Magazine Archive

Home -> Magazines -> Issues -> Articles in this issue -> View

On The Beat (Part 2) | |

Article from Music Technology, September 1989 | |

The second part in this series on drum machine programming concentrates on the use of the hi-hat. Nigel Lord looks at its role in humanising your drum patterns.

IN THE SECOND PART OF THIS SERIES ON RHYTHM PROGRAMMING, WE EXAMINE THE IMPORTANCE OF THE HI-HAT.

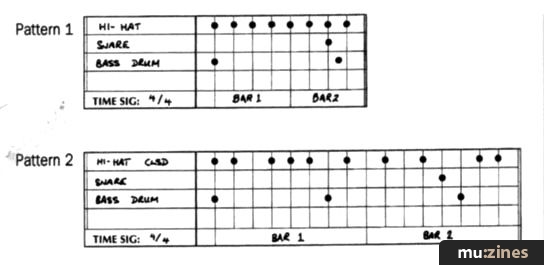

SORRY TO BE apologising for mistakes so early in the series, but in my introductory article last month, the snare and bass drum notes managed to find their way onto the wrong beats of bar two in pattern nine (the penultimate pattern). The placing of the snare drum should have been the same as in pattern eight and ten, but for some reason it ended up a beat early and this brought the bass drum forward as well. If you followed the text, you would probably have spotted the error, as no mention was made of the snare beat being moved. To avoid any further confusion, however, the pattern is repeated as Pattern 1.

Actually, reprinting this pattern has proved quite fortuitous, as it represents an excellent starting point for the examples in this month's article. Here we shall attempt to extend the role of the hi-hat.

Having programed many different styles on a wide variety of machines over the years, it is my belief that the battle to produce natural, fluid-sounding rhythms is often won or lost on the hi-hat line of the pattern grid. Actually, I must expand on this to include any instrument which acts as a metronome within the bar; it just happens that, in conventional programming, this task usually falls to the closed hi-hat. For some reason most people - even quite experienced programmers - are quite happy to let the hi-hat tick away without ever thinking of putting a little extra programming time into accenting or displacing any of the beats.

I suspect that this is connected with the hi-hat's traditional role as a time-keeper: using it as the pulse against which everything else is positioned in the bar.

It's all too easy to simply forget that it is an instrument in its own right and deserves to be treated as such - in most forms of music, at least. As I've already pointed out, if you're hoping to produce natural-sounding rhythm tracks (I've purposely avoided using the expression "reaI-sounding"), how you put together the hi-hat part will prove critical to its ultimate success or failure.

Besides doubling up the number of closed hi-hat beats in the bar - from four to eight, or eight to 16 (or, of course, halving them) - the simplest way of adding a little colour to the hi-hat track is by removing a few of the beats altogether. Taking out the beats which coincide with the snare drum, for example, doesn't detract from the overall feel of a pattern (it's often scarcely detectable, given the overlapping sound frequencies often involved), yet it can go some way to alleviating the monotony of a constant eight- or 16-to-the-bar tick.

Beyond this, unless you're specifically trying to achieve a machine-like feel to your rhythm, listening to a pattern and dispensing with all those hi-hat beats which aren't absolutely necessary has a lot to recommend it. Somehow the absence of any tonal variation in a hi-hat voice (whether electronically generated or sampled), is not nearly as noticeable if a little space is introduced between certain notes. In other words, if it is syncopated.

But of course, that's only part of the story. Inserting notes - particularly those which occur on what could be termed offbeats - can be equally productive, particularly where space has been created by the deletion of more predictable' events. And dynamics, too, play a significant role in the syncopation of the hi-hat - more sophisticated drum machines allowing the programming of quite compelling rhythmic figures. But we're getting ahead of ourselves. Let's start with last month's rogue pattern and introduce a little spice to the hi-hat line. (See Pattern 2)

As you will notice, the increased hi-hat activity has necessitated the change to eight beats to the bar for the grid. (The pattern can be programmed as four bars of 4/4 and the tempo increased if this makes life easier for you, but remember that this will mean that the rest of your song will run at double time if you're using a sequencer sync'd to your drum machine via MIDI.) Loading the new pattern into your machine, you'll notice that the whole feel of the rhythm has been transformed despite the fact that the snare and bass drum beats are in exactly the same place.

Moving the hi-hat beats around at the beginning of bar one brings about a subtle, yet quite definite, change and a jazzier feel. (See Pattern 3)

To achieve this, it has been necessary to introduce a degree of dynamic programming to the proceedings, but in line with our intention to keep the series relevant to those with more modest drum machines, this amounts to no more than accenting certain beats.

From here it's simply a matter of further rearranging the hi-hat part to produce variations on the basic rhythmic feel again using accented notes. (See Patterns 4 and 5)

Maintaining the position of the bass and snare drums whilst changing the feel of the hi-hat in this way provides an effective approach to programming an entire song. A degree of consistency is preserved throughout the patterns, yet there is sufficient variation to reflect the differing feel of individual song sections. The number of possible combinations is vast - even limiting yourself to the 16 beats and two dynamic levels these patterns are based on. But this will be tempered by the need to tie in with other rhythmic elements in the song - this is particularly true if some of those elements have already been written.

In the following pattern, one of the most common (some would say predictable) snare/bass drum grooves is given a new lease of life by programming a few accents on the hi-hat... (See Pattern 6)

As you will hear, even with the same number of beats per bar as the standard rhythm, the accents lend the pattern a sense of urgency which lifts it above the mundane.

