digital tape).

• Sampling board. This includes 16 dynamically allocated voices and two Megabytes of RAM - enough for recording 24 seconds of mono audio data. There's also a SCSI-compatible adaptor for high speed data storage/retrieval (more on this later).

• 14 Meg RAM board. For 2.5 minutes of CD-quality sound, add this board to the basic sampler. If that's not enough, you can add more sampler boards for more voices, or more memory for more sampling time.

• DSP board. Using four Motorola 56000 Digital Signal Processing chips, this board is software-configurable to perform a variety of signal processing tricks. Currently, there is software to turn this board into 'MIDICAD', a 16x4x2 mixer with digital reverb (it could also be configured as a 16x8 mixer without reverb). Remember, all this occurs completely in the digital domain, using 24-bit internal processing. Also, 24 channels of digital audio can be transferred from one DSP board to another. We'll cover the mixer in more detail later.

The other essential part of the system is an IBM 80386-compatible computer. This, and a monitor, are included in the system package price.

"You can take a gong sample and transpose it down four octaves - the sound is still clean, bright, and free of garbage."

BUT WHAT ABOUT...

The hardware is pretty sophisticated, but bits, bytes, and speed mean nothing without sound quality, a well-designed user interface, and the software to make it all fly.

Regarding sound quality, it's gorgeous, real, and smooth. The AudioFrame employs fixed sample rate technology, and interpolates literally hundreds of samples in between sample points to smooth out a wave. This gives the effective equivalent of a drastically higher sampling rate, and greatly relaxes the output filtering requirements. You can take a gong sample and transpose it down four octaves - the sound is still clean, bright, and free of garbage. Nobody is going to fault the AudioFrame for sound quality; it's as good as any digital audio I've ever heard come out of a speaker. Pitch bending doesn't produce 'zipper noise', even when 'scrubbing' the sound to find precise loop, edit, and truncation points (and yes, the scrubbing implementation is superb). There's even a track replacement feature if you want to replace existing taped sounds (eg. percussion) with sampled sounds from the AudioFrame.

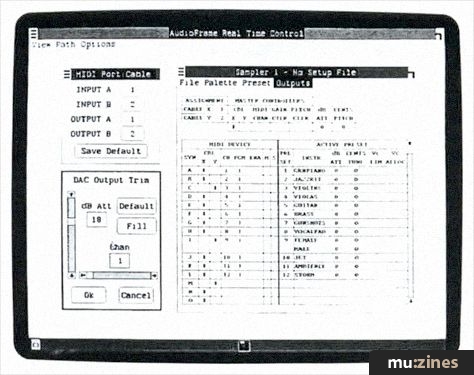

AudioFrame's Real Time Control software simulates a roomful of synthesizers on a single screen.

Sampling also works hand-in-hand with the user interface. The main interface is Microsoft's Windows, and those windows are used very creatively. All parameters for a sampled preset are shown (and are editable) on-screen, including length, transposition range, original pitch, tuning, loop points, envelopes, MIDI channel, and so on. What a relief after scrolling through LCDs one parameter at a time! WaveFrame also claims to be readying a way to print out those parameters for hard copy perusal (since the data is ASCII, it's easy to export to a word processor too). Of course, there are also edit windows as on Digidesign's Sound Designer or Blank Software's Alchemy to edit loops and such, but seeing all parameters at a glance helps identify 'rogue' samples (eg. ones that had to be detuned to hit concert pitch), and greatly speeds up the editing process.

My one major disappointment with the sampler is the lack of onboard filtering. There is a low pass filter to cut down on brightness when samples are transposed upwards, but only three cutoffs are available, and the filtering is not dynamically alterable via envelopes. This is not crucial when sampling only acoustic instruments, but for sampling synthetic timbres, having onboard filters is pretty close to a necessity. Also, polyphonic aftertouch is not supported (but there's not all that much you can assign velocity and aftertouch to anyway). There is one way to help compensate for this; you can record up to seven layers of sound, each triggered by different velocity levels. So, if you want the sound brighter when you hit the keys harder, you can bring in a brighter sample. Still, this is no substitute for dynamic filtering. Although plans are afoot for digital EQ on the sampler, I think we'll have a bit of a wait until dynamic filtering becomes a reality on this system.

VISUAL EDITING

When it's time to get visual, the AudioFrame is clearly optimised for film and dialogue work. Sections of audio can be cut and placed in 'trim bins', where the audio is shown vertically, just like hanging up strips of film. Cut, paste, copy, and zoom in/out are supported; more esoteric features, like Alchemy's ability to translate sample rates and swap samples between different machines, are not. The visual editing capabilities are functional and easy to use (finding good loops is a cinch, probably owing to the interpolated samples that help you find exact loop points with great ease), but the bells and whistles belong to the future.

