Magazine Archive

Home -> Magazines -> Issues -> Articles in this issue -> View

Passport Master Tracks Pro | |

A MIDI Control Program for the MacintoshArticle from Sound On Sound, October 1987 | |

Passport were one of the first US companies to offer music software for any computer. Richard Elen wades through the extensive features offered by their first music software release for the Apple Macintosh - a MIDI control program called Master Tracks Pro.

Richard Elen wades through the extensive features offered by Passport's first music software release for the Apple Macintosh.

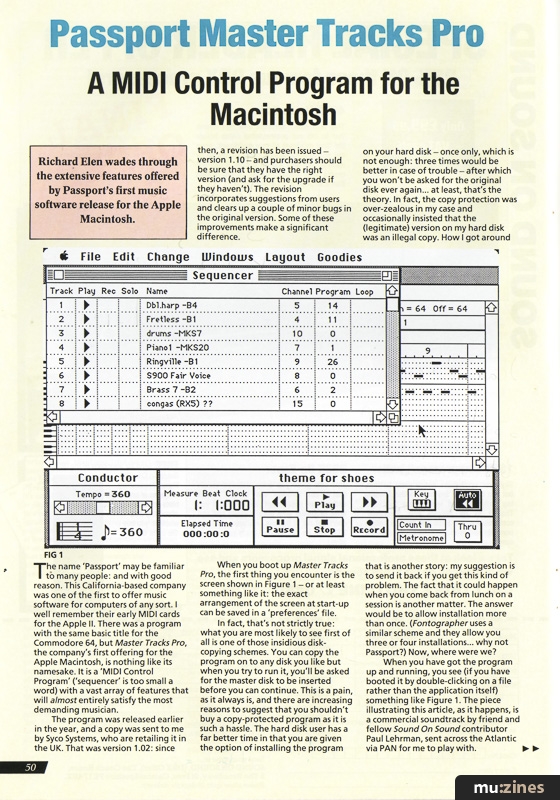

FIG 1

The name 'Passport' may be familiar to many people: and with good reason. This California-based company was one of the first to offer music software for computers of any sort. I well remember their early MIDI cards for the Apple II. There was a program with the same basic title for the Commodore 64, but Master Tracks Pro, the company's first offering for the Apple Macintosh, is nothing like its namesake. It is a 'MIDI Control Program' ('sequencer' is too small a word) with a vast array of features that will almost entirely satisfy the most demanding musician.

The program was released earlier in the year, and a copy was sent to me by Syco Systems, who are retailing it in the UK. That was version 1.02: since then, a revision has been issued - version 1.10 - and purchasers should be sure that they have the right version (and ask for the upgrade if they haven't). The revision incorporates suggestions from users and clears up a couple of minor bugs in the original version. Some of these improvements make a significant difference.

