Magazine Archive

Home -> Magazines -> Issues -> Articles in this issue -> View

Article Group: | |

Audio additions | |

Steinberg Cubase Audio v2.0Article from The Mix, September 1994 | |

D-to-D meets MIDI - properly this time

The first version of Steinberg's Cubase Audio promised the seamless integration of MIDI sequencing with direct-to-disk recording - and pointedly failed to deliver. Nigel Lord checks out Version 2.0 for the Macintosh to find out if all the bugs have been sprayed with something nasty

The Audio Editor, where audio events may be cut up and freely moved around

We all screw up occasionally. Whether you're an Italian footballer taking the deciding penalty in the World Cup Final, or the chap in the pit lane at the German Grand Prix about to refuel Verstappen's car, the pressure is on and catastrophe lurks just around the corner. For most of us, there's only one chance to get it right.

Software writers are among the fortunate few exceptions. They occupy the rare position of being able to correct virtually any mistake through the release of upgrades. And where there's even the bonus of a few new features at no extra cost to existing users, it's actually possible to emerge from the whole exercise with some credit. On other occasions, though, people end up so naffed off with a particular piece of software that no amount of new features included in the upgrade can pacify them, and the manufacturer is left with a well-nigh unmarketable product.

If Cubase Audio v1.0 didn't actually descend to this level, it came perilously close. I bought my copy at a bargain price from a disgruntled studio owner who had apparently lost a number of important sessions. He'd gone back to using analogue tape.

The program seemed to take umbrage whenever the metronome click was switched on - which, given the fact that the default song automatically loaded with it switched on, meant it was quite some time before I got the thing up and running. When I did, the procession of bugs - both predictable and unpredictable - tripped me up repeatedly, often responding only to a complete restart of my Mac.

What seems like a thousand Macintosh restart 'chords' later, the long-awaited v2.0 of Cubase Audio is now with us - free to existing registered users, free from the tyranny of the dongle... and almost free of bugs. And, most importantly, capable of the kind of impressive results which were always promised from the marriage of a sophisticated direct-to-disk recording system with what is still Europe's leading MIDI sequencer.

The story so far

Essentially, Cubase Audio offers straightforward integration of recordable digital audio tracks and conventional MIDI tracks within a sequencer environment, which allows you to edit and playback both in similar ways. Not exactly similar, as we'll discover, but comparable to the extent that anyone familiar with MIDI sequencing should quickly feel at home.

There is virtually no limit to the number of audio tracks which may be recorded, though the number of channels through which these can be output is strictly limited by the hardware installed in your Mac. At the present time, Cubase Audio is wholly dependent on Digidesign hardware options (see side panel), which offer 2-16 channels of digital audio, according to the system. What this means in real terms is that you can have as many tracks of audio as you like in your arrangement, but in a four-channel system (for example), only four will sound simultaneously.

There are ways around this. You can mix audio from several tracks down to one (without losing individual track integrity - or quality) and then use the spare channels created to play back other tracks. And providing that the audio on various tracks doesn't coincide (as is often the case, musically) you aren't using up your full channel capacity anyway.

The Audio Pool - a complete directory of all your audio sound files and segments

System hierarchy

When you record a piece of music on one of Cubase's audio channels, the program creates a 'sound file' which it automatically saves to disk. This sound file does not have to be played in its entirety; smaller sections of the file - referred to as 'segments' - can be defined simply by marking their start and end positions within the sound file.

The Audio Pool, accessed from the Audio menu, contains a complete list of all sound files and their associated segments, together with extensive information about their position, duration, and so on. Segments or complete sound files can be dragged from here onto audio tracks within the Arrange page, where they become parts like any others.

Straightforward as this may seem, it's a bit of an inside-out view of things. Existing Cubase users will feel more comfortable when they learn that creating a sound file involves little more than selecting one of the audio tracks in the Arrange page and pressing Record. When recording is completed, you hit Stop and a part appears just as it does on a MIDI track, and can be moved around in exactly the same way. Cut the part up and you've instantly created a segment which, together with its associated sound file, will be automatically added to the Audio Pool and indexed with a small number to indicate how many times it has been used within an arrangement.