"Far from being a gimmick, AudioFrame's SoundStore database is one of those brilliantly obvious solutions to a very perplexing problem."

Still, there's more to sampling than sound quality and visual editing - the loading and organisation of samples is very important, especially in a time-equals-money studio or post-production environment. Loading time becomes significant for pulling Megabytes worth of sound from disk; however, the AudioFrame now implements an absolutely marvellous feature called 'SoundStore', which transfers samples from 90 to 300 Megabyte hard disks directly to RAM via SCSI. (Up to three 300 Megabyte hard disks will fit in one rack.) I watched one of the initial tests load 1.5 minutes of audio in seven seconds - most impressive. This feature alone could save hours, if not days, over the course of a year's worth of work.

But the coup de grace is an associative database built into the SoundStore package. All sounds are identified by multiple user-definable fields. For example, you could load all sounds used on a certain project, all sounds above a certain user-defined quality level, any sound that contains the word 'violin', etc.

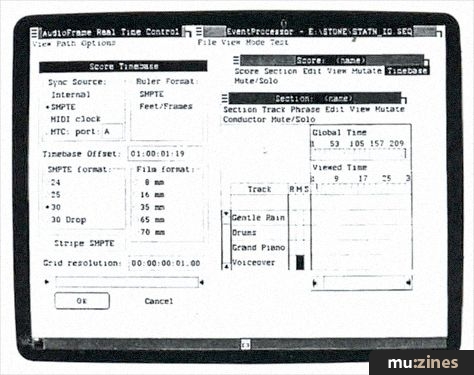

AudioFrame's EventProcessor sequencing software synchronises music and sound effects to a wide variety of external devices.

If you've ever tried to organise your samples, you know how hard it is to keep everything under control. Far from being a gimmick, AudioFrame's SoundStore database is one of those brilliantly obvious solutions to a very perplexing problem. (In fact, this inspired me to start cataloguing my Emulator II and Ensoniq EPS samples in Microsoft's Works, which has drastically cut down the time it takes me to find samples.) Features such as this, and the 'spreadsheet' of sample data that shows up on-screen, greatly speed the production process.

I tried storing video editing cues and syncing them to a Three Stooges movie; being able to read VITC directly (you just feed it into a BNC connector on the back) is a blessing, since you don't have to cue edit points 'on the fly'. I've never had the opportunity to use VITC before, but it's clearly an essential option for video work. When you have the appropriate edit point, click on the effect you want, and it's stored in the edit list, with 1/100th of a frame resolution.

THE SEQUENCER

AudioFrame's sequencer is very primitive. Considering it co-exists with features like SoundStore, the sequencer's lack of sophistication stands out all the more. To be fair, it makes more sense to spend precious engineering time on developing unique features; after all, you can use a standard MIDI sequencer to drive all those gorgeous sampled sounds. Still, that grates conceptually - after all, the AudioFrame is supposed to be a one-stop workstation.

"When you buy into a software-based system, you in effect marry a company. WaveFrame has not had much time to build a track record, but that track record is still undeniably impressive."

What we do have is 64 multi-channel tracks with quantisation, and the ability to assign separate tracks to separate channels (a la MIDIPaint + Jambox combination, which is great if you want to drive the internal samples and external MIDI devices without perceptible MIDI data clogging). And that's it - no punch-in or out, no overdubbing, no graphic editing, no event editing (although punches are scheduled for implementation, and in fact may already be available). To remedy this deficiency, Magnetic Music's Texture sequencer has been ported over to the AudioFrame, and it's not inconceivable that ports of other sequencers could become available. For now, though, the sequencer is best thought of as a tape recorder without razor blades. At least you can record different sections of a part on different tracks, so you don't have to redo an entire part every time you make one little mistake.

Eventually, I expect that the sequencer will be used more often than not in conjunction with the mixer. The mixer is great: 16 channels of digital audio (internal sampled sounds, or external audio sources hitting the A/D boards in real time), with input trim, four-band EQ with two parametric stages, four effects sends, sub-grouping, etc - all displayed in high resolution with a picture of a mixer. Click on a button, move the mouse, and voila! - the change is made. It's clean, quiet, and gives you a way to easily automate mixes, right down to EQ and pan changes.