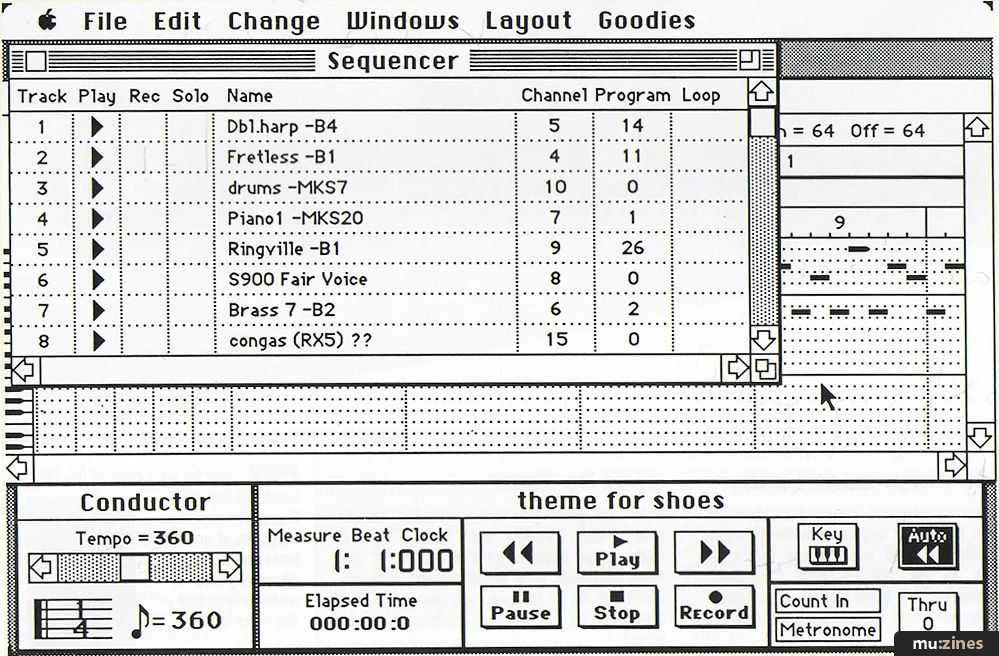

When you boot up Master Tracks Pro, the first thing you encounter is the screen shown in Figure 1 - or at least something like it: the exact arrangement of the screen at start-up can be saved in a 'preferences' file.

In fact, that's not strictly true: what you are most likely to see first of all is one of those insidious disk-copying schemes. You can copy the program on to any disk you like but when you try to run it, you'll be asked for the master disk to be inserted before you can continue. This is a pain, as it always is, and there are increasing reasons to suggest that you shouldn't buy a copy-protected program as it is such a hassle. The hard disk user has a far better time in that you are given the option of installing the program on your hard disk - once only, which is not enough: three times would be better in case of trouble - after which you won't be asked for the original disk ever again... at least, that's the theory. In fact, the copy protection was over-zealous in my case and occasionally insisted that the (legitimate) version on my hard disk was an illegal copy. How I got around that is another story: my suggestion is to send it back if you get this kind of problem. The fact that it could happen when you come back from lunch on a session is another matter. The answer would be to allow installation more than once. (Fontographer uses a similar scheme and they allow you three or four installations... why not Passport?) Now, where were we?

When you have got the program up and running, you see (if you have booted it by double-clicking on a file rather than the application itself) something like Figure 1. The piece illustrating this article, as it happens, is a commercial soundtrack by friend and fellow Sound On Sound contributor Paul Lehrman, sent across the Atlantic via PAN for me to play with.

The first thing to notice - looking at the Sequencer window - is that 'tracks' and 'channels' are not the same thing, as they are in some other programs. Here, Master Tracks remotely resembles Steinberg's Pro-24... with the exception that there are 64 tracks, and each track can contain data to be output on any MIDI channel - or every channel. A given track can be routed to a specified MIDI channel by clicking in the Channel box and entering a MIDI channel number in the miniature dialog box that appears, or you can enter '0' and have the track replay on whatever channels data was recorded on. Alternatively, you can record several tracks of different information - say a regular drum part on one track and fills on another - and route them to the same MIDI channel.

And to record on a track, simply click in the Record box and off you go. Unlike some systems, the default record mode is to erase what was previously on a track - in other words, like a tape machine. And while recording you can filter out unwanted MIDI data if you wish.

The remaining two areas in the Sequencer window - apart from the obvious place where you can input the names of instruments - are Program and Loop. The former determines the patch number - if any - that's sent to the destination channel when a piece is played, while 'Loop' simply does what it says: it loops the track. In this case a small 'return' symbol appears in the window.

A natural place to examine next is the Transport window (bottom right in Figure 1) where the title of the piece is displayed above a pretty normal set of transport controls (all of which can be selected from the music keyboard, incidentally) and a pair of indicators to tell you where you are - in both measures (bars), beats and clock pulses (240 clocks per crotchet is the resolution here: a very good figure) and in minutes/seconds/tenths. Having both is very useful, and I'm very used to it because my own sequencer does that, but many do not.

To the right of the transport controls are five more buttons. Selecting the 'Key' icon, by clicking on it, means that the program will wait until you play a note on a connected MIDI keyboard before going into play or record: another valuable feature that is not offered by everyone.

Auto << is essentially an automatic rewind function: when you stop the music, it goes back to the top if this icon is highlighted.

Selecting the 'Thru' box brings up the familiar mini-dialog box enabling you to enter a number. If you leave it set at 0, data will be echoed through the program on the channel it comes in on - unless you have selected Record on a track, in which case data will be echoed on the channel to which that track is assigned. The latter is a vital feature (otherwise you need to do far too many things when you want to record) which has been added in the latest version thanks to user feedback.