The purpose of this is to conserve disk space by simply 'flagging' the section of a sound file you wish to repeat, so that the computer knows what to replay, without duplicating all the data. The relationship between segments, the parts that appear on the Arrange page and the events they contain, is simply that each event within a part plays back one segment via one channel.

The Audio Pool acts as a distribution centre for your sound files and segments, where it's possible to determine exactly what you have in the system at any one time. It's also used as the reception point for previously recorded files being imported into an arrangement, and uses a neat dialogue box which allows you to audition files before loading them in.

One of the Audio Pool's other major functions is to remove background noise, clicks and so on from segments where this may be evident between sections of music. The oddly titled 'Banish Silence' facility doesn't actually banish silence - it creates it, rather like a noise gate, where everything below a predetermined threshold level is gated out. Misnomer or not, it works well and can prove indispensable when cleaning up sections of audio.

"I wouldn't work without the auto-save function switched on"

Audio editing

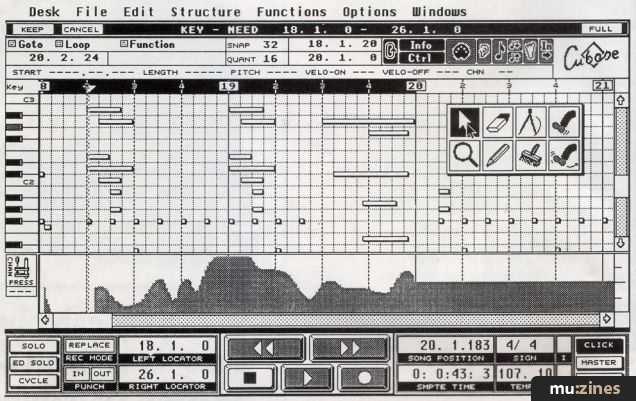

Manipulation of waveforms doesn't really begin in earnest until you enter the Audio Editor - which, like Cubase's other editors, comes replete with its own functions bar and its own set of tools.

What you're actually working on here are audio events displayed as boxes, which may or may not display a waveform (it's up to you). The length of a box represents the length of an event, and when highlighted also reveals its position - just as in the Arrange page. Note that a part (on which you double-click to enter the Audio Editor) need not be restricted to playing a single segment. Several segments may be laid out in parallel along what, in Cubase parlance, are known as 'lanes'.

Although Cubase Audio plays back only mono files, a grouping facility in the Audio Editor makes it possible to carry out simultaneous editing of two or more recordings as a single entity.

Because the beginning of an audio event (unlike a MIDI event) may well not occur at any musically significant position, each one is given a 'Q-point' which can be used for snapping it to the nearest quantise position. (The first downbeat in a segment would be an obvious example of a Q-point.) Segments dragged into an arrangement, or into the Audio Editor from the Audio Pool, have their destination positions determined by the Q-point, which may be entered automatically or manually.

The Wave Editor - serious waveform editing begins here

If you want to get destructive, then the Wave Editor is where you need to be. Here you can carry out direct editing of a waveform on your disk, to make permanent changes to the audio. This is also where the much-vaunted editing to 'sample-level accuracy' takes place, using the powerful magnification facilities offered by Cubase Audio.

Though all the standard cutting, copying and pasting procedures apply in the Wave Editor, it features a rather more interesting method of performing special tasks such as normalising (bringing low-level signals up to maximum output). The system relies on a series of 'plug-ins' - miniature computer programs designed to perform specific editing functions on your audio files. Third-party developers are being encouraged to produce their own range of plug-ins, and when this happens there ought to be a much broader palette of effects to choose from. It sounds a neat idea (it's already worked well with a number of Mac DTP packages - Ed) let's just hope it works out in practice.

Cubase Audio includes extensive EQ facilities. In addition to full parametric EQ with variable bandwidth control, you'll find low and high shelving filters, and low and high cut filters. Each EQ channel is given four user-defined presets so that you can quickly switch between different EQ setups.