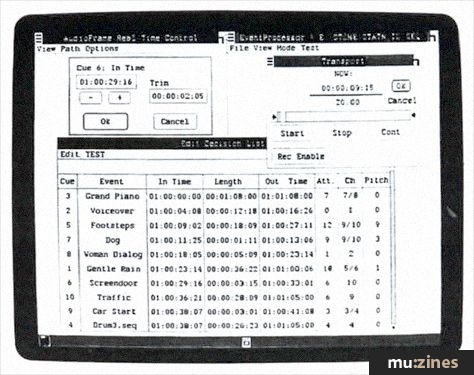

The Edit Decision List allows precise placement of effects and instrument sounds to SMPTE sub-frame accuracy.

One limitation is that using a mouse to adjust parameters puts you back in that change-one-parameter-at-a-time situation we all know and loathe. Fortunately, WaveFrame has started work on an improved user interface that will most likely use motorised faders. I suspect that the mixer is only a few updates away from being the digital mixer of my dreams. Meanwhile, because the mixer uses standard MIDI commands, I understand that several AudioFrame users are using J.L Cooper's MIDImation system strictly as a controller (audio, of course, is still routed through the AudioFrame, not the Cooper system). And what about the "but MIDI's too slow to control a mixer" argument? Well, don't forget that MIDI signals are running around inside the AudioFrame on a 1 Megabit per second bus - that's about 30 times the normal rate.

CONCLUSIONS

We need to consider two elements: what the AudioFrame can do right now, and its potential for the future. If you take any single element of the AudioFrame (except for sound quality, which is beyond reproach), there are products out there already that (arguably) do the job better. There are more sophisticated automation systems, and better (though not necessarily faster) dedicated visual editing programs. There are more expressive samplers out there, too. However, the AudioFrame combines a bunch of disparate elements in an ergonomic, intelligently-designed package with a level of integration and speed that could never be achieved with stand-alone products. Take the SoundStore, for example; adding in a database, while not a trivial job, was accomplished in a relatively short period of time and, thanks to the system integration, fits the sampling section like a glove. Basing the system on a Token Ring network is also wonderful; several users can access one master sound library, for example. And speaking of sound libraries, a collection of several hundred high quality sounds already exists, and more are on the way.

Of course, the big question is how the AudioFrame compares to a Synclavier or Fairlight. The Synclavier is a mature system that offers a lot right now. The Fairlight occupies a similar position. WaveFrame is the new kid on the block, and they have accomplished much in a very short period of time. But while no one would say the sequencer and mixer are unfinished - they do work and don't crash - they have yet to reach their full potential. How long it will take to reach that potential is anyone's guess, particularly since the potential is so vast... which brings us to the future.

When you buy into a software-based system, you in effect marry a company. WaveFrame has not had much time to build a track record, but that track record is still undeniably impressive. They came out of nowhere, hired top-notch talent, and have delivered on their promises to a degree that all but the most picky would consider exemplary. The design decisions behind the AudioFrame allow for a degree of expansion that should, in my opinion, give users about a six to 10 year ride (at the very least) on the cutting edge of technology. I expect that most AudioFrames will have paid back their owner's investment long before then, and the investment required by an AudioFrame is pretty reasonable, given the state of the art.

The bottom line? If you're in the market for a digital audio workstation, the AudioFrame is worth a very close look. For dialogue and video work, it's pretty exceptional right now. As a musical instrument, the sound quality is flawless; if WaveFrame can build in a bit more expressiveness, it will be unbeatable. The mixer is already brilliant; updates will only make it more compelling. And WaveFrame is just starting to learn how to use the DSP board to model acoustic sound sources. While full implementation of this feature is way off in the future (WaveFrame was reluctant for me to even mention it, since they don't want to be accused of luring customers with vapourware - but hey, I said it, not them), this could add a new dimension to the creation of synthetic sound.

Gambling on the future of a hi-tech company in an industry as fickle as the music business is always risky, but WaveFrame has proven that they have solid engineering/musical skills and a strong commitment to their product line. They're on to something, and they're on to something big.

FURTHER INFORMATION

Syco, (Contact Details).

© 1989 Mix magazine and reprinted with the kind permission of the publishers.

Publisher: Sound On Sound - SOS Publications Ltd.

The contents of this magazine are re-published here with the kind permission of SOS Publications Ltd.

The current copyright owner/s of this content may differ from the originally published copyright notice.

More details on copyright ownership...

Gear in this article:

Review by Craig Anderton

Help Support The Things You Love

mu:zines is the result of thousands of hours of effort, and will require many thousands more going forward to reach our goals of getting all this content online.

If you value this resource, you can support this project - it really helps!

Donations for January 2026

Issues donated this month: 0

New issues that have been donated or scanned for us this month.

Funds donated this month: £0.00

All donations and support are gratefully appreciated - thank you.

Magazines Needed - Can You Help?

Do you have any of these magazine issues?

If so, and you can donate, lend or scan them to help complete our archive, please get in touch via the Contribute page - thanks!