Count In and Metronome are relatively self-explanatory: the former gives you a single bar intro (a bar being defined in the Conductor section of the program), while the metronome is a rather less nasty click from the Macintosh computer's internal speaker than most people's. In the niggles department, you should really be able to define the number of bars count-in, and the metronome should be capable of being routed to a specified MIDI note value and channel (ie. the rimshot on my drum machine), as relying on the internal speaker is only OK if you are recording very quiet music.

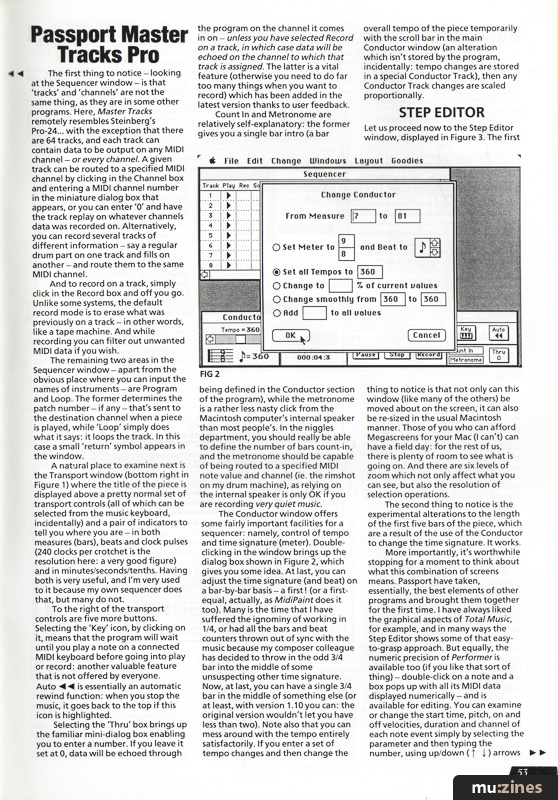

FIG 2

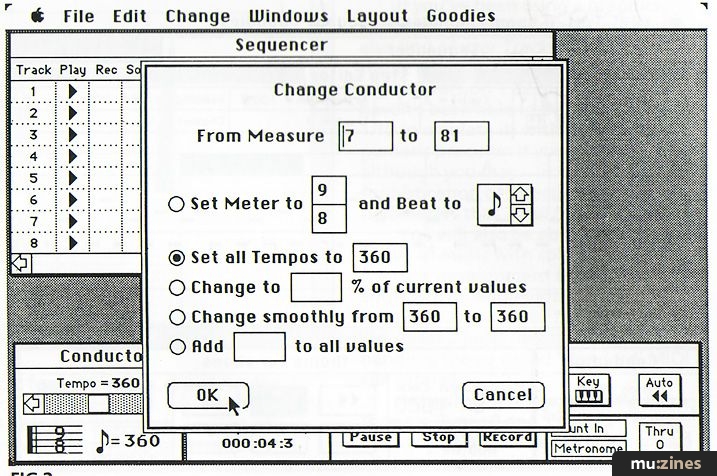

The Conductor window offers some fairly important facilities for a sequencer: namely, control of tempo and time signature (meter). Double-clicking in the window brings up the dialog box shown in Figure 2, which gives you some idea. At last, you can adjust the time signature (and beat) on a bar-by-bar basis - a first! (or a first-equal, actually, as MidiPaint does it too). Many is the time that I have suffered the ignominy of working in 1/4, or had all the bars and beat counters thrown out of sync with the music because my composer colleague has decided to throw in the odd 3/4 bar into the middle of some unsuspecting other time signature. Now, at last, you can have a single 3/4 bar in the middle of something else (or at least, with version 1.10 you can: the original version wouldn't let you have less than two). Note also that you can mess around with the tempo entirely satisfactorily. If you enter a set of tempo changes and then change the overall tempo of the piece temporarily with the scroll bar in the main Conductor window (an alteration which isn't stored by the program, incidentally: tempo changes are stored in a special Conductor Track), then any Conductor Track changes are scaled proportionally.