The EQ and Monitor boxes, as displayed with a four-channel system

The upgrade path

Cubase Audio v2.0 is in every way a major revision of the original program, with a wealth of new features and improvements. Here are the edited highlights...

• The program now supports up to four channels on Audiomedia cards, eight channels on Session 8 systems, and up to 16 channels with Pro Tools.

• Full integration of Digidesign's Digital Audio Engine has been incorporated.

• Editing is now down to sample-level accuracy.

• Audio 'scrubbing' is now possible, as are real-time EQ control and audio track delay.

• Support for QuickTime movies is now included.

Individually these innovations may not seem too important, but collectively they go a long way toward making the program useful and useable in a serious programming and/or recording environment. There are dozens of smaller improvements, and in the nature of software development, more are doubtless already in the Steinberg pipeline.

"Cubase Audio now fulfils everything it promised - and then some"

Verdict

The best reason for buying a program like Cubase Audio is that it offers - at precisely the right point in the chain - full integration of MIDI and audio, and treats the two in similar ways. As a long-time Cubase user, I came to loathe the process of leaving behind the on-screen, highly visual world of recording MIDI data and moving into the rather closed environment of magnetic tape. I longed for the day I could treat audio information in the same way I was able to manipulate MIDI. With the advent of the new and much-improved Cubase Audio, that day has dawned. Cubase Audio now fulfils everything it promised - and then some. It's a quite superb program which builds on the success of Cubase the sequencer to the extent that the program has become one, seamless whole.

A few bugs are still in evidence, but nothing to lose sleep over. I wouldn't work without the auto-save function switched on, particularly in view of the speed with which a song is backed up to hard disk. But in almost two months' continuous use of Cubase Audio, I can honestly say I've lost no more than a few minutes of work. And in the great computing scheme of things, I think that's pretty good going. Steinberg have laid the spectre of Cubase Audio v1.0 well and truly to rest. Who says you never get a second chance in this life?

The essentials...

Prices inc VAT: Cubase Audio v2.0 - £699

Falcon Audio - £699 (with FDI, £1,089)

Audiomedia bundle - £1,449

More from: Harman Audio, (Contact Details)

Hardware - a deck of cards

Digidesign themselves have recently expanded their range considerably, and now offer a variety of systems based around their ProTools, Sound Tools, Audio Media and Session 8 packages. The table below lists the sound cards available and audio channels available through Cubase.

| Card | Audio channels |

|---|---|

| ProTools single card | 4 |

| ProTools multiple cards (with accelerator card) | 8-16 (depending on number of cards) |

| Audiomedia II | 4 |

| Audiomedia LC | 2-4 (depending on computer model) |

| Session 8 | 8 |

| Sound Tools II | 4 |

| Audiomedia I | 4 |

| Sound Tools I | 2 |

Given that Cubase Audio is so inextricably linked to the Digidesign hardware which drives it, distributors Harman UK have taken the not illogical step of bundling it together with an Audiomedia II card at a knock-down price. The combined cost of the individual items wouldn't leave much change out of £2,000. The bundle currently retails at under £1,400.

This isn't quite such good news if you were considering buying the system in separate chunks to spread the cost, using Cubase simply as a MIDI sequencer to begin with. But you pays your money...

Cubase the sequencer: what you need to know

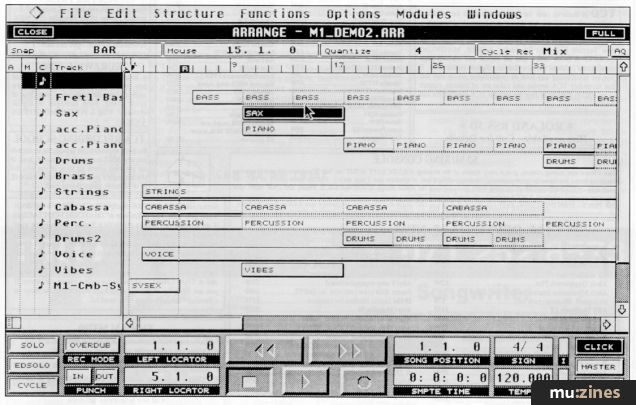

The Arrange page, with Part Inspector open on left-hand side

What set Cubase apart from all other sequencers at the time of its release was its now famous (and much-copied) Arrange page. Though visually providing little more than tracklist, a transport control bar and a large blank space, this actually gives you some clue as to what is possible when arranging a piece of music. Having recorded various musical parts on each of the tracks, you're free to move, copy, extend, cut, join, overlap, or delete these virtually without restriction.