For something rather more striking, you could try programming in a couple of extra beats between beats 1 & 2 and 2 & 3. This will mean doubling the resolution to accommodate 32nd notes (and reprogramming the snare and bass if each instrument cannot be individually quantised), but even the most humble drum machine should be able to resolve to this level. Incidentally, the accent on the first note is included to improve the definition of the opening figure. (See Pattern 7)

Using patterns 6 and 7 in combination should also prove worthwhile, particularly if the 32nd notes of the second pattern are programmed to occur at strategic points in a song.

For something a little less upfront, try replacing the hi-hat part with that in Pattern 8.

Even though programming is still restricted to accented and non-accented beats, the hi-hat is syncopated in a subtle and pleasantly insistent way which compliments the bass/snare combination. The light and shade created by the accents produces an echo-like effect on certain beats - and increases the foot-tapping quotient considerably (I don't know the correct technical term for this, I'm afraid). Obviously those with drum machines capable of greater dynamic sophistication will see opportunities here for further experimentation, but even in its basic form, the pattern has considerable potential across a wide range of styles.

Putting aside my personal dislike of the open hi-hat on practically every drum machine I've come across, it is, perhaps, time we looked at the rhythmic possibilities of the two hi-hat sounds in combination. In many situations an open hi-hat may be freely exchanged for an accented closed hi-hat. And it may well prove interesting making the necessary program changes to accommodate this in some of the patterns here. It should be remembered, though, that an open hi-hat left hanging (so to speak) is not a very attractive sound. As a general rule it is better to close an open hat down as soon as is rhythmically possible.

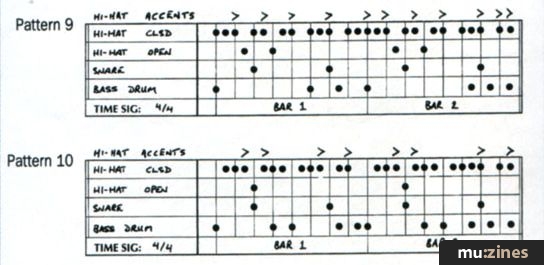

The following two dance patterns make use of the open hi-hat to add rhythmic interest and, again, having broadly similar feels, they could be adapted for use in the same song. (See Patterns 9 and 10)

Unlike drum voices, some quite elaborate hi-hat figures can be programmed without the danger of them becoming intrusive. This next example makes use of both open and closed voices to produce the kind of fill normally associated with real drummers (and good ones at that). But although it sounds quite complex, we're still only using the hi-hat, snare and bass drum voices, and two levels of dynamics. (See Pattern 11)

Finally this month, an example of a simple rhythm given added interest by shifting the hi-hat onto the off-beat. This pattern, too, makes a good starting point for experimentation. (See Pattern 12)

Writing a rhythm pattern is clearly an interactive process - both in terms of its relationship with the rest of the song, and the relationship of the individual instruments within the pattern. Thus, after we've re-written the hi-hat part and changed the feel of the rhythm, there's nothing to stop us taking a further look at the other instruments and deciding whether these could now be improved upon. Like so many things, producing the right groove for a piece of music takes time and patience, and should always be seen as more than an exercise in time-keeping.

Series - "On The Beat"

Read the next part in this series:

On The Beat (Part 3)

(MT Oct 89)

All parts in this series:

Part 1 | Part 2 (Viewing) | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8 | Part 9 | Part 10 | Part 11 | Part 12 | Part 13 | Part 14 | Part 15 | Part 16 | Part 17 | Part 18 | Part 19 | Part 20 | Part 21 | Part 22 | Part 23 | Part 24 | Part 25 | Part 26 | Part 26 | Part 27 | Part 28 | Part 29 | Part 30 | Part 31 | Part 32 | Part 33 | Part 34 | Part 35

More with this topic

Rhythm and Fuse |

Personalise Your Drum Machine Sounds - Masterclass - Drum Machines |

Drum Programming - A Series By Warren Cann (Part 1) |

Funky Stuff - Making Classic Funk |

On The Beat - the next generation (Part 1) |

Beat Box |

Steal The Feel (Part 1) |

Beat Box |

The Rhythm Method - Beat Box Hits |

Warren Cann's Electro-Drum Column (Part 1) |

The Sounds Of Motown |

Off the Wall |

Browse by Topic:

Drum Programming

Publisher: Music Technology - Music Maker Publications (UK), Future Publishing.

The current copyright owner/s of this content may differ from the originally published copyright notice.

More details on copyright ownership...

Topic:

Drum Programming

Series:

On The Beat

Part 1 | Part 2 (Viewing) | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8 | Part 9 | Part 10 | Part 11 | Part 12 | Part 13 | Part 14 | Part 15 | Part 16 | Part 17 | Part 18 | Part 19 | Part 20 | Part 21 | Part 22 | Part 23 | Part 24 | Part 25 | Part 26 | Part 26 | Part 27 | Part 28 | Part 29 | Part 30 | Part 31 | Part 32 | Part 33 | Part 34 | Part 35

Feature by Nigel Lord

Help Support The Things You Love

mu:zines is the result of thousands of hours of effort, and will require many thousands more going forward to reach our goals of getting all this content online.

If you value this resource, you can support this project - it really helps!

Donations for April 2024

Issues donated this month: 0

New issues that have been donated or scanned for us this month.

Funds donated this month: £7.00

All donations and support are gratefully appreciated - thank you.

Magazines Needed - Can You Help?

Do you have any of these magazine issues?

If so, and you can donate, lend or scan them to help complete our archive, please get in touch via the Contribute page - thanks!