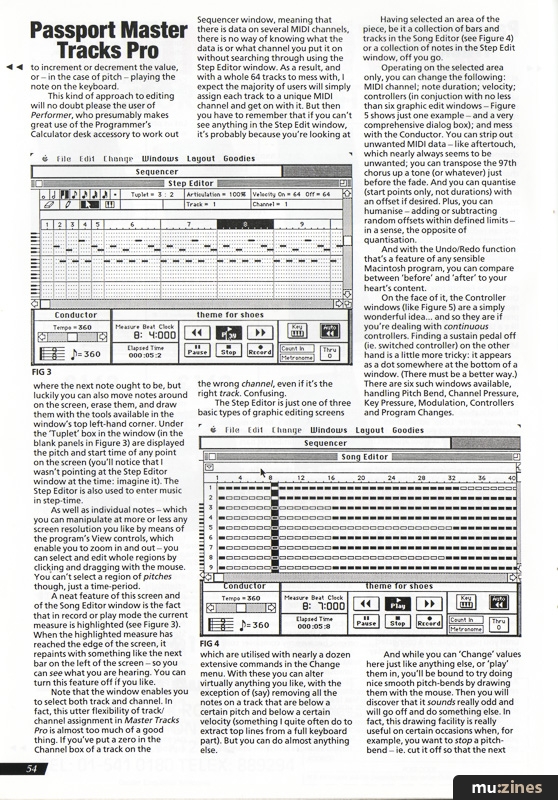

FIG 3

STEP EDITOR

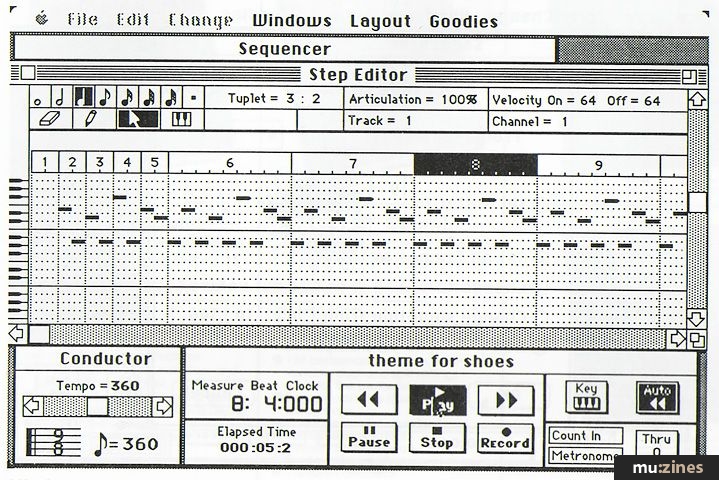

Let us proceed now to the Step Editor window, displayed in Figure 3. The first thing to notice is that not only can this window (like many of the others) be moved about on the screen, it can also be re-sized in the usual Macintosh manner. Those of you who can afford Megascreens for your Mac (I can't) can have a field day: for the rest of us, there is plenty of room to see what is going on. And there are six levels of zoom which not only affect what you can see, but also the resolution of selection operations.

The second thing to notice is the experimental alterations to the length of the first five bars of the piece, which are a result of the use of the Conductor to change the time signature. It works.

More importantly, it's worthwhile stopping for a moment to think about what this combination of screens means. Passport have taken, essentially, the best elements of other programs and brought them together for the first time. I have always liked the graphical aspects of Total Music, for example, and in many ways the Step Editor shows some of that easy-to-grasp approach. But equally, the numeric precision of Performer is available too (if you like that sort of thing) - double-click on a note and a box pops up with all its MIDI data displayed numerically - and is available for editing. You can examine or change the start time, pitch, on and off velocities, duration and channel of each note event simply by selecting the parameter and then typing the number, using up/down arrows to increment or decrement the value, or - in the case of pitch - playing the note on the keyboard.

This kind of approach to editing will no doubt please the user of Performer, who presumably makes great use of the Programmer's Calculator desk accessory to work out where the next note ought to be, but luckily you can also move notes around on the screen, erase them, and draw them with the tools available in the window's top left-hand corner. Under the 'Tuplet' box in the window (in the blank panels in Figure 3) are displayed the pitch and start time of any point on the screen (you'll notice that I wasn't pointing at the Step Editor window at the time: imagine it). The Step Editor is also used to enter music in step-time.

As well as individual notes - which you can manipulate at more or less any screen resolution you like by means of the program's View controls, which enable you to zoom in and out - you can select and edit whole regions by clicking and dragging with the mouse. You can't select a region of pitches though, just a time-period.