Key Edit mode - often likened to old player-piano technology

Supporting its Arrange page, Cubase provides a series of Edit pages which you choose according to the type of data you wish to edit, and/or the way you prefer to work. Editing conventional music, for example, can be carried out in Key Edit mode, where notes are represented by oblong blocks set on a grid, in line with a graphic representation of a keyboard. The longer the block, the longer the note duration.

The Score Editor opened over the Arrange page - it's possible to have more than one window open at once

Many musicians, however, prefer to view music as conventional notation using notes on staves. This is also possible in Cubase in the Score Edit page, which employs a sophisticated system for converting the notes you enter via keyboard (or any other MIDI instrument) into standard notation.

Music such as rhythm tracks may also be viewed as standard notation and edited in that way, though this is hardly convenient - even for the die-hard muso. Writing or editing a percussion part is best carried out in Drum Edit mode, where a list of percussion instruments (previously defined by you) is set against a grid, upon which appear the notes of each instrument as they occur in the bar.

The List Editor opened over the Arrange page - it might not be very musical, but it gets the job done

Not quite so intuitive, List Edit offers exactly what its name suggests: a straightforward list of MIDI events in chronological order. This too is set against a grid, but here all the objects run from top left to bottom right in the order they occur in the music. And we're not just talking notes: List Edit includes every kind of MIDI event (unless specifically instructed to filter them out), from pitch-bend to modulation.

Finally, Logical Edit offers its own unique kind of editing functions which, though hardly musical, often provide the fastest method of changing MIDI data.

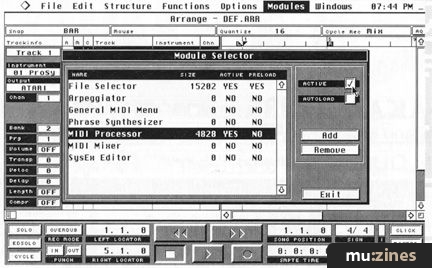

To complement the extensive arrange and editing functions, Cubase sports a number of other major features. Among these is the Interactive Phrase Synthesiser, which takes a portion of your music as its source material and from this generates a series of musical variations, the controlling parameters of which are set by you.

Demonstrating just how far MIDI has come in the past few years, Cubase's MIDI Processor uses simple MIDI triggering to re-create many of the effects of a conventional sound processor such as delay, chorus, and pitch-shifting. Though they can only be applied to MIDI tracks (audio tracks cannot be processed), the effects are quite convincing, and in the case of delays, easier to set up than on a conventional processor, particularly where they are rhythmically linked to a part.

Cubase's remaining major feature is its MIDI Mixer. This is where the software really starts to interface with the equipment which surrounds it, and where the nightmare of setting up and re-setting up your entire system for each song you load in becomes a thing of the past.

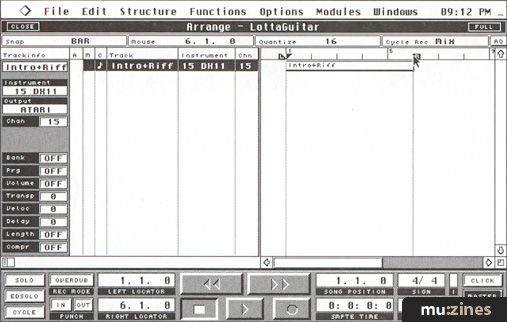

Falcon Audio: the Atari alternative...

MIDI and audio tracks in a seamless and harmonious blend on the Atari Falcon

Unlike any other computer - with the exception of the AV Macs which are more expensive - Atari's Falcon has the in-built ability to support direct-to-disk recording. To capitalise on this, Steinberg have developed a version of Cubase Audio specifically for the Falcon, known (logically enough) as Falcon Audio. However, the raw Falcon out-of-the-box needs a few hardware tweaks before it will give its best (check out the Falcon Hardware Mods feature in our last issue).