A neat feature of this screen and of the Song Editor window is the fact that in record or play mode the current measure is highlighted (see Figure 3). When the highlighted measure has reached the edge of the screen, it repaints with something like the next bar on the left of the screen - so you can see what you are hearing. You can turn this feature off if you like.

Note that the window enables you to select both track and channel. In fact, this utter flexibility of track/channel assignment in Master Tracks Pro is almost too much of a good thing. If you've put a zero in the Channel box of a track on the Sequencer window, meaning that there is data on several MIDI channels, there is no way of knowing what the data is or what channel you put it on without searching through using the Step Editor window. As a result, and with a whole 64 tracks to mess with, I expect the majority of users will simply assign each track to a unique MIDI channel and get on with it. But then you have to remember that if you can't see anything in the Step Edit window, it's probably because you're looking at the wrong channel, even if it's the right track. Confusing.

The Step Editor is just one of three basic types of graphic editing screens which are utilised with nearly a dozen extensive commands in the Change menu. With these you can alter virtually anything you like, with the exception of (say) removing all the notes on a track that are below a certain pitch and below a certain velocity (something I quite often do to extract top lines from a full keyboard part). But you can do almost anything else.

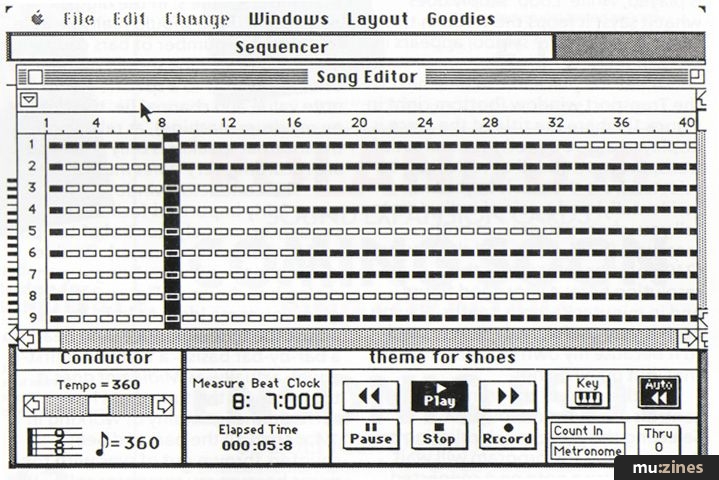

Having selected an area of the piece, be it a collection of bars and tracks in the Song Editor (see Figure 4) or a collection of notes in the Step Edit window, off you go.

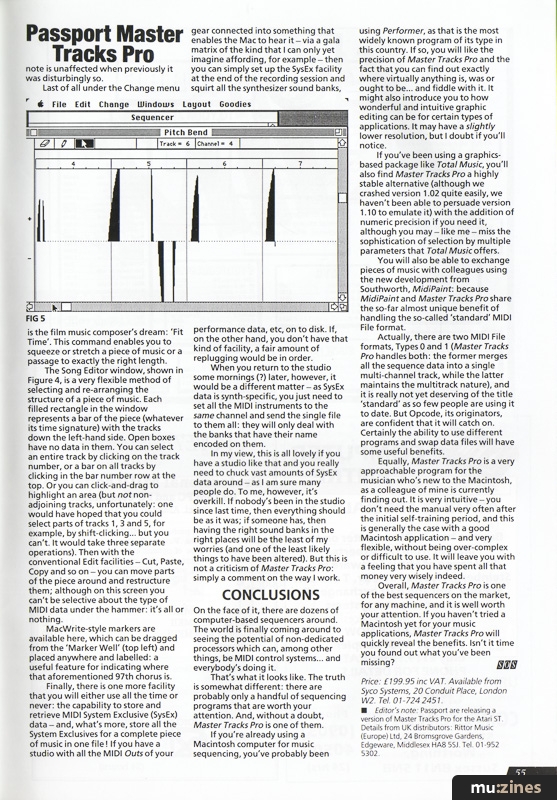

FIG 4

Operating on the selected area only, you can change the following: MIDI channel; note duration; velocity; controllers (in conjunction with no less than six graphic edit windows - Figure 5 shows just one example - and a very comprehensive dialog box); and mess with the Conductor. You can strip out unwanted MIDI data - like aftertouch, which nearly always seems to be unwanted; you can transpose the 97th chorus up a tone (or whatever) just before the fade. And you can quantise (start points only, not durations) with an offset if desired. Plus, you can humanise - adding or subtracting random offsets within defined limits - in a sense, the opposite of quantisation.

And with the Undo/Redo function that's a feature of any sensible Macintosh program, you can compare between 'before' and 'after' to your heart's content.

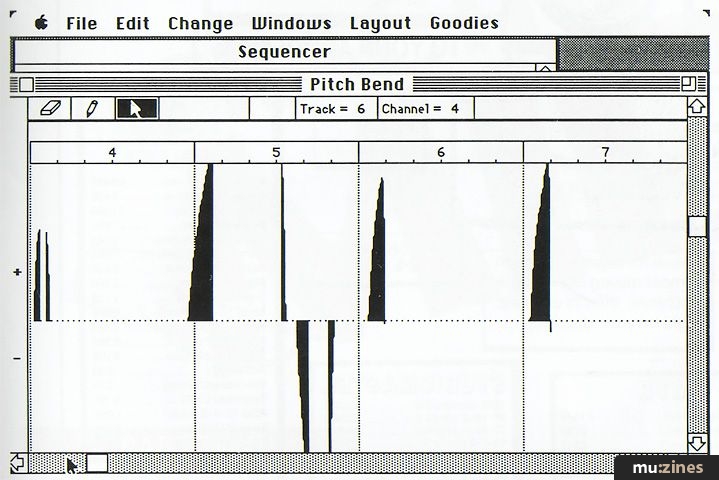

On the face of it, the Controller windows (like Figure 5) are a simply wonderful idea... and so they are if you're dealing with continuous controllers. Finding a sustain pedal off (ie. switched controller) on the other hand is a little more tricky: it appears as a dot somewhere at the bottom of a window. (There must be a better way.) There are six such windows available, handling Pitch Bend, Channel Pressure, Key Pressure, Modulation, Controllers and Program Changes.

FIG 5

And while you can 'Change' values here just like anything else, or 'play' them in, you'll be bound to try doing nice smooth pitch-bends by drawing them with the mouse. Then you will discover that it sounds really odd and will go off and do something else. In fact, this drawing facility is really useful on certain occasions when, for example, you want to stop a pitch-bend - ie. cut it off so that the next note is unaffected when previously it was disturbingly so.

Last of all under the Change menu is the film music composer's dream: 'Fit Time'. This command enables you to squeeze or stretch a piece of music or a passage to exactly the right length.

The Song Editor window, shown in Figure 4, is a very flexible method of selecting and re-arranging the structure of a piece of music. Each filled rectangle in the window represents a bar of the piece (whatever its time signature) with the tracks down the left-hand side. Open boxes have no data in them. You can select an entire track by clicking on the track number, or a bar on all tracks by clicking in the bar number row at the top. Or you can click-and-drag to highlight an area (but not non-adjoining tracks, unfortunately: one would have hoped that you could select parts of tracks 1, 3 and 5, for example, by shift-clicking... but you can't. It would take three separate operations). Then with the conventional Edit facilities - Cut, Paste, Copy and so on - you can move parts of the piece around and restructure them; although on this screen you can't be selective about the type of MIDI data under the hammer: it's all or nothing.

MacWrite-style markers are available here, which can be dragged from the 'Marker Well' (top left) and placed anywhere and labelled: a useful feature for indicating where that aforementioned 97th chorus is.

Finally, there is one more facility that you will either use all the time or never: the capability to store and retrieve MIDI System Exclusive (SysEx) data - and, what's more, store all the System Exclusives for a complete piece of music in one file! If you have a studio with all the MIDI Outs of your gear connected into something that enables the Mac to hear it - via a gala matrix of the kind that I can only yet imagine affording, for example - then you can simply set up the SysEx facility at the end of the recording session and squirt all the synthesizer sound banks, performance data, etc, on to disk. If, on the other hand, you don't have that kind of facility, a fair amount of replugging would be in order.

When you return to the studio some mornings (?) later, however, it would be a different matter - as SysEx data is synth-specific, you just need to set all the MIDI instruments to the same channel and send the single file to them all: they will only deal with the banks that have their name encoded on them.