The Falcon Audio program is protected with a dongle which plugs into the cartridge port. You also need to plug a CAC (Cubase Audio Clock) into the Falcon's DSP (Digital Signal Processor) port; this lets you record at 44.1kHz, which the Falcon alone cannot do.

Alternatively, and a much better option, you can go for Steinberg's FDI (Falcon Digital Interface) which plugs into the DSP port instead. This has both optical and digital Ins and Outs for connection to a DAT, a sampler or other digital device. If you have a DAT you will probably get better sound quality by recording through it instead of using the Falcon's audio sockets. The FDI does not support DAT's 48kHz rate but, along with support for other sample rates, this has been promised in the next update.

The FDI package includes a utility to convert an .AIF file from stereo to mono and vice versa. It also has a program which lets you stream audio files to and from a DAT recorder - essential for backing up your work.

Cubase Audio will not work with the Falcon's internal IDE drive - you must have an external SCSI hard disk. But again, for serious use you would need more space than the standard internal drive supplies.

Like its Mac counterpart, Falcon Audio has recently been updated to support 16 tracks, and this requires a pretty nippy disk, although power fiends may notice a slight drop in quality if they insist on squeezing all 16 tracks out the door at once. Incidentally, if you are a 16-track person - or even an eight-track person who wants to make the most of their system - check out the FA8 (Falcon Analog 8), a hardware plug-in which provides eight individual audio outputs for £449.

Functionally, Cubase Audio for the Mac and the Falcon are pretty similar. If you see the program running on a fast Mac, the Falcon version can seem a little slow at times although not unbearably so. NVDI, the screen driver, is a help but if you find that speed is a real niggle, you need a Falcon accelerator.

The best thing about Cubase Audio for the Falcon is the fact that you can set up a complete system, including computer, for around £2,500. If you're already a Cubase-on-the-ST user, Cubase Audio will slot into your existing setup and working practices quite seamlessly. Ian Waugh

Also featuring gear in this article

Featuring related gear

Clash of the Titans

(MIC Oct 89)

Cubase 2.0

(SOS Dec 90)

Cubase In-depth

(MIC Jan 90)

Cubase MIDI Mixer - Programming Clinic (Part 1)

(SOS Oct 92)

Cubase MIDI Mixer - Programming Clinic (Part 2)

(SOS Nov 92)

Dream Sequences (Part 1)

(MX Dec 94)

Dream sequences (Part 2)

(MX Jan 95)

Dream Sequences (Part 3)

(MX Feb 95)

Dream sequences (Part 4)

(MX Mar 95)

Dream sequences (Part 5)

(MX Apr 95)

Dream sequences (Part 6)

(MX May 95)

Dream sequences (Part 7)

(MX Jun 95)

Hands On: Steinberg Cubase

(SOS Jan 92)

Steinberg Cubase - Version 3.0 Software

(MT Sep 92)

Steinberg Cubase 3.0 (Part 1)

(SOS Apr 92)

Steinberg Cubase 3.0 (Part 2)

(SOS May 92)

Browse category: Software: Sequencer/DAW > Steinberg

Publisher: The Mix - Music Maker Publications (UK), Future Publishing.

The current copyright owner/s of this content may differ from the originally published copyright notice.

More details on copyright ownership...

Control Room

Review by Nigel Lord, Ian Waugh

Help Support The Things You Love

mu:zines is the result of thousands of hours of effort, and will require many thousands more going forward to reach our goals of getting all this content online.

If you value this resource, you can support this project - it really helps!

Donations for September 2025

Issues donated this month: 0

New issues that have been donated or scanned for us this month.

Funds donated this month: £0.00

All donations and support are gratefully appreciated - thank you.

Magazines Needed - Can You Help?

Do you have any of these magazine issues?

If so, and you can donate, lend or scan them to help complete our archive, please get in touch via the Contribute page - thanks!