In my view, this is all lovely if you have a studio like that and you really need to chuck vast amounts of SysEx data around - as I am sure many people do. To me, however, it's overkill. If nobody's been in the studio since last time, then everything should be as it was; if someone has, then having the right sound banks in the right places will be the least of my worries (and one of the least likely things to have been altered). But this is not a criticism of Master Tracks Pro: simply a comment on the way I work.

CONCLUSIONS

On the face of it, there are dozens of computer-based sequencers around. The world is finally coming around to seeing the potential of non-dedicated processors which can, among other things, be MIDI control systems... and everybody's doing it.

That's what it looks like. The truth is somewhat different: there are probably only a handful of sequencing programs that are worth your attention. And, without a doubt, Master Tracks Pro is one of them.

If you're already using a Macintosh computer for music sequencing, you've probably been using Performer, as that is the most widely known program of its type in this country. If so, you will like the precision of Master Tracks Pro and the fact that you can find out exactly where virtually anything is, was or ought to be... and fiddle with it. It might also introduce you to how wonderful and intuitive graphic editing can be for certain types of applications. It may have a slightly lower resolution, but I doubt if you'll notice.

If you've been using a graphics-based package like Total Music, you'll also find Master Tracks Pro a highly stable alternative (although we crashed version 1.02 quite easily, we haven't been able to persuade version 1.10 to emulate it) with the addition of numeric precision if you need it, although you may - like me - miss the sophistication of selection by multiple parameters that Total Music offers.

You will also be able to exchange pieces of music with colleagues using the new development from Southworth, MidiPaint: because MidiPaint and Master Tracks Pro share the so-far almost unique benefit of handling the so-called 'standard' MIDI File format.

Actually, there are two MIDI File formats, Types 0 and 1 (Master Tracks Pro handles both: the former merges all the sequence data into a single multi-channel track, while the latter maintains the multitrack nature), and it is really not yet deserving of the title 'standard' as so few people are using it to date. But Opcode, its originators, are confident that it will catch on. Certainly the ability to use different programs and swap data files will have some useful benefits.

Equally, Master Tracks Pro is a very approachable program for the musician who's new to the Macintosh, as a colleague of mine is currently finding out. It is very intuitive - you don't need the manual very often after the initial self-training period, and this is generally the case with a good Macintosh application - and very flexible, without being over-complex or difficult to use. It will leave you with a feeling that you have spent all that money very wisely indeed.

Overall, Master Tracks Pro is one of the best sequencers on the market, for any machine, and it is well worth your attention. If you haven't tried a Macintosh yet for your music applications, Master Tracks Pro will quickly reveal the benefits. Isn't it time you found out what you've been missing?

Price : £199.95 inc VAT.

Available from Syco Systems, (Contact Details).

Editor's note: Passport are releasing a version of Master Tracks Pro for the Atari ST. Details from UK distributors: Rittor Music (Europe) Ltd, (Contact Details).

Also featuring gear in this article

Master or Servant

(MIC Apr 89)

Master Tracks Pro

(MIC Feb 90)

Master Tracks Pro 5 - Mac Sequencing Software

(SOS Jul 92)

Passport Master Tracks Pro 4.5.3

(SOS Oct 91)

Passport Mastertracks Pro

(MT Sep 90)

Browse category: Software: Sequencer/DAW > Passport Designs

Featuring related gear

Making Tracks - Passport Master Tracks Junior

(SOS Sep 88)

Browse category: Software: Sequencer/DAW > Passport Designs

Publisher: Sound On Sound - SOS Publications Ltd.

The contents of this magazine are re-published here with the kind permission of SOS Publications Ltd.

The current copyright owner/s of this content may differ from the originally published copyright notice.

More details on copyright ownership...

Review by Richard Elen

Help Support The Things You Love

mu:zines is the result of thousands of hours of effort, and will require many thousands more going forward to reach our goals of getting all this content online.

If you value this resource, you can support this project - it really helps!

Donations for November 2025

Issues donated this month: 0

New issues that have been donated or scanned for us this month.

Funds donated this month: £0.00

All donations and support are gratefully appreciated - thank you.

Magazines Needed - Can You Help?

Do you have any of these magazine issues?

If so, and you can donate, lend or scan them to help complete our archive, please get in touch via the Contribute page - thanks!